Between the Necessity and the Ban on Migration: an Assessment of Senegal's (Im)Mobility Policies in 2023

March 26th, 2024 - written by: Ibrahima Konate

This article describes the obstacles to mobility and the violations of the rights of migrants in Senegal in 2023. The domestic political context is marked by a sharp regression of democracy and the murderous repression of demonstrations. This text has been drafted at a time of increasing human rights violations in Senegal: rights linked to migration — such as the right to free movement within the member countries of the Economic Community of West African States — but also the right to information and the right to demonstrate. These serious infringements of fundamental rights represent a danger for the whole of Senegalese society and jeopardises the country's future development.

Introduction

For the past twenty years, the freedom of movement of citizens has been flouted by increasingly repressive policies imposed on the State of Senegal by the European Union (EU). The clear aim is to prevent so-called "irregular" migration to Europe and to stop mobility at its roots by keeping African nationals in their countries of origin. Various measures have been put in place to externalise the European borders and combat any desire to leave.

Perhaps the most visible of all these mechanisms, is Operation Hera, a naval management tool for migratory flows launched in 2006. Coordinated by Frontex, the European border and coastguard agency, Hera intercepts migrant pirogues and sometimes pushes them back to the African coast. Although the Hera ceased operating in 2019, the Spanish vessel is still present in Senegalese waters. In addition there are many projects financed by the NDICI (Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument) and the EUTF (EU Emergency Trust Fund for stability and addressing root causes of irregular migration, launched in 2015). Their aim: to prevent desires and dissuade attempts to leave.

2023 was particularly harsh for the Senegalese people. Domestically, demonstrations in support of the Pastef opposition party led by Ousmane Sonko, who was imprisoned in July 2023, were violently repressed by the security forces. At least 29 people were killed during the June demonstrations, and nearly a thousand were arbitrarily arrested without trial. Never before in Senegal's recent history have the people suffered such attacks on their right to demonstrate or express themselves. In addition to individual freedoms, the entire democratic system has been undermined.

At the same time, in 2023 the sad record of the number of people who died in migration while trying to reach the Canary Islands from the Senegalese coast was broken.[1] The Atlantic area between West Africa and the Spanish archipelago has become the deadliest migratory route in the world, with 6,007 deaths according to an estimate by the NGO Caminando Fronteras. This morbid situation is the direct consequence of the intensification of restrictive migration policies, which further hamper access to visas for most African nationals. De facto they are excluded from access to so-called legal mobility.

Given the worsening situation, it is important to analyse this reality, which is often misappropriated and exploited for political ends, so as not to draw the wrong conclusions. Based on field data collected through contact with those affected at the crossroads of migration routes and as part of my activism alongside the Boza Fii association as well as part of my personal research, I present an analysis of the consequences of migration policies on the fundamental rights of Senegalese people to migrate.

When migration becomes a necessity

What is often presented as a choice in the official discourse of governments and institutions is in reality not a choice: nobody chooses to risk their life to migrate. If people do, it is because they have no alternative but to put themselves at risk to regain the freedom that has been taken from them. If Senegalese people take these risks, it is because they are denied access to travel authorisations (visas), while Europeans are free to come to our continent at their convenience. If the Senegalese embark on pirogues to the Canaries, it's also because their country's resources are being plundered by outside economic actors.

Senegal's fishing workforce, which represents more than 17% of the working population, are facing a constant shortage of resources. This shortage of fish is exacerbating the precarious situation of all those working in the fishing industry, who are finding it increasingly difficult to make a living. Yet the fishing agreement with the EU continues to be renewed. Fishing licences are still being granted to Chinese vessels (poorly disguised as Senegalese vessels) and no real action is being taken against foreign trawlers, particularly Russian ones, which are illegally plundering Senegalese waters. This illustrates, in the same way as the grabbing of agricultural land and the exploitation of oil deposits,[2] the dispossession of Senegal's resources to the detriment of its people and for the benefit of multinational companies. This ist just as devastating on a human level as it is economically and ecologically.

