Update: The Emirates and the War in Sudan

February 18th, 2025

For this blog post, we have compiled material about the War of Displacement in Sudan and the involvement of the Emirates (UAE). The Emirates are often seen as players on the sidelines, when it is not about major sporting events, airlines, conferences or tourist highlights. In fact, however, UAE is a prototype for a new model of regional imperialism: extractionism, development by displacement, and the exploitation of a low-paid labour force without democracy. The Emirs see labour as a returnable imported commodity, the state is run like a family business, and it is maintained by a small Emirati elite with servants from all over the world. Extractionism results in militia wars, displacement, and hunger crisis, especially in Sudan.

In our Dossier on Sudan, our main interest was the Sudanese Revolution, and the social basis of this revolution, namely the Resistance Committees, and the social networks of the everyday life, and also the growing strength of the women in the revolutionary process, and the overcoming of „tribal“ sentiments.

We have then analysed the War in Sudan as a destruction of that revolutionary social fabric. Now, the longer this war is going on, the more we are concerned with the UAE asserting their interests and securing their investments at all costs, against all precepts of humanity. And more and more we see that UAE is not only securing their investments, but cleansing new fields for investment, by displacing the population.

Our Core Messages

UAE is deliberately prolonging the war in Sudan, not only because it takes profits from both warring parties, but mainly because it sees displacement as an investment in the future of extractive economy, minerals and agriculture. The exports from Sudan to UAE are higher than ever, during the war.

For UAE, Humanitarian Aid is a business. Dubai is the biggest humanitarian hub of the world. They use humanitarian logistic as a door-opener for commercial logistics and investment. The Military-Humanitarian intervention is in the core of their strategy.

The Emirates have established a Regional Imperialism, using military interventions by proxy, logistics, land-grabbing and Green Colonialism as tools for regional supremacy.

The Emirs run their state like a family enterprise. They extract a workforce of 9 million mainly from Asia, and they extract minerals and food from Africa. Behind the fassade of a golden touristic destination, a strong police force, and the secretly operating State Security Apparatus crack down on any forms of self-organization and protest.

Who could stop UAE?

It is impossible to talk about the war in Sudan without shedding light on the role of the UAE. Authoritarian, aligned with the West, engaged in war against any revolutionary uprising, a paragon of global capitalism, a leader in the exploitation of uprooted labour and the valorisation of African resources, the Emirates are a major player in the background of war, displacement and genocide around the Red Sea and beyond.

What power could stop them? The Emirates have nothing to fear from the political class in the USA, nor in Europe. The special friendship with US President Trump, the hosting of US military bases, the recognition of Israel in the Abraham Accords, and the "energy partnership" with Germany - all this has been headlines in recent years. Behind these headlines, there is a silent accord, which can be traced back to the 1970s and the mechanism of "petrodollar recycling".

In the early 1970s, the situation in the Western economies was characterised by workers' struggles: wage demands and the struggles for the expansion of the welfare state caused inflation, which was exacerbated by rising energy prices. In this situation, the "Oil Crisis" of 1974 became a game changer: siphoning off mass purchasing power, and accumulation of dollar assets in the hands of OPEC. In the years that followed, economy changed from demand- to supply side, and the worker's struggles were silenced. However, the OPEC assets were re-invested in the Western economies, or used for arms purchases. This meant that the Western capitalist economies did not suffer, while the working classes did. The Eurodollar market was the starting point for a transformation from Keynesian towards Global Capitalism, which began with the rise of the financial markets and has since produced a world of weapons and digital technologies, and also a world of hunger and genocide. As it seems, the historical episode of Western democracies and Human Rights is also coming to an end.

We remember well the visit of Minister Harbeck in Saudi Arabia and the Emirates, and the performance of the Emirates on the COP 29 in Baku. Recently, the “European Council on Foreign Relations” has stressed the common interests of Emirates and EU, and has recommended to “harness die UAE’s energy ambitions in Africa”:

By cooperating with the UAE, the EU could help fast-track the implementation of green initiatives in Africa and promote pragmatic solutions for the energy transition, possibly also improving its appeal as an inclusive partner in the global south.

