Sudan: From Revolution to NGO Governance

December 13th, 2025 - written by: HoA Media Office

This translation was supported by our friends of the Free Sudan Gazette

War Disaster: Killing, Displacement, and Starvation

The war in Sudan, similar to that in Gaza, is a prototype of the New Wars which are directed against populations. As Alex de Waal has recently argued, there is a Return of the Starvation Weapon worldwide, and large parts of the population have been cut off from food aid.

What is that war about? This is not just a war between two generals. This war started as a war of counter-revolution in the first place, and it has been developed into an economy of starvation, extraction, and displacement.

The war is now deemed responsible for the deaths of up to 150,000 people in mass casualty incidents, and of more than 500,000 people due to hunger. There are 11,8 million people displaced, and millions under threat of starvation. While both of the warring parties, and the militias associated with them, have committed war crimes, it is obvious that the RSF, drawing on their Darfur experience, and the Emirates in the background, have developed a system to make profit from disaster.

Apart from the Red Sea Hills in the East, the Marra Mountains in the West, and the Nuba Mountains in the South, Sudan is a flat country. This explains why it was quite easy for the RSF to call for mercenaries from the Sahel and to swiftly advance into the centre of Sudan with their technicals in the first year of the war. The army (SAF) had no infantry, they dropped bombs. Khartoum and Omdurman were bombed by the SAF, and looted by the RSF. Lorries full of looted belongings moved westwards.

In March 2025, the SAF was able to re-conquer the triangle capital and the Eastern and Central regions of Sudan. The SAF received new weapons from Turkey, Egypt, and Iran, and activated Islamist militias, the latter being a nasty curse for the future. The RSF was continuously supported by the UAE, which delivered arms, drones, and Columbian mercenaries to them, in exchange mainly for gold, but also for future profits from displacement.

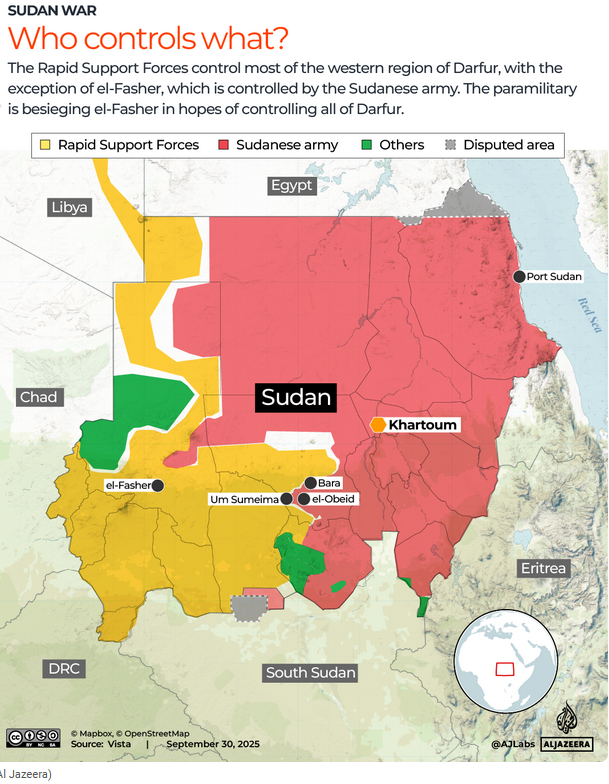

The timeline of the war can be followed on the Sudan War Monitor. At the moment, the war has two main theatres: Kordofan, with changing frontlines in the region of El Obeid, and with ongoing massacres and displacements, and Darfur, where the RSF has recently captured El Fasher (26.10.2025) and thus won definite supremacy in the North Darfur state. During the preceding months, a large influx of new weapons came from the Emirates, via Haftar’s Libya. Since summer 2025, the RSF is in control of the border region to Libya, which will give them weight in future negotiations with the EU.