More often than not, these factors are not mentioned in the dominant political discourse on migration. However, they are crucial to understanding the impasse in which Senegalese people find themselves when they want to emigrate because they have no prospects at home.

The Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 and the war in Ukraine in 2022, dealt severe blows to the economy, fanning inflation and with it impoverishment. As if caught in a trap, the Senegalese population, who had previously made their living from fishing, farming or the informal sector now face an impossible dilemma between fighting to survive locally or leaving risking their lives in the hope of new horizons.

The gap between Senegal's wealthy few and the rest of the population continues to widen. There is a glaring development inequality between urban and rural areas. Unsurprisingly, young people and women are affected the most by this situation.

The democratic crisis, a new reason to leave

In the course of 2023, the new impetus offered to young Senegalese by Ousmane Sonko and the wind of hope accompanying his anti-corruption, anti-colonial rhetoric gradually faded, when the opposition leader was imprisoned, his party dissolved and his candidacy for the presidential election of 25 February 2024 invalidated. While the motivation of the opposition movement remained intact, the vigour of the opposition was diminished by 2023 due to the government’s repression.

However, the latest events of March 2024 mark a turning point: Ousmane Sonko and his replacement candidate, Bassirou Diomaye Faye, have been released from prison. If the election, which has been postponed until 24 March 2024, goes well, Sonko has a real chance of winning.

Whatever happens in the future, the increase of the number of Senegalese leaving the country through so-called irregular channels in 2023, is inextricably linked to the country's overall situation, which is threatened by instability. The economic, social and political crisis, the violation of fundamental human rights, the tightening of access to visas, fishing agreements and licences, etc. are all factors fueling general discontent.

The authorities are repressing the opposition, the media and civil society. President Macky Sall's promise to organise a fair election is in total contradiction with the fact that the authorities have filled the prisons with hundreds of political opponents over the past three years. Many people have been imprisoned for simple critical posts on social networks.

Despite the many resources used by the Senegalese authorities to intimidate the demonstrators, Senegal's youth continues to organise and voice their dissent. Nonetheless, for many young people, the intensification of political repression has become yet another reason to leave the country. The period since Ousmane Sonko was sentenced to two years' imprisonment in the beginning of June has seen a sharp rise in the number of migrants leaving Senegal.

A young Senegalese man aged 15, placed in a centre for unaccompanied minors after arriving in the Canaries in a pirogue alongside more than 200 other people, told us in October 2023: "I made this sacrifice to save myself, to go to a place where I could live without fear [...]. After ten days at sea, without eating anything during the journey, I saw death up close because some of my companions didn't survive. All to escape the tyrannical madness in Senegal."[3]

And this is just one case among thousands. In 2023, the Atlantic route was the scene of terrible tragedies and increasingly serious human rights abuses. On this route, which links the coasts of West Africa to the Canary Islands, tens of thousands of people departed in 2023 alone.

Among those who managed to arrive safely on the Canary Islands (Spain) were men as well as women, minors and even babies. Women and minors are exposed to even more violence.

Record figures despite thousands of interceptions

Capsized boat at Gandiol, 2023 (c) Ibrahima Konate

In Senegal, the Boza Fii association has recorded more than 270 pirogues leaving the Senegalese coast heading to the Canary Islands between June and December 2023 alone. The coastal departure points vary: around Dakar (from Yarakh to Thiaroye, via Bargny and Rufisque), the northern coast (Gandiol, Saint-Louis, Cayar, Fass Boye), the south of Dakar (Mbour, Joal, Djiffer, the Saloum islands) and even Casamance (Kafountine). Data collected by Boza Fii suggests that the bulk of the departures began in mid-June, with more than 210 pirogues between June and December carrying 24,256 people, the majority of them from Senegal. These people arrived on the various islands of the Canary Islands, distributed as follows:

- Tenerife: 6,967 men, 391 women, 455 minors, 43 babies and 43 corpses, a total of 7,899 migrants.

- El Hierro: 12,564 men, 458 women, 447 minors, 20 babies and 8 corpses, making a total of 13,497 migrants.

