From the Horn of Africa to the Mediterranean

February 21st, 2023 - written by: Marwan Osman and Ibrahim Al Jirefawi

This article is part of a series of articles on migration movements into, in, and out of Sudan. The compilation is dedicated to the 4th anniversary of the Sudanese Revolution. It is a collaborative effort by SudanUprising Germany and the Migration-Control.Info-project.

With this publication we want to contribute to knowledge about the situation of the precarious populations in Sudan – refugees, displaced people, and marginalized populations in the big cities as well as in “the periphery”- the areas outside the centre of the country and its main towns. We accompany people on the move and shed a light on their experiences and the injustices they face, which are so severely increased by EU migration politics. Most certainly, the mass murdering militias of the Janjaweed would not have grown as they did without European tolerance and support, parallel to the support for the Libyan militias which pretend to be a coast guard.

We will publish the articles in 3 languages at the same time: AR, EN and DE. The next articles to follow, on a weekly basis, are on

- The experiences of women refugees in Sudan,

- Ethiopian Refugees in the Triangle City,

- the experience of Sudanese Immigrants in Libya,

- an overview of migration movements, state politics, and displacement,

- the European support to the Janjaweed,

- two articles on refugee camps,

- refugee resistance in North Africa,

- the situation of Sudanese refugees in Europe.

From the Horn of Africa to the Mediterranean

By Marwan Osman and Ibrahim Al Jirefawi

Abdou Karim's Long Journey

We met one evening in late July 2022 in the courtyard of the first reception center in the city of Eisenhüttenstadt. He was in his late thirties, perhaps approaching his forties. He spoke Arabic in a pleasant way, mixing standard Arabic with its Sudanese, Chadian and Libyan dialects, as part, perhaps, of what linguists refer to as “building and rebuilding identity among immigrants” (Al Khair 2021). He initiated speaking with me by saying: “Are you new here?”. I replied, “yes, I only arrived today”. We were then swept up in a flood of questions to get to know one another.[1]

Did you reach Europe through Egypt or Libya?.

He replied: “Through Libya, of course!”

And why of course?

„Because most of those wishing to cross the Mediterranean to European lands depart from the Libyan coast, due to the short distance between the two coasts.“

Then you must have crossed Sudan?