In Kordofan, the SPLA-(N) has allied with the RSF and is attacking from the Nuba Mountais. Their leader is meanwhile the vice president of a parallel government, under the presidency of Hemedti. As the two sides vie for more power in the area, more civilians are being killed in what rights groups say is the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

The massacre in El Geneina in April 2023 was an indication of the direction in which the war in Darfur was likely to develop. Near El Fasher, the capital of North Darfur, there were huge refugee camps dating back to the genocidal wars in Darfur in the early 2000s. The largest of these camps, Zamzan, was converted into a military camp and artillery base by the RSF in April 2025, while hundreds of thousands of civilians were forced to flee and suffered countless abuses. But this was only the prelude. The capture of El Fasher has been accompanied with mass killings and war crimes. Not only soldiers, but also patients and disabled persons in the last existing hospital, the medical staff, and members of the Emergency Response Rooms (ERRs) were deliberately killed, and women raped and mistreated.

For many of the displaced people there is no chance to resettle. The current war is a continuation of the Darfur war, but this time with an explicit capitalisation perspective. The Emirates and their militia leader pursue a project of land grabbing through displacement. The Massalit must be driven from their fields, the Fur from their mango orchards, the Zaghawa and Berti from their extensive economies. The winner takes it all and establishes plantations or cattle ranches on the land formerly held by peasants and herders. This project will certainly be easier to realise in a Darfur warlord state separated from Sudan. In the end, UAE is not only winning gold, minerals, and land, but also takes profit from the humanitarian logistics, feeding the displaced populations in the camps which will be address further down.

Humanitarianism, Intervention, and Logistics

In the Western parts of Sudan, the lack of food is the most pressing problem for the internally displaced persons (IDPs). The violent expulsions and looting by the RSF have meant that agriculture can no longer be practised in these areas in the third season. The land is totally dependent on rain fed irrigation. The World Food Programm (WFP), International Red Cross, and Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) are trying to bring in some food, but convoys regularly come under fire from the RSF. By creating scarcity they want to drive the population into camps. There are other needs connected to medical aid, especially the areas under the control of the RSF. For them however, the population is a burden without a future and an obstacle for making profit.

Since November 2024, more than 2 million IDPs have resettlered in Central Sudan, especially in the states Gezira, Khartoum, Sennar, and White Nile. There are many Emergency Response Rooms (ERRs) working for community kitchens, health, and education. But there are restrictions on the ERRs volunteers., like compulsory registration. Aid shipments are deliberately being held up by the SAF-government for alleged security reasons.

Official aid for Sudan is severely underfunded. OCHA has allocated US$4 billion for the Sudan Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan 2025, of which only 26% has been covered. The largest donors are the US and the EU, while the Emirates are only contributing a small amount of $9 million. The funds from the German government and the EU mainly go to large organisations such as the WFP, FAO or the UN Children's Fund. Funds also go to the IOM, because "Better Migration Management" (BMM) is also continuing also in times of war and keeping refugees stay put is central for the donors. Grass-root organisations cannot receive government grants; only occasionally do informal supplies reach the ERRs via the large agencies. As far as we know, the ERRs only got 1,5 m Euros from Diakonie so far, apart from donations from the diaspora.

So what we see in Sudan at the moment is a combination of deliberate displacement and starvation on the territory which is controlled by RSF, and on the side of SAF a combination of securitarization of humanitarian aid, in combination with restrictions on the ERRs and an Islamist resurgence. Both sides are establishing their own regime to bury the revolution.

A Note on Gaza

We briefly pause here to return to the topic of warfare against populations. Israel's architecture of occupation has been a warning sign for decades; Gaza is now a deeper testing ground. In the war against Hamas, the number of civilian deaths, which were accepted in the “Where-is-Daddy”-programme, initially skyrocketed. This was followed by the displacement of the population from one "safe zone" to the next. The US supplied bombs and humanitarian aid. Then came a period of systematic starvation . Added to this was the indiscriminate hunting of people on the streets with drones. We have regularly documented all these developments in our Monthly Press Review.

The summer of 2025 brought new developments: the Gaza Riviera plan was bluntly about repurposing the territory and expelling the population. Food distribution was accompanied by mass shootings of palestinians. Concepts for resettling the population are currently being discussed: in Israel-controlled camps called "Alternative Safe Communities".