[Update: On April 10, 2025 The New Arab wrote:

"Today, (the European Commission) President von der Leyen held a cordial phone call with His Highness Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, President of the United Arab Emirates. During their discussion, they agreed to launch negotiations on a free trade agreement," the EU said in a statement. The talks will focus on trade in goods, services, investment and deepening cooperation in strategic sectors, including renewable energy, green hydrogen and critical raw materials, the EU said.]

What is the German government saying?

The German Foreign Office writes on their homepage:

Germany and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) maintain intensive diplomatic relations. The strategic partnership agreed in April 2004 is an expression of this. In September 2022, Federal Chancellor Scholz agreed to revitalise the Strategic Partnership during his visit to the UAE together with the President of the UAE, Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan. In 2023, the Emirates were once again Germany's most important economic partner in the region with a bilateral trade volume of over EUR 14 billion. German imports from the UAE increased by 150% in 2023, with around 1,200 German companies based in the UAE, many of which cover the entire region including (parts of) Africa and Asia. The German-Emirati Chamber of Industry and Commerce, headquartered in Dubai and with an office in Abu Dhabi, supports the trade exchange. In addition, the energy partnership between Germany and the UAE to promote cooperation in the field of renewable energies was expanded to an energy and climate partnership in November 2021.

LondonforSudan: We are calling for a global strike of the UAE. The UAE are the biggest funders of the RSF, the militia group that is currently committing war crimes, destroying and destabilising Sudan by supplying weapons, ammunition and military aid. Sudanese blood is being spilled for the UAE’s gain. Time to sanction, exclude and divest from the UAE!

The War of Displacement

Since the beginning of the war, April 15, 2023, the RSF mercenaries have more or less systematically displaced the populations from areas which they either want to sell for agroindustry or use for cattle ranches. The other warring party, the SAF, and associated militias, have committed atrocities as well, like bombardement of busy market places. Both sides have followed a strategy of starvation, by blocking deliveries of humaitarian goods. This is why 25% of the Sudanese population is at the brink of starvation. The Danish Refugee Councils spoke of “historic proportions” of a starvation crisis already last summer. Both sides are following a strategy of driving the population into refugee camps, and select them on their way, according to “tribal” criteria.

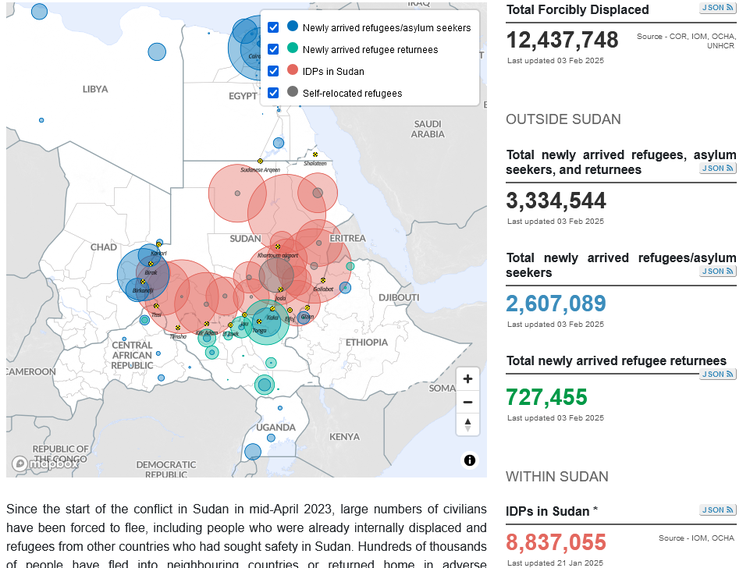

This visualisation, which is regularly updated by UNHCR, shows the situation as of February 2025: More than 12,4 Million forcibly displaced, near 9 Million displaced internally, and 3,3 Million have crossed the borders, since April 2023. Many of these people will never be able to return. Their villages have been burnt down, and their land is being sold to investors.