- Gran Canaria: 2,719 men, 75 women, 15 minors, 1 baby and 14 corpses, making a total of 2,824 migrants.

- Gomera: 36 men.

The period from June to November 2023 is reminiscent of the "cayuco crisis" (the Spanish name given to the pirogues used for crossings) between 2006 and 2009. However, the figures in 2023 exceed those of that period. Last year, according to the Spanish Ministry of the Interior, 39,910 people managed to reach the Canary Islands from the West African coast.

This number could have been even higher had the Senegalese Navy not intercepted 9,141 would-be emigrants in the last seven months of the year.

It should also be noted that on 20 August 2023, 184 Senegalese people were intercepted by the Spanish Guardia Civil off the coast of Mauritania, and handed over to the Senegalese navy after spending a few days on the Spanish patrol boat. According to the NGO Boza Fii, the DNLT (Division de lutte contre le trafic de migrants et pratiques assimilées, a unit of the Senegalese air and border police) has identified 8 of these migrants, who are now being prosecuted for criminal conspiracy, complicity in smuggling migrants by sea and endangering the lives of others.[4]

Guardia Civil at Gandiol, 2023 (c) Ibrahima Konate

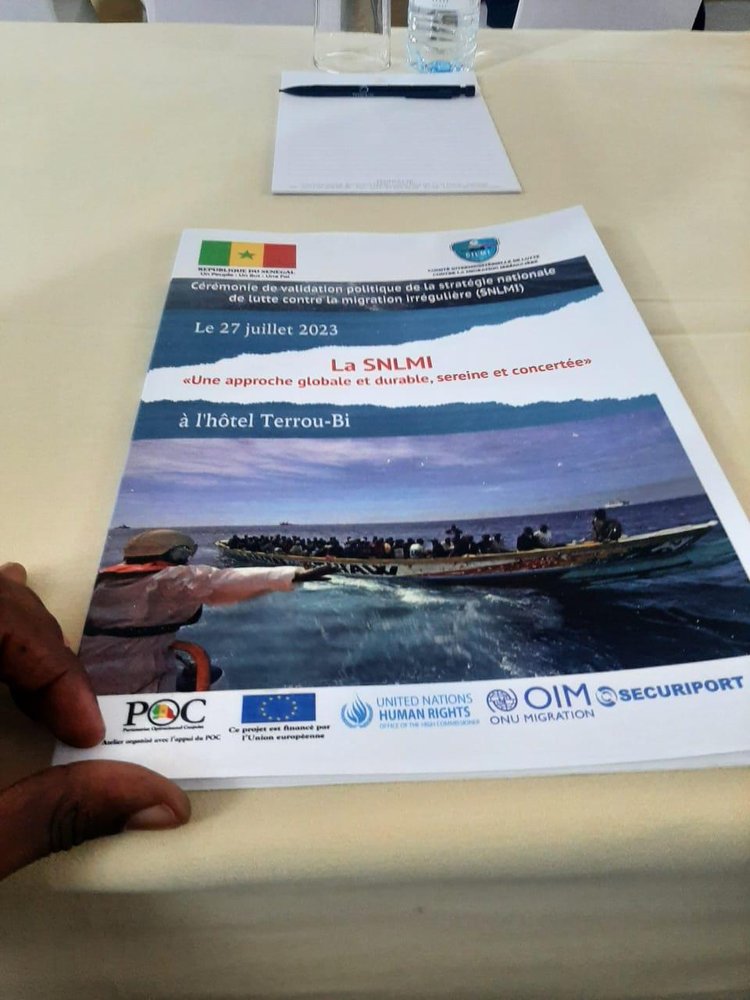

Reinforcement of the repressive framework: In recent years, border controls have been considerably strengthened in West Africa, with the deployment of coastguards and the introduction of cutting-edge technology and automated information systems (e.g. the MIDAS system),[5] which has been installed in Mali, Guinea Conakry, Burkina Faso and Niger. This tougher approach is fueling the debate in civil society on the issue of people's right to mobility. Under pressure of the European Union, the Senegalese government set up a dedicated body in 2020: the Interministerial Committee to Combat Irregular Migration (CILMI). Its work, and that of the Division for Combating the Smuggling of Migrants and Related Practices (DNLT, created in 2018), is increasingly criticised by civil society. On 27 July 2023 in Dakar, in the salons of the luxurious Terrou-Bi hotel, Prime Minister Amadou Ba validated Senegal's "National Strategy to Combat Irregular Migration”. He presented a comprehensive action plan covering various public policies. On 4th of August, in the midst of a political crisis following the latest arrest of Ousmane Sonko, the European Union and the Senegalese government inaugurated the new headquarters of the Senegalese DPAF (Division de la police de l'air et des frontières), which was financed by the EU with 9 million euros.

Thousands dead

In Senegal, the year 2023 was tragically marked by the deaths of several thousand emigrants who lost their lives trying to reach the Spanish coast on board of cayucos. Between June and December alone, more than 3,176 people died on the "Canaries route" from Senegal, more than half of the 6,007 victims who left from the coasts of West Africa more generally.

