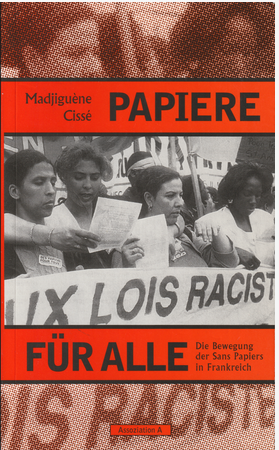

Madjiguène Cissé passed away

May 18th, 2023 - written by: migration-control.info

Madjiguène Cissé died on Monday in Dakar at the age of 72. Activists in Europe owe a lot to this courageous woman. Christian Jakob wrote an obituary in the taz. Here is the speech Madjiguène gave on the occasion of the awarding of the Carl von Ossietzky Medal on December 6, 1998.

The struggle of the Sans Papiers: A fight for human rights

On 18 March 1996, 300 West Africans (from Mali, Senegal, Guinea and Mauritania) suddenly appeared; like coming out of a tunnel, blinded by the headlights of the TV cameras, they demanded their legalisation with great matter-of-factness.

Thus began a conflict with the French state, which was to last several months.

Since ten o'clock in the morning, all of France knew that something was going on in the Saint-Ambroise church: the "illegals", "les clandestins", as we were called, didn't want to take it any more, to be constantly harassed, hounded and relegated to the back row: We were there, flesh and bones, clearly visible and determined to take our fate into our own hands.

We demanded papers for all from the very beginning in order to avoid a split, avoid divide and prevent arbitrary decisions.

We have always regarded it as our right to demand papers.

Deprived of fundamental human rights, mostly illegalised through special laws, which - especially since 1974 - have been constantly tightened up, according to the closure of the borders - we had no other choice than to put France, its institutions and its public opinion to the test.

We attacked the French laws that punish us, and thus wanted to emphasise that a society cannot exclude a part of its population in the long term without these excluded people questions the system itself.

The coup of 18 March 1996 was, it can be said, a Rebellion: against harsh living conditions like illegalisation, against the violation, the negation of our rights, against the humiliations and degrading treatments of which we were victims (facial checks, arrests, imprisonment, deportations ...).

Three things were of great importance in our eyes:

- A clear demand: papers for all!

- Our visibility, necessary to make the demand, possible only with the conquest of our autonomy

- This autonomy itself.

Even if each one of us is responsible for his or her own demand for other life circumstances, so we have together, as a group, quickly understood that our struggle meant more than the question of the papers and therefore could not limit itself only demand papers for our group.

We had to organise ourselves, that was the prerequisite of our resistance. The expansion of the movement became a necessity, I was particularly committed to this, even for the prize of some of my comrades-in-arms sometimes not understanding me.

Sans-Papiers collectives formed throughout France and coordinated, first at the regional level, then also nationwide; 8 nationalities were represented in the national coordination. Our demands were highly political. That we made us so visible - through demonstrations, rallies, discussion rounds, caravans throughout France - this certainly disturbed. Everything was done to stop this - and to prevent the generalisation of our group's demands:

Papers for all.

More often than not officials of the police prefecture of Paris recommended that we take care of our applications alone. "Why don't you take care of your own applications? Everything would be easier for you. Why demand papers for everyone?“

Once we had agreed on the objectives, we had to to link our struggle with the social movement, not to conduct it in isolation, but make it understandable as a struggle of a part of the working population. The result was a rapprochement with the trade unions. Trade unions took over sponsorships for all Sans Papiers of Saint Bernard, and the Bourse du Travail, the trade union house, still today offers to us its premises for our meetings.

Support committees have formed around around each of our own committees. But as much as we want this support, without which we would not be able to continue, we also value our own autonomy.

I was not the only immigrant in our group who had combined our struggle with the hope of making our voices heard: take the floor, challenge the representatives of the French state, make the national and international public to witness.

I myself had been familiar with social movements for a long time, I had already participated in all major initiatives and protests in Senegal, after the great riots of 1968.

The attempt to integrate our movement into that of the unemployed in the winter of 1997, all the joint meetings and all the occupations were also aimed at countering the right-wing extremists' argumentation, which were taken up by both the left and the right, that foreigners were to blame for the unemployment rate, and their expulsion would solve the problem of unemployment.

By working and fighting side by side, we wanted to draw attention to the real causes of unemployment and to social problems in general. We have explained that the real reasons for all these problems lie in the economic policy of the government, a neo-liberal austerity policy and not in the alleged "laziness" of the unemployed or in the pretended "parasitism" of the "illegals".

By coming into the light of day, we have decided not to ask for our legalisation, but rather to to fight for a change in our situation. The Pasqua Laws of 1993 were the culmination in the deprivation of our Rights. We, the victims of this xenophobic legislation, who have been pushed into a zone of no-right, we have risen up and denounced the human rights violations in France:

Right to move in, right to settle, right to work, to housing, to health and education, to education for the children, to a normal family life, because the rights of women with Children are mocked on a daily basis; right to citizenship, right to asylum ...

The exercise of these rights - some of which are enshrined in national and international declarations - is restricted by the legislation on immigration, by provisions with the sole aim to control, bully and oppress.

All is set to make clear to the foreigners living in France that they have no rights.

For those who are to be prevented from coming, the right to freedom of movement no longer exists.

For those who are to be prevented from settling, there is no longer any right at all: everything is done to make them feel rejected, that their living conditions are made unbearable.

Encroachments and arbitrary administrative practices become part of everyday life, and for particularly zealous officials, denunciation becomes a civic duty. Thus, the administration's terrorism is more and more just the first step before applying the law.

Our action - beyond the demand for papers - raises the question of freedom of movement and the question of immigration in general. It is the question of human rights and their violations which Question of the general validity, the universality of human rights.

On the threshold of the 3rd millennium, the action of the Sans Papiers in France make the major international migratory movements to be a topic. We come for the most part from countries of the so-called South, whose economies have been plundered for centuries, and which today are supported by the structural adjustment programmes of the World Bank and IMF to be paralysed. Our struggle here, in a country that has become the North, sets the question of North-South relations, of the distribution of planetary wealth, on the agenda.

What significance do human rights have for the millions of illiterate people who live in poor countries and are not able to make use of them? Do they even know about their existence?

What do human rights mean to four fifths of humanity, who are forced to live in the greatest misery, on less than a dollar a day?

What is the significance of the demand for the right to self-determination for peoples in the age of economic globalisation?

The defence of human rights should begin with defending the right to development, to the well-being of every individual. Freedom can only take its course in the struggle against misery, against the obvious global inequalities.

Our struggle is a struggle for equal opportunities and for equal rights, for a new world economic order.

If our movement was extraordinary, in terms of the determination of its actors and in their hunger for autonomy, if they bring a certain dynamism to the social movement in France - our struggle could not exist isolated, and can not exist isolated in the future.

Let's continue to build bridges to the movements of the unemployed, the homeless, the workers in France and Europe and in our countries of origin!

This is also the reason why we support the campaign "Kein Mensch is illegal", which is currently being organised in Germany. Develop and consolidate actions at the grassroots level, established on the principle of democracy - that is more than necessary, that is long overdue. As Sans Papiers, we have quickly learned that we are ourselves the first defenders of our rights. Our movement, which took place barely three months after the strike of the French workers in the Winter 1995 shows that a completely different path than that of submission and fatality is possible.

Our actions aim to make human rights a reality and, if necessary, also beyond the scope of the state legality.