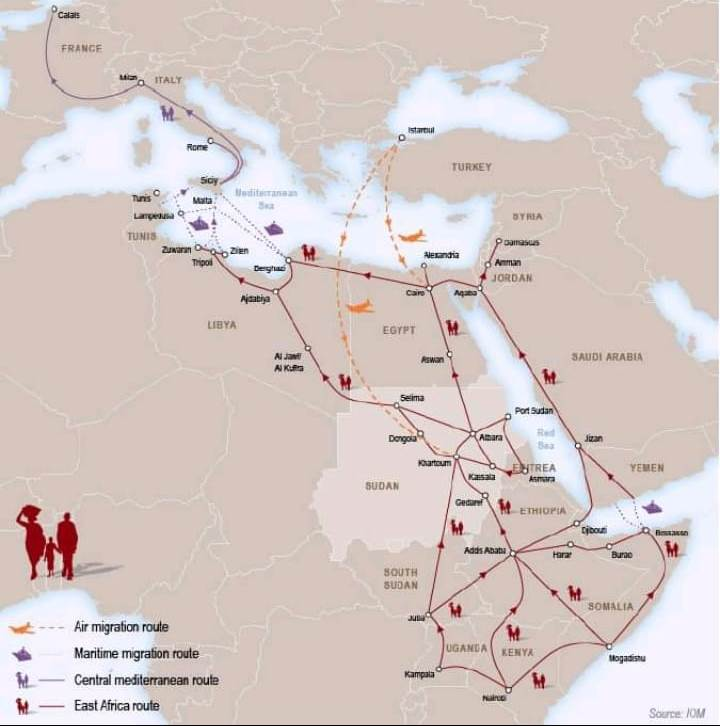

„Yes, I left Somalia to Ethiopia, then to Sudan, Chad, and finally Libya.“

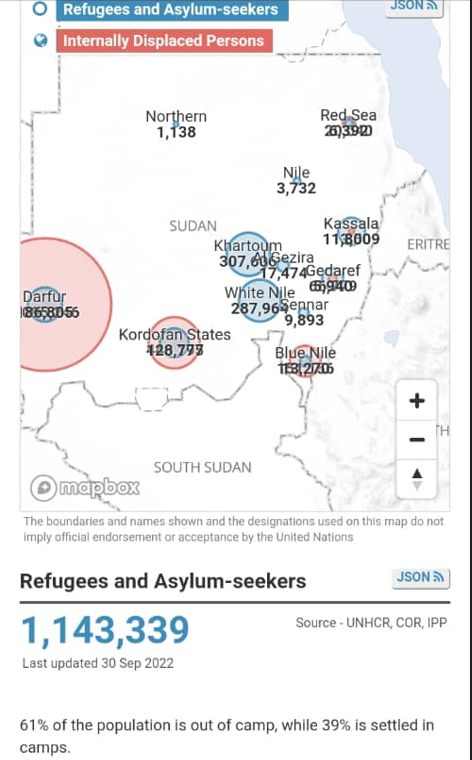

What a long journey people make to escape the hell of wars, famine, and disasters, and in pursuit of their dreams of safety, freedom and a comfortable life! The Horn of Africa has witnessed successive decades of turmoil and instability. Somalia is living a civil war that is now entering its fourth decade, while Ethiopia has been cursed by one of the longest wars in the history of the continent, which resulted in the independence of Eritrea in 1991. Eastern Ethiopia suffered from successive droughts that have threatened the lives of more than 10 million people, and according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the Horn of Africa region is now witnessing the worst drought in forty years, extending from Eritrea in the north, through Ethiopia and Djibouti, and to the southern outskirts of Kenya and Somalia (Press release, June 2022). Flooding, another natural phenomenon, also caused the loss of crops in central and southern Ethiopia, to add to the civil war that broke out in the regions of Tigray, Oromo, and Benishangul-Gumuz. As for Sudan, which coincidentally has a geographical location linking the east of the continent to its west, north, and south, the country has continued to suffer from civil war since the eve of independence in 1955.

Was it difficult for you to enter Sudan?

„No, it wasn't difficult.“

How long were you in the refugee camp?

„I didn’t stay in the refugee camp because I didn’t enter through the official crossings between Sudan and Ethiopia. Rather, I was smuggled across the border, and I arrived in Khartoum in just a day.“

Abdou Karim is right: the Sudanese-Ethiopian border, which is about 1,600 km long, is considered one of the most complex areas in terms of its mountainous geography, a geography that has resisted state control and the rise of elites for centuries (Gonzalez 2012: 67). Its inhabitants have resisted all kinds of state injustice and political inequality, since it acted as a haven for those who opposed the state or were fleeing its oppression, such as cultural minorities, warlords, or rebels and bandits (Triulzi 1981). In general, the (Sudanese / Ethiopian) borders, with their low population density, are seen as a receiving land for human migrations, whether permanent or temporary seasonal ones. Most of the current population arrived in the region in the past seventy years. In addition to the temporary expansion of the state (Ethiopia or Sudan) or migrations that reach the region, the border area is also associated with three important phenomena. The first is the conflict between the state and non-state societies, and tribal conflicts. The second is that it also acts as a space for middle-ground cultural encounters between the state and its subsidiaries on the one hand, and horizontally organized societies on the other. As for the third phenomenon that is associated with these borders, it is the emergence of new cultures, (ethnogenesis) and its opposite—human extermination or ethnocide (Hall 2000: 241).

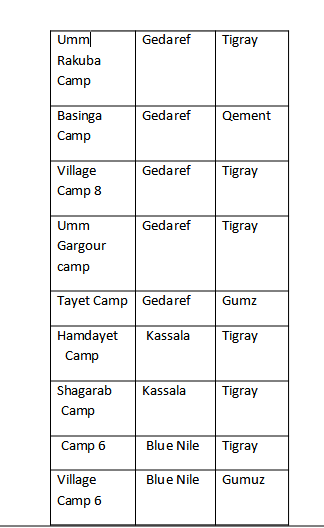

This introduction to the Sudanese-Ethiopian border is necessary to understand the reality of human flows across it. It should be noted that those arriving through the official crossings are crowded into six camps:

(Sources: COR registration database)

These camps lack the most basic of life’s necessities, and are more like prisons, where residents are neither allowed to leave, nor are they granted a permit to work or receive any kind of financial assistance.