Israel and the Emirates are the most aggressive players in the reshaping of West Asia. They pursue common interests not only with regard to their "military-industrial backbone of normalisation," but also with regard to control of civilian populations. Palantir not only serves Israel to control and target populations in Gaza and the Westbanks, but has also established a joint venture with the UAE, involving "secure, sovereign and high-impact AI applications" – not least to control the millions of imported workers. A key difference, of course, is that Israel kills directly, while the Emirates pursue their population policy by proxy.

Humanitarian Warfare and Logistics

Generally, emergency aid since the end of the Cold War is characterized by the growing gap between the large aid organisations and local aid requirements, the increasing involvement of humanitarianism in military interventions, and last but not least the omission of emergency aid and the staging of wars as population policy. Emergency aid had increased continuously until 2023 but no more so in recent years and it is currently declining.

Let us go back to the end of the Cold War, in order to understand these things better. Michael Barnet, in his book Empire of Humanity. A History of Humanitarianism (2011), has described the situation in the 1990s, shortly after the Cold War, with a striking similarity to the present times. He describes that a

simultaneous decline of the state‘s ability to provide security or perform basic governance tasks and the rise of paramilitary organizations led to wars with no „fronts“, engulfing cities, towns, and villages. Civilians were no longer a tragic consequence of war but rather war‘s intended targets. (p.161)

In this situation, the UN Agenda for Peace shifted towards an Agenda of Humanitarian Intervention. Beginning in 1991, with the response to the plight of the Kurds after the First Gulf War, „Safe Havens“ came up as a concept of intervention. One year later, the response to the famine in Somalia triggered military protection for humanitarian operations („Shoot to Feed“). “State-building” now became a humanitarian goal, addressing „Failed States“ as the „root causes“ of human suffering.

While one of the root causes of states failing was not addressed in Barnet’s book, namely the Washington Consensus and the conditionality of loans, which forced the states to reduce welfare expenses, the results of these politics are well described:

States began shredding their welfare „burden“. The state now claimed that basic protections were properly the purview of, and more efficiently delivered by, NGOs, faith-based agencies, and even a private sector. (p.165)

The contribution of NGOs to global governance is a topic that we cannot fully address in this context. As Gregory Mann has described, aid organisations such as WFP, USAID, MSF and Save the Children established their own form of NGO governance in the Sahel states as early as the 1970s. In an interview with Roape, Mark Duffield has talked about his observations how NGOs came to Sudan in the 1980s:

In reference to Conrad's "Heart of Darkness", the sudden increase in the number of NGOs operating in northern Sudan as a result of the drought in the mid-1980s was aptly described as a "fantastic invasion". At the same time, Sudan quickly became Oxfam's largest foreign aid programme. When capital and labour collide on a global scale, the "fantastic invasion" was part of a profound change in the nature of this confrontation.

Arundhati Roy wrote (cited here from Dinyar Godrej, 2014):

Armed with their billions, these NGOs have waded into the world, turning potential revolutionaries into salaried activists, funding artists, intellectuals and filmmakers, gently luring them away from radical confrontation.

In another text (2014), Roy speaks of the "NGO-isation of Resistance", and she wrote:

The capital available to NGOs plays the same role in alternative politics as the speculative capital that flows in and out of the economies of poor countries. It begins to dictate the agenda. It turns confrontation into negotiation. It depoliticizes resistance. It interferes with local peoples’ movements that have traditionally been self-reliant. NGOs have funds that can employ local people who might otherwise be activists in resistance movements, but now can feel they are doing some immediate, creative good (and earning a living while they’re at it).

Follow the money. We are fairly certain that it is impossible to analyse the role of NGOs in the age of neoliberalism without analysing their finances and the financialisation of their activities. This task still needs to be done.

Returning to the 1990s, the UN was an indifferent bystander during the genocide in Rwanda in 1994 but this was different in Europe. The wars in former Yugoslavia triggered new developments towards humanitarian interventions. In Bosnia, in 1992, the concept of “Save Havens” was resumed, and UNHCR coordinated more then 250 agencies in order to deliver aid and at the same time keeping away the refugees from Western Europe (“Containment through Charity”). In March 1999, after the NATO air strikes on Belgrade had been answered by the Serbian regime with a wave of ethnic cleansing, NATO, side to side with UNHCR, took control over the organization of relief, militarizing the refugee camps, and turning the whole humanitarian business into “humanitarian warriors”.