Numbers of people being displaced are somewhat abstract. This is why we would like to present two footages, about what displacement looks like. The first one shows a treck of Massalit refugees after the attack on Genana, by the RSF, in June 2023.

Please find footage here. In the foreground you can see boys from the Arab tribes from which the RSF also originates.

The second footage is about RSF militia driving the polulation out of Danlj, a village in Nuba mountains:

Please find footage here. Just recently, RSF has killed hundreds and driven out thousands in the White Nile state villages of al-Kadaris and al-Khelwat.

The displacement started with the Massacre of Geneina, June 06, 2023. During that Battle, up to 15 000 people were killed and 370 000 persons were displaced from that town and it’s surroundings. In October, RSF took Nyala and spread the war to Gezira, into the main irrigated agricultural area. Many thousand fled to the regional capital, Wad Madani, which was taken by RSF in December. In May 2024, during the Battle of Al Fasher, the RSF have razed settlements to the ground in an area of one and a half square kilometres within two weeks- through bombing, fire and ground troops. In June, RSF killed more than 200 persons in a massacre in a village of Gezira. Hundreds thousand fled. RSF usually spreads footages of their atrocities on their channels, thus causing fear and fostering displacement. June 2024 not only witnessed the escalation of war in Omdourman, but also in the states of Sennar and Gedaref, which are also important agricultural areas. The attack on Sennar again led to mass displacement. Sudan’s war parties systematically used starvation as a weapon. At the same time, floods displaced more people, but also paused the war. In October 2024, The RSF’s use of terror tactics in Gezira State resembles the tactics they previously have used in Darfur. At the same time, RSF burned 17 villages in Dar Zaghawa of North Darfur State, according to satellite imagery.

During the last weeks, RSF is withdrawing from the Khartoum and Omdurman area, and concentrating it’s forces in Darfur. More attacks on El Fasher are looming, which is the capital of North Dafur state. There is high risk of the next action of genocide, completing what has begun in the Darfur War of 2003.

Also, if RSF can take El Fasher, this will lead to the next separation of Sudan (after the secession of South Sudan, in 2011). The Emirates will appreciate this. They do not care about states, but they care about assets and Real Estate. What Trump is planning for Gaza, the Emirates have been doing for years. For the development of Real Estate, population is just an obstacle.

More Info:

18.11.23 MC Info: I Was a Witness to Your Death, Oh Geneina: The city of El Geneina did not die due to the forced displacement that occurred on June 14, 2023, but it died gradually due to the repetition of painful incidents that burdened the life

19.01.24 VoA: UN Report Says Ethnic Violence Kills Up to 15,000 in 1 Sudan City: Between 10,000 and 15,000 people were killed in one city in Sudan's West Darfur region last year in ethnic violence by the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and allied Arab militia, according to a United Nations report seen by Reuters on Friday.

26.06.24 Guardian: Sudan’s warring factions using starvation as weapon, experts say: “Both the SAF [Sudanese armed forces] and the RSF are using food as a weapon and starving civilians,” the experts said. “The extent of hunger and displacement we see in Sudan today is unprecedented and never witnessed before.” Neither the military nor the RSF returned phone calls seeking comment.

14.10.24 MC.Info: Ignoring the root causes of the disaster: the EU and Sudan: Ten million displaced people, two million who have fled to neighbouring countries – but the EU's chief concern relates to the 8,000 Sudanese who have made it into the EU “illegally,” most of them on the deadly route across the Mediterranean. The document refers to “resilience.” It is “European” resilience, not that of the people fleeing. In the interplay between coastguards and militias, the EU’s asylum system and Frontex, what is meant by resilience other than “keep them out”?

14.11.24 AJE: Visualising the war in Sudan: Conflict, control and displacement: The world’s worst internal displacement crisis, with at least 14 million people uprooted from their homes, is in Sudan.

