10 years of March of Hope: A new beginning?

September 12th, 2025 - written by: migration-control.info

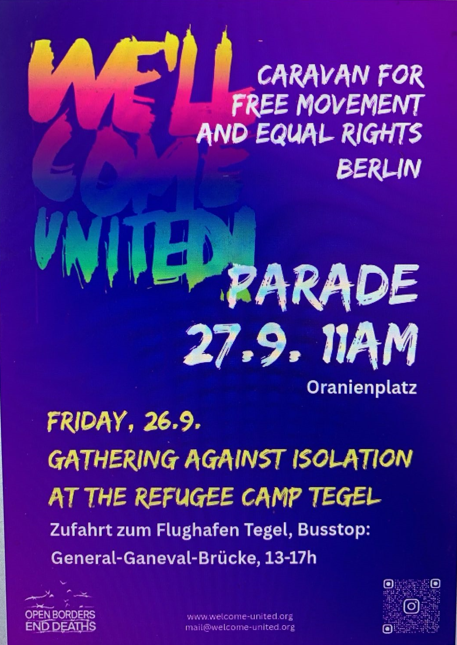

Ten years after the March of Hope in September 2015, we should talk about the possibility of the unexpected. The Chain of Actions for Free Movement planned from Rabbat to Eisenhüttenstadt could be a starting point. So could the solidarity caravan of the We'll Come United movement, which will travel from reception camps in Thuringia via Saxony and Brandenburg to Berlin from 20 September, ending with a large parade through the city on 27 September.

Of course, the setbacks of recent years weigh heavily on us: the brutal violence at the borders, the criminalisation of people on the move, the growing system of isolated camps, the aggressive deportation regime, increasing racist violence on the streets. Our thoughts are with the people who are stuck in unspeakable conditions in Libya and Tunisia, in Sudan and Gaza, and with those who have died - bombed, shot, starved, drowned or died of thirst.

But let us remember: the situation was also dire at the beginning of 2015.

People who had fled Syria and West Asia were stuck in Lebanon and Turkey. Daily food rations had to be reduced because donor countries were skimping. More and more groups and families were wondering: how can we get out of here? No one could predict what would happen in the following summer of migration.

Several factors came together: the unacceptable conditions in the Middle East, the Greek Syriza government, which allowed the migration movement to pass, and the determination of the people, who opened the borders to Macedonia by force of numbers. With the help of local supporters, they were able to make their way through Serbia to Hungary.

The story of that summer has been described many times. The authorities in the Balkan states set up a formalised corridor to maintain at least formal control.

In Hungary, Victor Orban proposed at the time to stop the movement and send them to camps. Thousands were stranded at Keleti railway station in Budapest. On 3 September, they began their "March of Hope" on the motorway towards Austria. The Merkel government wanted to avoid a bloodbath and opened the borders. The refugees were able to travel freely through Europe by train; the Dublin system was thrown into disarray.

Initiatives and projects for a “Willkommensgesellschaft” (literaly “welcoming society”) sprang up all over Europe, with 8 million people involved in Germany alone. Numerous anti-racist projects flourished. In several cities, for example, there was the "Solidarity City" initiative, which aimed to open up urban society and infrastructure to everyone, or the "Citizens' Asylum" to protect people from deportation. And with We'll Come United, the idea arose to anchor the self-organised power of refugees in the shelters and carry it onto the streets with large parades.

A new beginning and repression after 2015

Of course, the reaction followed swiftly: authorities sealed the border at Idomeni, struck the 2016 EU-Turkey deal, launched the so-called hotspot system, built the Moria camp, outsourced border protection to the African continent, and shut down Italy’s search and rescue programme in the central Mediterranean — a move that has cost thousands of lives. A dogma of deterrence was enforced: The EU and its member states went on to fund and train new "coast guards" to intercept and abduct people on Europe’s behalf, armed Frontex to support these operations, and signed memoranda of understanding to formalise the entire system. Meanwhile, they criminalised civilian search and rescue, expanded the camp system, and institutionalised pushbacks, torture, forced labour, and chain deportations.

Today, across Europe, we see racist ideas and policies being fuelled and put into action against the backdrop of a global rise in authoritarian capitalism.

But that is only one side of the coin. On the other side, "a true continent of practical solidarity on a small scale" (C. Jakob) has emerged, with numerous groups supporting refugees and migrants in North Africa, on their journey across the sea, upon arrival, on their way through the bureaucratic landscape and in enforcing their right to stay. Today, we live in a "post-migrant" society of many. This is not least our legacy from 2015, and we want to build on it.

When we talk about 2015 today, we should be aware of our strengths: in many places and cities, our practical solidarity on a small scale is stronger than the racist manoeuvres of politics. And there are self-organised migrant groups that organise themselves across the Mediterranean, beyond the borders of Europe.

Count on the unexpected

Ten years after the March of Hope, we want to try to revive and show our practical solidarity on the streets as well. Can we achieve a turning point in the summer of 2025?

Let's think back not 10, but 20 years, to the grim 1990s and 2000s. Back then, too, setbacks occurred everywhere: the arson attacks in Rostock and Hattingen, or the massive tightening of asylum laws. The breakthrough of 2015 came as a surprise to everyone — to think tanks, to Frontex, to politicians.

Today, the number of people who make it to Europe despite all the fences, barriers and deterrents is as high each month as it was in the entire year in the 2000s. Many are organising themselves and have become part of a society based on solidarity, anti-racist resistance and activism. More and more people are growing fed up with the current authoritarian trend and feel that it is time to take to the streets again. We must shift the atmosphere, make our initiatives in the districts and neighborhoods visible, and show that we are here to stay.