The same concepts were also used for the US invasions in Afghanistan (2001 – 2021), and Irak (2003). In the “War on Terror”, Humanitarianism became part of the US military strategy. At that time, UAE stepped in. The Emirs did not only send their fighter jets to Afghanistan but also opened their International Humanitarian City as a logistic hub. Today, this district is home to the UNHCR’s global stockpile and an important location of the World Food Programme.

In this context, one could speak of a "logistic turn" in humanitarianism. In his remarkable essay, Rafeef Ziadah has analysed the connection between humanitarian logistics, commercial interests and military projections, using the example of the Emirates. He does not forget to mention that migrant work, under the strong surveillance in a police state, is an essential factor for both humanitarian and military logistics. Ziahad has summarized his findings in an article in MERP, stating that

Rather than reading military intervention separately from so-called humanitarian agendas, it is essential to trace the symbiotic relationship between humanitarian, commercial and military logistics.

In addition, there is a trend towards "Artificial Humanitarianism", which links the humanitarian sector with a network of commercial companies with the aim of digitising processes from the registration of refugees to the delivery of aid supplies. This also involves "predictive humanitarianism", which completely decouples potential aid deliveries from local demand. Here, too, the Emirates are leading the way. Parallel to the International Humanitarian City, they have set up a "Digital Response Platform": This platform brings together machine learning, artificial intelligence and geospatial technologies to facilitate information sharing among Humanitarian City’s partners.

The Emirates have a vivid history of a military-logistical embrace of Africa. In Yemen and Libya, the Emirates have learnt how to use militias for their agenda, and this is what they are now doing on a larger scale in Darfur. Following an economy of displacement, they want to drive the population into refugee camps and erect a regime of extraction and agro business.

It is obvious that local structures of resistance and mutual aid, like the Sudanese resistance committees and emergency response rooms do not fit into this agenda. When they took over El Fasher, they martyred a large number of members from community kitchens and volunteer initiatives, along with thousands of other victims.

Emergency Response Rooms as the Backbone of Relief Efforts

As state structures, in respect of supply with food, health and education are absent the Resistance Committees (RCs) and Emergency Response Rooms (EERs) have filled that void since the beginning of that war. As The New Humaitarian (TNH) wrote a few months ago,

The backbone of relief efforts has been youth-driven and neighbourhood-based mutual aid groups known as emergency response rooms – which were set up at the outset of the war – as well as other local community initiatives. With support from local and diaspora networks, as well as international donors, community responders have reached millions – running soup kitchens, supporting clinics, keeping infrastructure going, and launching education and women’s initiatives.

Mutual aid is central to many crises, but the scale and impact of local efforts in Sudan has been profound, and volunteers say their solidarity-based model offers a blueprint for both a new kind of politics and a radically different humanitarian response.

TNH has published a series of articles on mutual aid and the ERRs since June 2023, up to the article on the community kitchen in the Tawila Camp, near El Fasher, in July 2025. Meanwhile, this camp is host for many refugees fleeing from El Fasher.

The ERRs are of revolutionary origin. They were organised by Resistance Committees (RCs), which emerged as key players in the struggle against the previous Islamist regime. Many political actors were counting on the RCs to play a central role in the country's democratic transition process. Thanks to their experience with self-government and their local presence, they offered real prospects for direct grassroots democracy.

A year ago, we had a conversation with Osman Abdallah, a former activist in Omdurman. He told us that working in the RCs

was political from the beginning, but the political themes of the committees were starting from the needs of the neighbourhoods. And this is a point of strength. It wasn't a weakness like non-political. Working on the gas, the food, the transportation and so forth. They were not just working on servicing those things. [...] So it was political from the beginning, but they always say that when there is a crisis, humanitarian work is the work to access the community. But it is for a political cause.

In April this year, after two years of war, Quantara called the ERRs “A revolutionary aid network”, and in August, there was a great article on Women’s ERRs in African Arguments, by Hana Jafar, in which she also insisted on the connection between the RCs and the ERRs:

Since the early days of the mid-April 2023 war, Emergency Response Rooms (ERRs) have emerged as a practical extension of the Resistance Committees. The latter were grassroots political groups formed during the December 2018 revolution tasked with shaping the direction of the mobilization towards change. The ERRs too are more than a coordinated humanitarian response, as their work and ethos build on the Committees’ original political vision: building a grassroots civic space that is people-centred with the aim of reconfiguring the uneven dynamic between society and the state.