03.02.25 AJE: As Sudan’s RSF surrounds Darfur’s el-Fasher, ethnic killings feared: Sudan’s army could lose the last major city it controls in the western region of Darfur within days to the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), according to analysts, local monitors and RSF sources.

Observers fear this could lead to crimes against humanity by the RSF and a humanitarian catastrophe in el-Fasher, the capital of North Darfur state.

18.02.25 Guardian: Sudan paramilitary group kills more than 200 people in three-day attack, activists say: The attack on the White Nile state villages of al-Kadaris and al-Khelwat, 100km (60 miles) south of the capital, sent thousands fleeing, witnesses said. A spokesperson for the UN secretary general, António Guterres, said the world body had received “horrifying reports that dozens of women were raped and hundreds of families were forced to flee”.

Emergency Lawyers said that for three days RSF fighters had subjected unarmed civilians to “executions, kidnappings, forced disappearances and looting”.

The UAE – RSF Connection

The Profits of War

The main reason for UAE to support the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) against the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), the national army, is that this war serves the UAE’s interests in defending their enormous investments in Sudan. Any successful democratic or revolutionary experiment in their sphere of influence is perceived as a threat, justifying extreme measures, even if it means destroying a country harbouring such sentiments.

„The war that the RSF is waging, with the support of the UAE and others, is not a conventional war, but rather a war to dismantle the Sudanese state and subjugate the Sudanese people“. Mahjoub, Husam (2024)

However, this does not mean to say that SAF is a democratic institution! The main thing for the Emirates is to prolong his war, because they are profiteers of the war: they extract more gold than ever, and they prepare more investments by displacement of the rebellious population. In fact, without the direct and all-around support of the Emirates,, the RSF would not have been able to wage this long and relentless war.

.

But why is RSF the prime partner for the Emirates?

- MBZ and Hemedti are Business men, they follow the same relentless commercial logic.

- RSF have proofed their loyality to UAE. After the genocide in Darfur, 2003, the then Janjaweed established strong commercial ties to UAE, and have since then delivered gold and cattle from Darfur. Also, they manned the Security to guard the UAE`s enterprises in Sudan, and sent militiamen (and children) to Yemen in 2015. All RSF business, finance, logistics and PR operations are carried out from the UAE.

- On the other side, the SAF comprises Islamic factions and militias which UAE does not like. They hate Islamism, although they hate democracy from Below ecen more than this. They like strongmen and military dictators.

Sudan is key to the UAE’s strategy in Africa and the Middle East, aimed at achieving political and economic hegemony while curbing democratic aspirations. Since 2015, it has sourced mercenaries in Sudan to fuel its conflict in Yemen. It is the primary importer of Sudan’s gold and has multibillion-dollar plans to develop ports along Sudan’s Red Sea coast. They do not mind buying Gold from both warring parties, as NYT has receently reported, thus helping SAF to buy new weapons from Turkey, Iran, and Egypt, while they themselves deliver weapons and Chinese drones to the SAF.

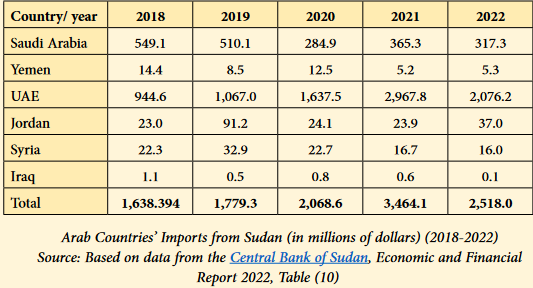

As the table published by Atar shows, the exports from Sudan have more than doubled after the revolution. These exports mainly went to the Emirates. The main export product, with 90% of the value, was gold.

In this war, UAE is on the winning side, anyway. The longer the war goes on, the higher the profits rise. SAF wants to sell gold and huge areas of land just like RSF. Both sides need the money, and pay with gold as well as with population murdered or displaced. For UAE, it is a good idea to keep the war going, until the land it cleared and the roots of democracy eradicated.