The summer constituted a series of tragedies. For example, at the end of June, a pirogue that had set off from Kafountine with some 200 people on board disappeared in the open sea. On 12 July, another boat boat capsized near Saint-Louis, killing at least 8 people. On 24 July, a pirogue capsized off Ouakam beach in Dakar. According to several corroborating accounts, it was being pursued by a maritime patrol when it hit rocks. The shipwreck caused at least 16 deaths. On 14 August, a pirogue was found 277 km from the island of Sal, in the Cape Verde archipelago. Its destination was the Canaries, but when its engine broke down, it drifted for weeks. Having exhausted their food and water supplies, the passengers went through hell. Only 38 people survived, while 63 died.

Public opinion in Senegal has been deeply moved by these tragedies, which have been widely reported in the national and international press.

But it is necessary to look at the trend starting in 2020, the year in which departures began to increase, after a "quieter" decade on the Atlantic route.[6] According to the NGO Caminando Fronteras, 1,851 people died (or disappeared) in 2020, as they attempted to cross to the Canary Islands from the West African coast. A total of 2,170 people died, trying to get to Spain that year: an increase of 143% compared to 2019. This provoked a protest movement in the Senegalese society, which manifested itself first on social networks and then on the streets.

At the end of October 2020, around 480 people disappeared on the sea in a series of shipwrecks within a week. In response the "Collectif 480" was formed by various Senegalese movements (Y en a marre, Doyna, Frapp, France Dégage). The aim of the collective is to highlight the responsibility of governments for these tragedies: the shipwrecks are the direct consequence of the intensification of the repression of migration by the Senegalese and European (particularly Spanish) authorities, combined with the granting of new fishing licences to foreign industrial vessels, at a time when small-scale fishing is already in dire straits.

Importing anti-migration concepts

In the eyes of civil society engaging in this issue, Senegalese politicians are far too silent on the subject of border victims. Even worse, the Western vocabulary criminalising migrants has been imported to Senegal. Terms as "clandestine migrants" and "irregular migration” further reinforce the artificial opposition between migrants perceived as legitimate and others who are considered illegitimate, or even criminal.

International organisations also introduced the strange concept of "potential migrants", which refers to people who are likely to want to migrate and who should therefore be immobilised in their region of origin. The term "potential migrants" is used mainly in anti-migration campaigns run by international organisations such as the IOM[7] (International Organisation for Migration). Instead of tackling the structural (economic and political) causes of migration, they emphasise the risks and dangers of the migration process, with the aim of discouraging departures. The result is that migrants and their families are being accused and stigmatised.

The terms and concepts that criminalise migration, collide with long-standing societal norms. In Senegal, migration and the right to move have historically been part of the national culture. Migration has long been socially valued, there is a Wolof proverb that says: Ku dul tukki do xam fu dëkk nexee ("He who has not travelled does not know where it is good to live").