Adapting the Resistance Committees’ revolutionary discourse to wartime realities, the rooms became a unique sociopolitical phenomenon. They preserved their participatory essence even as their role shifted from protest organizing to service delivery. Their concept of “popular sovereignty” manifested direct citizen engagement in decision-making processes through the diffusion of power across community institutions.

The future of the ERRs remains in uncertainty. The allies of SAF, like Turkey and Qatar, will favour Islamist structures, and Egypt fears the spillover of any revolutionary heritage. In the West of Sudan, the RSF is killing every obstacle in their way. And at the same time, there is internal debates about what ERRs should be like in the future. Can they stay with their concept of democracy from below, or will they be transformed in a process which we might call “NGO-ization of a Revolution”?

A Confrontation of Discourses: NGO-isation of democratic grassroots projects

With the tides of crises and changing regimes, the involvement of international aid organisations and NGOs in Sudan has alternated between emergency aid in the periphery and traditional development aid for Khartoum. In the 1980s, which were years of drought, war and starvation in the periphery, a new docile elite gathered around the NGOs in Khartum, and adopted new practices of "NGO governance", under the umbrella of what was called a civil society. Beyond poverty and hunger, there was now talk about human rights and empowerment. The Sudanese researcher Ragda Makavi has described this process impressively in an interview with MERIP.

In the 1980s, Sudan (like many states in the global South) was subject to liberalization through its encounter with international financial institutions, like the IMF, who made economic policies and loans conditional on political and economic liberalization: With IMF conditionalities came a new civil society, heavily funded by international donors. It led to a situation of more civil society, but less representation—compared to the sort of grassroots civil society, which is something that had existed throughout Sudan’s history.[...]. With liberalization, the focus shifted firmly to a western idea of a women’s empowerment agenda, which enforced the vertical elevation of women through professionalization towards upward social mobility. This resulted in a small circle of elite women. […]

By the 2000s, Liberal Peace became the dominant framework. Funding poured into projects aligned with the Women, Peace and Security agenda (as set forth by the 2000 UN security council resolution). The irony is for all the talk on women, peace and security, at the first test, which is this current war in Sudan, if you map the terrain, you find very little presence of all these institutions and processes that were invested in for decades. Ultimately these systems isolated the general public from their own control over whatever peace is and civil society’s interventions in it. Worse still they created parallel and siloed political tracks for groups depending on their geographical and ethnic background. Peace in Darfur, as it was in South Sudan, assumes an approach and process as well as tools and a language that is separate from mainstream politics. Peace fragmented the Sudanese polity at the level of regions and communities, weakening the national sense of identity.

© Care Org

Since the beginning of the war NGO activities inside Sudan largely ceased. The offices in Khartoum were closed, the expats went home, and the Sudanese personal scattered. A report by CCU-Sudan gave an impression of the variety of groups and networks of mutual help, and especially the ERRs. Their coordination was weak and their main sources were from local contributions. So CCU-Sudan tried to connect these local actors with diaspora organizations, as well as bigger donors, with respect to their locality and self-determination. As they argued,

ERRs are best thought of not as institutions in the traditional sense but as networking hubs built around mobilising local resources using local capacities.

Since recently, the need for a different humanitarian response has been a topic of many press releases. This is the story behind it: In February 2024, three ERR organizers visited UN Headquarters and called on the international community to recognize ERRs as an actor in the humanitarian field and provide support to them. In the same year, they went online as an NGO with filmmaker Hajooj Kuka, as an “External Communications Officer”. They founded the Localisation Coordination Council (LCC), and in the USA were able to connect with the Unitarian Church as well as with the North Carolina group Proximity2Humanity. It was a great achievement that the ERRs were given the Rafto Prize 2025, and the Alternative Nobel Prize 2025. But it is worth keeping in mind the words by Jérome Tubiana:

Western policymakers now think Sudan’s woes can be cured by its ‘civilians’ and ‘civil society’ (ill-defined categories, given their fragmentation and helplessness), especially the ERRs. This is a sign that they have abdicated all responsibility for providing aid and ending the violence. The ERRs were nominated last year and this year for the Nobel Peace Prize. Never mind the Nobel, one of the founders of the ERR in Zamzam told me, the priority is to stop the war. He is now in a refugee camp in Chad, dependent on unreliable aid supplies from the West.