Paving the Way for RSF

In the months leading up to the war, UAE-affiliated networks intensified efforts to fortify RSF’s presence on social media, laying the groundwork for the militia’s des-information and misinformation campaigns. At the onset of the war, a Dubai-based expert team managed RSF’s media and propaganda, portraying the militia favourably to European decision-makers.

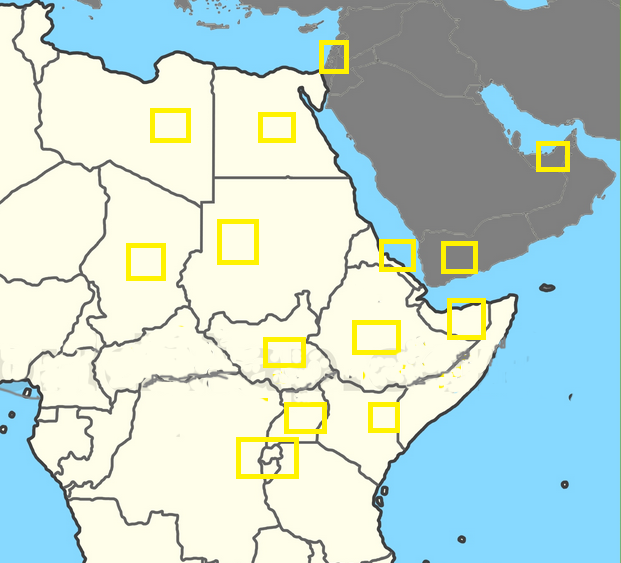

MBZ met with the leaders of Chad and Ethiopia, garnering support for the RSF, and paved the way for pompous visits by Hemedti in the countries of the „Belt of Bribes“ to which MBZ had payed billions for their cooperation. In December 2024, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemedti), the RSF commander visited six African countries on a “Victory Tour”, with an Emirati airplane belonging to a company owned by an Emirati royal and adviser to the president.

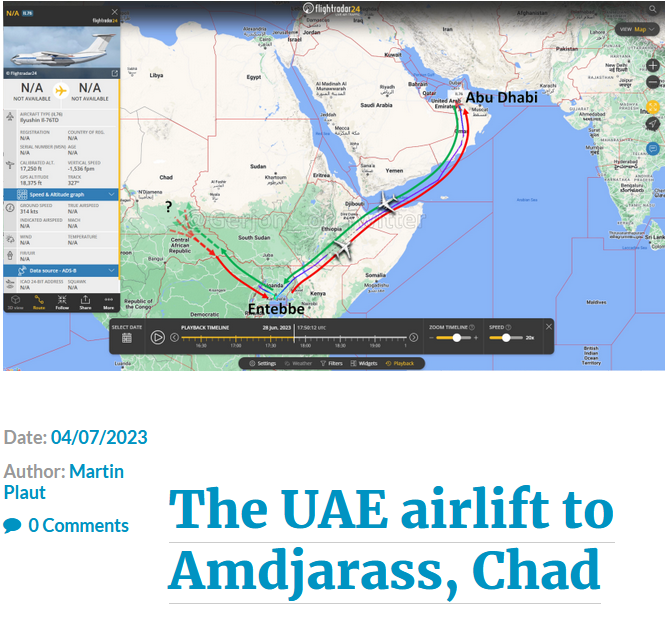

Especially „Flipping Chad“ was important for the logistics of the war. During summer 2023, the remote Chad town of Amdjarass had turned into a “boom town” at the border to Darfur. According to Succès Masra, a former prime minister of Chad, the Emirates promised the president of Chad, Mr. Déby a $1.5 billion loan, nearly as big as Chad’s $1.8 billion national budget a year earlier. The obvious aim: To allow the emirates sending weapons to the RSF via Chad. “It’s very clear: The U.A.E. is sending money, the U.A.E. is sending weapons,” he said according to the New York Times (21 Sept 2024).