I asked Abdo Karim: how did you find life in Khartoum?

”Regardless of the economic suffering, the refugees are harassed by the Sudanese authorities and blackmailed by the Sudanese police.”

Karim is right again, as, since 2016, the Sudanese authorities have withdrawn refugee cards from many, allowing police forces to arrest them on the pretext that they do not have refugee cards or a work permit. As such, one is forced to empty everything in one’s pocket as a bribe, and the situation may happen to a person more than once.

The Hellish Road to Libya

After the fall of Al-Bashir in 2019 and the advent of the transitional government, there has been no change in the conditions of the refugees. In November 2020, in protest against these conditions and to demand their rights, a group of Ethiopian and Eritrean refugees staged a sit-in in front of the UNHCR building. The response of the transitional government was to repress them, arrest a large group of them, and transfer the others to the south of Khartoum. After the transitional government adopted policies to withdraw subsidies and liberalize prices, the economic crisis deepened and the conditions of the Sudanese in general and of the refugees in particular, worsened, prompting many of them to take the desert migration route towards Libya.

I said to Abdo Karim: Tell me about the road to Libya.

“After we paid one of the smugglers, he asked us to pay the value of food and drink, after which they took us in a car from West Omdurman towards the desert. It took four days until we reached a military group near the border. We thought it was the Libyan border, that is until another group came with open and armed Land Cruisers. He asked us to go up in the vehicles after a walk that lasted for several hours. We were taken aback that we were in Chad, discovering also that we had been sold to a Chadian militia operating on the border between Chad and Libya (Karim could not precisely name this militia). This group asked us to pay again in order to take us to Qatroun in Libya. They provided us with a bank account number to deposit the money and also asked us to contact those who could pay for us. We stayed under a tree for about ten days, waiting for transfers. In the end, they took those of us who were able to pay to Al-Qatroun, and I was among the lucky ones, since my uncle, who lives in Sweden, paid the money.”

Karim’s story coincides in some parts with the two stories of M.M, 16 years old, and A.A., 18 years old, whom the Safe Road Initiative met in January 2021 in Al-Daim neighborhood of Khartoum.[2] The two were transported from Libya Market, west of Omdurman, in an open SUV belonging to the Rapid Support Forces. When they reached Maliha, they were transferred to another car, while yet another car with an armed crew followed them – they were told that it was a car for protection. These two people were not as lucky as Karim, as they did not see Libya at all, but were detained by the Rapid Support Forces militia for more than six months, during which time they were forced to work for the militia – cooking, cleaning the camp, washing clothes, and carrying boxes of ammunition. After the condition of M.M.'s hand—which was broken by a militia member who beat him with a stick— worsened, M.M. became unable to work, so his mother was contacted, and a ransom was demanded from her. His mother was forced to seek help from a large number of people, until she was able to collect the required amount and hand it over to one of the militia members in the Libya market area. The family was warned not to talk about the matter, otherwise, they were told, they would not see their son again. He would be gotten rid of, even post-return, if the matter became public.

According to an expert familiar with the desert trails, migrants set out through one of the following points: El Fasher, An Nahud, Mellit, Umm Kadada, Umm Ujaija, Um Badir, Jabal Maydoub and Al Mashroo’ — these are the roads on which there are water wells. Most of the covert border crossings into Libya are carried out by camels to avoid facing the problematic issue of fuel scarcity. This process begins after preparing food supplies, which usually consist of dry bread or Kisra [fermented flatbread], flour, onions, sugar and tea, in addition to large amounts of water carried in goat-skin canisters. One camel carries six canisters.