After the fall of El Fasher, we talked to a member of ERR Tawila. Together with MSF, they are taking responsibility for more then half a million refugees, with thousands of new arrivals from Al Fasher. They are building up a second camp, and have asked LCC for support, to no avail. They are getting some aid from WFP, NRC, and other donors. And they hope that the fragile protection by SLA will hold.

© 2025 Mohamed Abdulmajid/CARE Sudan

With this paper, we are definitely not opposing direct support to the ERRs. What we want to address here is the re-branding of the ERRs, which originate from the revolutionary RCs and traditions of mutuality, into western-style NGOs, transforming them from democratic grassroots projects into civil society projects. The before-mentioned Hajooj Kuka, for example, has re-framed Khartoum’s ERRs as "civil society projects”. As he said, “We organize with markets, traders, individuals”. Similarly, UUSC is calling for support of the Sudanese “pop-up facilities”, with they claim were founded during the COVID-19 pandemic. (Some of them were, but this is not to the point.) Similarly, in Germany, Gerrit Kurtz and Andrea Böhm recommend giving greater consideration to the ERRs. They also just skip the revolutionary origin of the ERRs. LCC may thus find more donors, but this comes with a price.

The transition from revolutionary committees to NGOs is not just about wording and branding, but a fundamental confrontation of discourses. It is about grassroots democracy versus hierarchies, collective responsibility versus career, and about the power to command voluntary work and dispose of donations. Anyone who gets involved with the big NGOs has no choice but to accept their rules. At the beginning, you are a supplicant, but access to power and money is addictive. Later, you become a supervisor and controller.

“RC was the backbone of the resistance. With the ERRs, we are doing what we couldn’t do with the RCs because ERRs are not political,” said Yan Elobaid, Fundraising Officer at LCC, when they were nominated the Livelyhood Award. And Hajooj Kula added, that they were bringing a new democracy to Sudan. We will see in a minute what sort of democracy this is about.

If you compare the Revolutionary Charter January 2023, which was produced in numerous discussions by the delegates of the committees, with the ready-made Charter of the LCC, you will see the difference of the concepts of “democracy” at the first glance. The Revolutionary Charter speaks of people's power; the LCC Charter speaks of the principles of good governance. It is made to address international donors. It talks about decolonised aid, but the main exponents, like the Fundraising Officer and two External Communication Officers, are the bearers of knowledge about Western NGO governance of the McKinsey sort. They come with their whiteboards and moderation kits, and they know before what the outcome has to be like. They feel at home in the world of paperwork, project applications and invoices. Compare this to the RC activists, who, with their spirit and with facebook, tried to get a revolutionary process going. It is a fundamentally different mentality working on both sides.

In his blog post on The Battle of Charters, Taharqa Elnour has characterised the shift of political attitudes during the Transitional Government in Sudan (mid 2019 until October 2021), and the fragmentation between the RCs, torn between calls for a “soft landing”, and demands for “radical change.”

At the center of this shift was a familiar logic: Stability first. Pushed by international donors, development agencies, and multilateral institutions, the idea was seductive—end the unrest, secure investments, and build institutions. But beneath it lay an implicit trade-off: Sacrifice justice for order, transformation for reform, and people’s demands for donor priorities.

As Elnour writes, the liberal peace model—emphasising market liberalisation, elite pacts, and technocratic governance—quickly became the dominant framework of that short intermezzo, before the military coup of 2021:

Funding streams dictated agendas, and grassroots movements were fragmented into professionalized silos competing for legitimacy through donor frameworks rather than through the street. NGOs, once seen as allies of transformation, became intermediaries in a depoliticized game. With international funding came conditionality—not overt, but structural. Local civil society organizations adapted, not by deepening their political roots, but by aligning with donor checklists. As a result, the revolutionary space became diluted—its unity fractured by the scramble for visibility, access, and survival.