This map shows where strongmen or warlords have been bribed by MBZ and his team. We call it the Belt of Bribes.

Upon the outbreak of war, UAE reportedly established logistical operations to send weapons to the RSF through its networks in Libya, Chad, Central African Republic, South Sudan, Uganda. The UAE also facilitated weapon shipments for the RSF through the Haftar and Wagner militias. “These extensive and sustained supplies ranged from small and light weapons to drones, anti-aircraft missiles, mortars and various types of ammunition,” according to a UN expert report 2023, citing sources among armed groups and tribal leaders in eastern Chad and Darfur.

The aforementioned airport of Amdjarass became the heart of an “elaborate covert operation” being run by the UAE to back the RSF, “supplying powerful weapons and drones, treating injured fighters and airlifting the most serious cases to one of its military hospitals”. Up until 30 September, the flight tracker Gerjon recorded 109 cargo flights coming from the UAE, stopping briefly at Entebbe in Uganda and then flying on to Amdjarass. (Gerjon has since deactivated their account following what they described as “a recent incident” which, they said, meant they “no longer feel safe”.) As flights from Uganda to Chad can be tracked, the RSF and its backers have been trying to bring cargo into Sudanese airspace, where it cannot be followed.

NYT has proved not only the delivery of arms to Amdjarass, but also that a drone system hat been established on the other side of the airfield. At the moment, RSF are attacking Al Fasher, the capital of Noth Darfur, and the last bastion of SAF in Darfur, with Chinese drones starting from there. Recently, French-made Galix defence system has been seen in RSF militia formations on armoured vehicles manufactured in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). This "Multi-Purpose Passive Self-Defence System for Land Platforms" also offers Grenades for "crowd management".

[Update: In April 2025 France 24 has published a series on European weapons in Sudan, about weapons from Bulgaria, delivered to RSF via the Emirates.]

RSF is recruiting mercenaries from the everywhere in the Sahel, and even contractors from Colombia. Often they are hired by UAE as security, and find themselves being dropped in Darfur. (There is a long history of Colombian mercenaries, hired by US enterprises.)

RSF as a Family Business

We have extensively written about the beginnings of the then Janjaweed in a previous blog entry. They were the perpetrators of the genocide in Darfur, in 2003, on behalf of the Islamist regime. Later, RSF also expanded it's business into protection money, drug trafficking, usurious loans and car theft. The war in Yemen brought even greater petrodollar profits from 2014 onwards, as Hemedti recruited thousands of young mercenaries for the then anti-Houthi alliance of Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

In November 2014 the EU initiated the Khartoum Process, and heavily relied on the RSF as a border guard. The EU supplied them with resources, but more than all with the international reputation of being an official Border Guard.

Hemedti's realm, RSF, is a family business like that of MBZ. The Daglo family became very wealthy thanks to the explosion of the gold price after 2007, as it controlled the extraction and the smuggling abroad of the precious metal from Darfur. In 2017, the RSF took over the Jebel Marra gold mine in Darfur, along with another three mines. Hemedti’s family company, Al Gunade, is in gold mining and trading, with stakes held by his brother Abdul Rahim Dagalo and two of Abdul Rahim’s sons. Hemeti is listed as a director, according to documents seen by the NGO Global Witness. Sudan today exports $16bn of gold to the UAE each year. Supporting Hemedti’s family business is much cheaper for the UAE than paying for a state with a hungry population.

More Info:

26.11.19 Reuters: Exclusive:Sudan militia leader grew rich by selling gold: Now a Reuters investigation has found that even as Hemedti was accusing Bashir's people of enriching themselves at the public's expense, a company that Hemedti's family owns was flying gold bars worth millions of dollars to Dubai.

Current and former government officials and gold industry sources said that in 2018 as Sudan's economy was imploding, Bashir gave Hemedti free rein to sell Sudan's most valuable natural resource through this family firm, Algunade. At times Algunade bypassed central bank controls over gold exports, at others it sold to the central bank for a preferential rate, half a dozen sources said. A central bank spokesman said he had no information about the matter.