The vocabulary that criminalises migration and the associated practices of preventing migration also contradict the legal standards of ECOWAS (Community of West African States), which guarantee freedom of movement within the Community area for all nationals of the member states. All this also violates Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UN, 1948), which states that "everyone has the right to leave any country, including their own".

Emigration criminalised: In Senegalese civil society, many players highlight that the 2005 law,[8] which makes it a criminal offence to leave the country “illegally”, marked a turning point for people on the move. Supposedly intended to combat migrant smuggling, it criminalises so-called irregular emigration from Senegalese territory, through Article 4: "Clandestine migration organised by land, sea or air is punishable by 5 to 10 years' imprisonment and a fine of 1,000,000 to 5,000,000 CFA francs, whether the national territory is used as an area of origin, transit or destination."[9]

What can we expect from the 2024 presidential election?

Initially scheduled for 24 February, the 2024 presidential election was suspended indefinitely by President Macky Sall on the eve of the opening of the electoral campaign. The National Assembly then postponed the poll until 15 December, but the Constitutional Council overruled the postponement. In the end, the election will likely take place on Sunday 24 March. After the elections, Senegal will have to deal with major issues in terms of respect for fundamental and economic rights.

We can only regret that of the 19 candidates officially in the running, not one is speaking out on the issue of migration and the violations of the rights of migrants. This silence leads us to fear the repetition of a migration policy similar to that pursued under Macky Sall, which is in line with European interests: a repressive policy that violates human rights.[10]

As far as we know, of all the parties in the presidential race, only Ousmane Sonko's Pastef has openly supported freedom of movement. But words alone are not enough: if the Pastef candidate Bassirou Diomaye Faye comes to power, concrete action will have to be taken.[11]

Conclusion

Following in the footsteps of the IOM and the European Union, a number of Senegalese civil society players have made the fight against so-called "irregular" migration part of their agenda. At the state level, Macky Sall's government repeatedly announced that it will strengthen existing measures in this area. These speeches and positions serve security policy and racist political objectives.

In Europe, migration is no longer treated as a humanitarian emergency, but as a security threat, used to justify the unjustifiable. It's not just "illegal migration" that is targeted, it's the migrants themselves who are criminalised, along with the solidarity movements that support them. In reality, they are criticised not so much for what they do (migrate), but for who they are (African, black people). The image of the black migrant is central to the myth of invasion, imagined and feared by European governments. The racist nature of this thinking needs no further proof: the glaring difference between the welcome given to Ukrainian refugees and that refused to exiles from the Middle East and Africa is a clear demonstration of this.

Labelled as serious criminals, African migrants are relegated to the rank of "undesirables" with limited rights, whose lives can be sacrificed. No, it's not borders that kill people, but the states that are behind them: militarisation, biometric data collection, infrared detection, drones, the supply of lethal weapons to coastguards and the raising of barriers. Border areas have become war zones — a war declared by the European Union.

The stakes are high for the future Senegalese government, which will be elected by the people in the coming weeks. Because even if there is a lot of blame to be directed at Europe, it is important to remember that African states, especially Senegal, participate in the criminal enterprise in various ways. For example by refusing to effectively search for people who have died or disappeared during migration, they are violating their most fundamental obligations. When it comes to migration, a radical change of approach is essential.

If justice is to be done, official investigations must be carried out internally into the violence committed over the last three years. The amnesty law passed on 6 March 2024, which admittedly allowed the release of people arbitrarily detained, must be repealed so that those responsible for the murder of protestors can be held accountable. Freedom of expression, association, assembly and peaceful demonstration must be restored, and free and fair elections must be guaranteed in the future.

Of course work must be done to ensure that everyone has access to essential goods and services, but also to guarantee the free movement of people and their goods within the ECOWAS zone.

All these challenges must be overcome, if Senegal is to ensure that the rights of its people are respected.