One of the striking examples of these NGOs, mentioned by Elnour, is Hajooj Kuks’s NGO Sudan Civic Lab, founded in 2021, tapping into widespread youth disillusionment with traditional parties—drawing in unaffiliated activists and channeling their energy from the streets into donor-funded programs that ultimately softened revolutionary demands.

At the beginning of the war, in April 2023, there was much discussion inside and between the ERRs, whether to register with the government’s Humanitarian Affairs Commission (HAC) to obtain a legal permit to carry out their activities. As the report by CCU-Sudan points out, opinions were mixed, and conditions in different parts of the country and within the ERRs led to the adoption of different strategies. Today it is similar, as some ERRs join the LCC initiative, hoping to get some funding, while others resist strongly. They know that this initative was launched and funded by the International Republican Institute. In this context, we quote from a statement by the Khartoum State Coordination Committee of Resistance Committees, dated October 21, 2024:

We reject the so-called Resistance Committees Conference scheduled to be held in Entebbe, Uganda. […] This is a blatant attempt to circumvent and deceive in order to fulfill financial obligations agreed upon with donors in exchange for the political agenda they are trying to advance. Therefore, it is imperative for us to reveal who coordinated this event: Musab al-Mahjoub, a member of the Humanitarian Action Committee of the "Progress" Coordination Committee; Ibrahim al-Hajj, a coordinator of the American "International Republican Institute" (IRI); and Hajouj Kuka, a representative of the "Qissat" organization. These aforementioned figures have long worked as brokers to attract resistance committees to the workshops of organizations planned by international intelligence and to invest in projects with intelligence agendas targeting the resistance committees. […]

We will not tolerate this deliberate sabotage, no matter the cost. The actions of IRI coordinators, its donors, and the individuals coordinating this conference, with all its forms of undermining the independence of popular organizations and civil society groups in Sudan, hijacking their voices, and employing nearly $400,000 to influence their political positions and organizational structures, in collusion with some Sudanese political forces, are shameful. This act amounts to a full-fledged crime of political corruption, ignoring the most basic principles and values of research centers and civil society organizations, which should strive to ensure the independence of all components of the civil society space, not to polarize or co-opt them.

As can be seen from this statement, the differences are profound, and LCC is playing rough to achive their goals. We are not blaming any ERRs which are in urgent need of donations, but the problems of obedience to the donors are more valid a topic than ever. There must be other ways to directly support the ERRs. In the words by Taharqa Elnoun,

Today, that vision [of the RCs] is under siege—from bombs and bullets, but also from boardrooms and bargaining tables and regional and international “peace initiatives”. Yet the revolution endures—not only in memory, but in the quiet infrastructures of mutual aid, the networks of trust, the enduring clarity of those early vows: No Negotiation. No Legitimacy. No Compromise.

Sudanese Arguments

The analysis and experiences from within Sudan's grassroots movements offer a powerful critique of the conventional humanitarian system and present a clear, alternative path forward.

The central critique, echoed by researchers like Ragda Makavi, is that the international donor model of "civil society," established since the 1980s, has often created a professionalized elite disconnected from grassroots realities. This system prioritizes a "sanitized" language of human rights and empowerment over the messy, political work of addressing everyday socioeconomic needs. The result is "more civil society, but less representation," undermining historic, self-reliant community models.

We have asked Sudanese friends for a comment on the actual needs of aid delivery in Sudan. Their arguments are not merely theoretical but are born from the practical struggle for survival and sovereignty.

As our friend H. explained,

There are many big problems, regarding humanitarian aid. First is the small amount of aid that is dedicated to Sudan. The other which contributed greatly to the Sudan situation is the bureaucracy of the de facto government. And the difficulties of reaching out to the people with humanitarian aid, especially areas under RSF control, also getting permission from the government to deliver aid takes a long time, both HAC (Humanitarian Aid Commission, where the ERRs have to register) and SAK (where relief supplies are approved) are managed by the security bodies. So they are dealing with humanitarian aid from a security perspective which makes the aiding people of a higher cost in addition to the already destroyed infrastructure. In general the management of the aid is almost 40% of its value and sometimes more than that!!