09.12.19 Globalwitness: Exposing the RSF's secret financial network: An apparently genuine cache of leaked documents obtained by Global Witness show the financial networks behind Hemedti and the RSF. Not only have they captured a large part of the country’s gold industry through a linked company, but the leaked bank data and corporate documents show their use of front companies and banks based in Sudan and the UAE.

09.06.20 ECFR: Bad company: How dark money threatens Sudan’s transition: The United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia appear to be positioning a paramilitary leader known as Hemedti as Sudan’s next ruler, but the military is fiercely hostile towards him. Western countries and international institutions have let the civilian wing of the government down: they failed to provide the financial and political support that would allow Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok to hold his own against the generals.

10.11.21 Quantara: The UAE – pulling Sudanese strings: The Emiratis signalled early on their support for the toppling of Bashir in contacts with elements of the opposition and armed forces in 2019, at a moment when the military and paramilitary were mulling the removal of the president in a power grab. UAE officials assumed that the military and the RSF would emerge as the dominant force in a new Sudan. The Emirati foreign ministry stressed in a statement in the wake of the coup "the need to preserve the political and economic gains that have been achieved…

26.05.23 MC.Info: How the European Union finances oppression: The EU has time and again been accused of financing the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary structure in Sudan that has its roots in the militias that committed war crimes and genocide in Darfur. The EU denies this support and hard proof of direct support is rare. More important though, is to consider the logic and structures of the EU and European member states’ cooperation with Sudan in the area of migration and border control to understand the connection of the EU to the RSF. This connection, however, is far from simple to understand: It is concealed within multiple official and secret forms of cooperation.

29.09.23 NYT: Talking Peace in Sudan, the U.A.E. Secretly Fuels the Fight: From a remote air base in Chad, the Emirates is giving arms and medical treatment to fighters on one side in Sudan’s worsening war, officials say.

30.09.23 Phenomenal War: Marketing War: In one way, the crisis of the RSF began when the war in Yemen cooled down. Thousands of fighters came back to Sudan from Yemen, and they needed income, employment, and some level of insurance. These were all young people who still had years of fighting careers ahead of them. The RSF had to manage its cash economy in terms of its investments, and it needed to find a purpose for these fighters.

10.01.24 Roape: Exposing the murderers – the UAE involvement in the war in Sudan: In this long-read, Husam Osman Mahjoub examines the growing and profound influence of the UAE and Saudi Arabia in the region over the years, and Sudan in particular. He argues that war in Sudan drives the final nail into the coffin for the democratic aspirations of the peoples of the Arab and African region. Husam Mahjoub explains that understanding the positions and actions of these countries is crucial for appreciating and, more importantly, working towards stopping the war that erupted on 15 April last year between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

24.05.24 Guardian: It’s an open secret: the UAE is fuelling Sudan’s war – and there’ll be no peace until we call it out: The Emirates is arming and supporting one side in the conflict, but UK and US officials have shied from confronting it

10.07.24 Arabian Business: Inside the UAE’s business-first soft power diplomatic drive: The UAE’s business-first approach to diplomacy is not only securing its economic future but also reshaping the contours of global trade and international relations, experts say

12.08.24 Atar: Hassan Alnaser: Sudan and the UAE: The issue is not war: Economics of UAE RSF liaison, quoted extensively above

01.09.24 MEE: How Sudan's RSF became a key ally for the UAE’s logistical and corporate interests: Analysts say Abu Dhabi is exploiting the African country's resources at the expense of locals, using Sudanese militias with impunity. Experts and observers argue that part of the UAE's motivation for funding the devastating hostilities is to guarantee its access to Sudanese land, seaports, and mineral and agricultural resources, including livestock and crops.