The caravan usually consists of ten to fourteen camels, and human smugglers often choose to move at night through Wadi Howar, North Kordofan, because it contains water wells; it is a harsh, barren desert with no life. After Wadi Howar there are no sources of water except in the Uwainat Triangle area on the Sudanese-Libyan border, from which the clandestine migrants depart to Kufra (about seven days by camel and twenty-four hours by car). As for the journey from El Fasher to Benghazi, it takes thirty-seven days by camel and five days by car in the absence of breakdowns or any other emergency.

Travelers get lost in the desert and die of thirst because they always choose the remote desert paths, away from the eyes of the Sudanese militia forces and the Libyan border guards. The distance and the high temperatures force them to consume the full amount of water in their possession within a few days. A survivor who had been traveling by camel back said that the forty-one travelers (of whom he was one) had consumed all the water in their possession when another convoy found them in the Jubail Al-Deira area. Only two were still alive, while the rest had died, their bodies found stiff, their skin peeled from the heat. One of the survivors said that they had set off from Wad Banda in North Kordofan and continued to travel in the desert for twenty-eight days, avoiding militia positions, until the camels became exhausted and refrained from walking. The travelers ran out of water, so they slaughtered the camels and drank their blood. He believes that this might be what saved his life, since the others refused to drink the camels’ blood. The eyewitness says that they also found sixteen human skeletons in the Shajar Bidi area, about 150 km north of Wadi Howar. Near one of them was a passport and an identity card in the name of Abdullah Ahmed Jidu. In addition, they found a list of the dead near the body of the guide.[3]

The Rapid Support Forces

Travelers die during their attempts to avoid the Rapid Support Forces and the Libyan Border Guard, which are supported by the European Union.

The name Rapid Support was officially adopted to describe the Janjaweed militia and legalize it as a force affiliated with the National Intelligence and Security Service in 2013. Muhammad Hamdan Dagalo was appointed as leader and granted the rank of brigadier general, with the main tasks assigned to these forces limited to combating rebellion in Darfur, South Kordofan and Blue Nile. Many crimes committed by the Rapid Support Forces in those areas have been documented, in addition to their role as border guards deployed in the border triangle between Libya and Sudan (Jebel Al- Uwainat) to combat migration.

After the famous protests in September 2013 in Khartoum, Wad Medani, and other Sudanese cities, the security apparatus announced the introduction of a Rapid Support Force in Khartoum, which is the force that is primarily accused of killing more than 200 demonstrators. In the period 2014 to 2018, developments took place that made the Rapid Support Forces a major power and parallel force to the army. It was directly attached to the Presidency of the Republic in June of 2016, and infantrymen and fighters from the Rapid Support Forces were sent to the war in Yemen and to protect the Saudi borders, with an estimated number of more than 5,000 mercenary soldiers deployed.

As a result of the movement stemming from the December 2018 revolution, on April 11, 2019, the Rapid Support Forces, along with some leaders of the Sudanese Armed Forces, removed President Al-Bashir and arrested him. They formed a military council with General Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan at its head and Mohamed Hamdan Daglo as his deputy, then asked the protest leaders to negotiate a new constitutional arrangement to manage the transitional period. The negotiations lasted for two months, during which time the protesters occupying the area in front of the General Command refused to accept the military’s conditions. The military dispersed the sit-in on the morning of June 3rd, 2019 in a bloody manner, in what became known as the Khartoum Massacre. The Rapid Support Forces are considered the main military force that committed the crime of dispersing the sit-in.

Internet service was cut off in Sudan for more than a month, and the Rapid Support Forces deployed heavily in the main cities to suppress protests, until the masses came out on June 30th with “millionyat” (protests of millions) in all cities of Sudan. After that, negotiations resumed between the military and Forces for Freedom and Change (the political body that represented the demonstrators at the time). These negotiations produced a constitutional document for the transitional period, which resulted in a government of partnership between civilians and the military. In this government Muhammad Hamdan Dagalo assumed the position of deputy head of the Sovereignty Council.