Despite that the Sudanese people have great experience in humanitarian aid from below with the local initiatives e.g., ERRs, in buying stuff from the local market, the international NGOs do not flow with that. Of course this has something to do with the bureaucracy but also it's deeply connected to the interests of transportation companies and other capitalist factors involved in the process. There's another political dimension that lies deep in the desire of keeping the needy communities dependent on aid.

The idea of LCC was meant to coordinate between the emergency rooms and sharing knowledge and experiences but with the days transformed into a body that confiscated the decision of the local/below emergency rooms, this is a trial to transform these emergency rooms from being grassroots with their own decisions and vision into mere mechanisms for implementing the vision of the LCC. There's another problem, that LCC members are not elected or even nominated by the emergency rooms, which creates a fundamental problem: the lack of accountability, which makes their loyalty to donors greater than their loyalty to humanitarian needs and strips the spirit out of grassroots works. This is something that is intended in itself, to narrow the circle of decision and centralize it. There are efforts to bring LCC to the starting point, which should be a space for learning from each other and coordination rather than being solo in taking decisions.

The experiences shared by Razaz H. Basheir and her colleagues

with the ISTanD research center we provide a concrete contemporary example of this clash and a potential way out. Their work with Agriculture ERRs in Darfur highlights the fundamental "funding question" as a bottleneck. From the outset, these ERRs expressed a desire to move beyond mere service provision to establishing productive activities that could ensure long-term self-sufficiency.

This vision stands in direct opposition to a system of perpetual dependency. As Basheir explains, the "obvious answer" is the transformation from being fund-dependent to self-sustaining. This is not a distant ideal but a practical goal. In rain-fed agriculture, for instance, modest initial investment can allow farmers to achieve self-sufficiency within two to three seasons. The logical next step, which Basheir identifies as "the clearest path," is adding value to agricultural products through local manufacturing, thereby expanding the beneficiary base and building resilient local economies.

Beyond critique, Sudanese civil society is actively prototyping alternative funding models that align with their revolutionary principles of solidarity and self-reliance:

- The Diaspora Subscription Model: Initiatives like the Sudan Solidarity Collective in Canada demonstrate a community-driven approach where the diaspora provides direct, collective funding to specific projects, bypassing large bureaucratic intermediaries.

- The Social Assets Model: This is a radical re-imagining of resources, moving beyond monetary transactions. It involves mobilizing local, non-financial assets—a truck, a skill, a piece of land, or labour—where the return is based on sharing and collective benefit, not monetary profit. This model leverages existing community strength and distributes resources justly. This participatory model is a guarantee against hegemony and co-option. It ensures that the process remains in the hands of the people, allowing them to develop their skills and engagement. As Bashir concludes, this is, "in absolute terms... a political action." It is a direct effort to build a civic space where popular sovereignty is practiced daily, ensuring that the emergent bodies born from revolution can survive and define their own future, independent of external agendas.

Underpinning these practical efforts is a profound political imperative. The main discussion, as Bashir reveals, is about preventing the hijacking of these grassroots groups. The ERRs and Resistance Committees (RCs) are popular, revolutionary structures. The key to protecting them and preserving the "revolutionary seeds within them" is widening popular participation.

Summary and Demands

- A Rejection of Dependency:

The current international aid system often creates a professionalized class and fosters long-term dependency, eroding local autonomy and accountability.

- A Demand for Sovereignty:

Support must be channeled in ways that reinforce, rather than undermine, the revolutionary principles of self-reliance, direct democracy, and popular sovereignty embodied by the ERRs and RCs.

- An Investment in Production, Not Just Consumption:

The priority for local groups is to establish productive, sustainable economies—from agriculture to value-added manufacturing—that break the cycle of emergency aid.

- Innovation in Resource Mobilization:

Grassroots groups are pioneering non-extractive funding models based on diaspora solidarity and the mobilization of social assets, which are more aligned with their communal values.

- Participation as Protection:

Broad-based community participation is seen as the primary defense against the hijacking of these movements by armed factions, political elites, or NGOs. Solidarity must therefore aim to widen, not narrow, this participatory base.