A few words about the author

Ibrahima Konate is an activist and independent researcher whose work focuses on migration from Africa to Europe. He is a member of the international Alarm Phone network, of which he is one of the representatives in Senegal. From 2020 to 2024, he was secretary of the Senegalese association Boza Fii. Ibrahima Konate's activist research focuses on the European Union's border externalisation policies and their consequences for Senegalese nationals' access to international mobility. These subjects relate in particular to the deployment of Frontex in Senegal, and more generally to bilateral agreements between EU Member States and African states aimed at restricting people's mobility. Ibrahima Konate's work seeks to highlight the challenges faced by migrants, with the ambition of reflecting on alternatives capable of bringing positive changes in migration policies, which are currently aimed primarily at hindering the movement of individuals from Africa to Europe.

Acknowledgement

This text was drafted with financial support from the Heinrich Böll Foundation Senegal. The text was jointly edited by migration.control-info and the Heinrich Böll Foundation Senegal.

Footnotes

-

Not to mention all the people who have died or disappeared on other migratory routes.

↩ -

The start-up of Senegal's first oil and gas fields in 2023 has once again been postponed. The GTA (Grand Tortue Ahmeyim) gas field, located offshore on the Mauritania-Senegal border, is due to come on stream in 2024. Several companies have won contracts to exploit these gas resources: the British company BP (61%), the American company Kosmos Energy (29%), in partnership with the Senegalese state-owned company Petrosen and the Mauritanian company SMHPM (10%). The Sangomar field (around 90 km off the Senegalese coast, above the Gambian border) is also due to come on stream in 2024. This offshore field contains both gas and oil. It is 82% owned by Australian company Woodside Energy and 18% by Senegalese company Petrosen.

↩ -

Telephone interview with a minor who arrived in the Canary Islands on 21 October 2023 and was placed in the El Hierro centre for unaccompanied minors.

↩ -

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) questioned the arbitrary detention by the Spanish authorities of migrants accused of being boat captains. This was claimed in 2022 in a report, devoted to the trafficking of migrants on the Canaries route. The report acknowledged that in many cases, the "captains" who took charge of sailing the boat had no connection to smuggling networks. They were simply people who had set off, like the others, on the migration route. For more information, see UNODC, "Northwest African (Atlantic) Route - Migrant Smuggling from the Northwest African coast to the Canary Islands (Spain)", 2022.

↩ -

Système d'information et d'analyse des flux migratoires (French acronym: SIAFM; English acronym: MIDAS). This is a border management information system (FMIS) developed since 2009 by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM). According to the IOM, it is "capable of collecting, processing, storing and analysing traveller information in real time and across an entire network of borders". MIDAS "enables states to control those entering or leaving their territories more effectively, while also providing a reliable statistical basis for their migration policies". In 2017 Dakar international airport was equipped with the E-Gates automated control system, linked to Interpol's files.

↩ -

If the Canaries route has been reactivated, it is mainly because of the increasing difficulty of passing through Libya (the central Mediterranean route), Turkey and Greece (the Aegean route) or the Straits of Gibraltar. For a better understanding of these route changes, read CQFD, "Sénégal, les pirogues de la dernière chance", April 2021.

↩ -

Example of a text in which the term "potential migrants" is used repeatedly: IOM, "Impact evaluation report: Migrants as Messengers (MaM) campaign - The impact of peer-to-peer communication on potential migrants in Senegal", 2019.

↩ -

Law no. 2005-06 of 10 May 2005 on the fight against human trafficking and similar practices and the protection of victims.

↩ -

Law 2005-06, Chapter II, article 4. This law was added to Senegalese criminal law in order to institutionalize the provisions of the United Nations Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air of 15 November 2000.

↩ -

In his speech on 8 November 2023, for example, Macky Sall said he wanted to "neutralise" the departure of migrants from Senegal.

↩ -

Diomaye Faye was elected as the new president on 25 March. "Thousands of people poured onto the streets to celebrate.Children cheered on their parents' shoulders, others hung out of car windows with flags around their shoulders and shouted: "We are free! Senegal is free!" In front of the Pastef headquarters, people danced with brooms to symbolise the elimination of corruption."

It now remains to be seen whether the new government will manage to defend the interests of the Senegalese people against the interests of the EU.

↩