It is worth noting that the constitutional document for the transitional period 2019 Amendment 2020 legitimized the Rapid Support Forces and referred to them as a force parallel to the Sudanese Armed Forces and subordinate to the Commander-in-Chief and the sovereign authority, while simultaneously preserving its independence.[4]

On October 25th, 2021, the army commander, General Al-Burhan, with the assistance of the Rapid Support Forces, carried out a coup d’état against the government of the transitional period and disrupted the implementation of the articles of the constitutional document. Despite the fierce popular resistance of the military coup, which has continued now for over a year, the coup-makers still control state institutions, with the Rapid Support Forces playing an effective role in protecting the coup.

After the military coup, Muhammad Hamdan Dagalo hastened to issue warnings to his European allies that his country might be a source of refugee flows to Europe in the event of non-cooperation with his new military government. He further said in an interview with Politico that the government will work to stabilize the situation of refugees in that moment, and requested cooperation and recognition of the new government. He added, speaking via video call from Khartoum: “Because of our commitment to the international community and the law, we are keeping these people with us.” “If Sudan opens the borders”, he added, “there will be a big problem around the world.”

Following that, the Rapid Support Forces inaugurated the Desert Shield Forces and deployed them in the border area of the Triangle. Desert Shield are forces with military equipment and training in the field of immigration control and border-guarding. They were sent off in official ceremonies and celebrations that were broadcast on national television and media platforms affiliated with the Rapid Support.

Photo credit Maimoon Yusuf

The Rapid Support Forces has dedicated platforms, websites, and pages on social media to promote its forces and to improve their image, presenting them as carrying out major humanitarian work in combating human trafficking, rescuing migrants in the desert, providing psychological support, and helping migrants return to their homelands. The Beam Reports observatory, which specializes in exposing fake content on social media, revealed that the Rapid Support Forces are making strenuous efforts to improve their image through foreign media interfaces that they use to spread misleading information. The report revealed the militia’s cooperation with European agencies and centers in France working to improve its image, specifically as pertaining to the immigration issue.

Muhammad Hamdan Daglo stated in a television interview with BBC in August 2022 that there is no cooperation between his forces and the European Union at present, except for with Italy, which he thanked for its cooperation and the continuous support it has provided, for two years, to his forces. Also, since last October, the Rapid support Forces’ electronic media, through its official platforms, has been broadcasting documentary film material in different European languages about the role of the militia in combating illegal immigration.

It is clear that this content was produced at huge cost, working with bodies specialized in public relations and speaking to the European allies. All the above explains strategic position of the Rapid Support Forces regarding its relationship with the European Union, and that these forces will not give up their role as guarding Europe's borders in the desert so long as they consider it a permanent source of funding, and a card to be used for international blackmail.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it can be said that the most dangerous issue facing migrants from Sudan to Libya is not thirst and losing their way in the desert. Rather, it is the large deployment of these forces involved in human rights violations, crimes against humanity and human trafficking— with the support of the European Union. The latter is working hard to extend its borders to the African interior to combat migration, without paying consideration to the crimes of the Rapid Support militia and while providing financial and technical support to the militia, in blatant disregard to the principles of human rights and other human and moral values.

Literature

Al-Khair, Suliman (2020): Identity construction among Ethiopian Migrants in Sudan [AR]

Baldo, Suliman (2017): Border Control From Hell, How the EUs Migration Partnership Legitimizes Sudan's Militia State. Published by Enough Project.

Gonzalez-Ruibal, Alfredo (2012): Generations of Free Men: Resistance and material culture in Western Ethiopia, in: T. L. Kienlin and A. Zimmermann (eds.): Beyond Elites. Alternatives to Hierarchical Systems in Modelling Social Formations. Bonn, pp. 67-82.

Hall, Stuart(1996): Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, Routledge

Triulzi, Alessandro (1981): Salt, gold and legitimacy: prelude to the history of no-man’ s land, Belū Shangul, ii al-laggā, Ethiopia (ca.1800–1898).

Footnotes

-

Interview with Abdou Karim, July and August, 2022, Eisenhüttenstadt, Germany.

↩ -

Interview with M.M. and A.A. January 2021. Al-Daim, Khartoum. Sudan.

↩ -

Interviews conducted by Al-Taj Othman, Al-Rai Al-Aam newspaper 2021.

↩ -

Official Gazette of the Republic of Sudan Constitutional Document for the Transitional Period, Chapter Eleven - Regular Forces.

↩