21.09.24 NYT: How a U.S. Ally Uses Aid as a Cover in War: The United Arab Emirates is expanding a covert campaign to back a winner in Sudan’s civil war. Waving the banner of the Red Crescent, it is also smuggling weapons and deploying drones.

11.12.24 NYT: The Gold Rush at the Heart of a Civil War: Famine and ethnic cleansing stalk Sudan. Yet the gold trade is booming, enriching generals and propelling the fight.

21.12.24 African Arguments: How the UAE kept the Sudan war raging: A network of munition supply lines, backing the Rapid Support Forces against the Sudanese army, can be traced to the Gulf via Libya, Chad, Uganda and elsewhere.

Land Seizures in the History of Sudan

Militarisation of Agriculture

Climate change, increasing water scarcity, and spreading desertification have led to an agriculture in conflict mode, including conflicts between small peasants and agro-industry, as well as between peasants and pastoralists. This atmosphere of conflict has lead to to a militarised form of farming, from sowing, and harvesting, to export. In this process, the RSF has gained income and reputation as a Security actor, guarding farms, harvests, and cattle transports. The war in Darfur, 2003 – 05, was a strong driver in this militarization process.

Since the war in Darfur, Sudan has become the main supplier of fresh meat to the Gulf states. The mechanisation of Sudanese agriculture was accelerated by the vision of Sudan as a “breadbasket for the Arab region”, which was already in 2003 endorsed by the Gulf States. This vision, along with the Sudanese debt to the Gulf States, has increased the pressure to displace population, and increase productivity in the agrarian sector.

"The militarization of rural production is not limited to the war-ravaged regions of Sudan, but is now an integral part of rural life. A special security force, in which the RSF is also involved, is tasked with monitoring the harvest season, when armed gangs roam the countryside to capture the freshly harvested crops still waiting in the fields to be properly stored and transported. Even more far-reaching is the militarization of pastoral livelihoods. A driving factor was the increasing commercialization of pastoralism and the need to secure the treks of herds to export markets.“ Edward Thomas and Magdi el Gizouli (2021)

Land Seizures and Resistance

Throughout Sudanese history, there have always been social disputes over the issues of food security and access to, and use and control of, arable land. For a long time, the use of agricultural land was tied to traditional negotiation processes. Against the backdrop of the climatic conditions, a mixture of agriculture linked to the rainy seasons (millet, sorghum, wheat, etc.) and associated migratory livestock farming (sheep, camels, cattle, etc.) developed in many regions.

With colonialism and the post-colonial modernisation policies that followed, the state tried to give a legal status (property rights) for the disposal of land. In 1979, the Unregistered Land Act of 1970 was put into force. As a result of the subsequent modernization projects, there were frequent disputes with the respective regional residents or immigrants. All large agricultural farm projects and also the dam and irrigation projects could only be enforced by police and military means:

„This legal dispossession of unregistered lands, which account for 90% of all lands in the country, appears to be the most common form of expropriation in Sudan. Land seizures have been common in the states of South Kordofan and Blue Nile, and in the eastern region. The state has seized land and leased it out to private entities for development of large mechanized farming operations. The government has used gunships and helicopters to clear people from villages to secure land for the development of oil fields.“

The UAE was a lender to the Sudanese government already in the 1980s, and demanded repayment in the form of food exports. This was a strong driver for the modernisation of agriculture in Sudan. After 1989, in the times of international sanctions on Sudan due to Omar Al-Bashirs policy of genocide and backing terrorism, the UAE, though a western ally, didn’t care about these sanctions, and took over the monopoly as buyer of Sudanese exports. During the 30 years of that regime, many local Islamist investors got hold of a great part of the arable land. There was much resistance to this, especially by peasant union in Gezira, but also by peasant populations all over the country.

The genocide in Darfur in 2003 was a historical climax in that process of displacement. 300 000 were killed, and many thousands are living in refugee camps since then, in Chad and in Khartoum. The small herds and villages of the peasants and pastoralists were replaced by large and militarized ranches for cattle. Sudan became a large exporter of food and meat.

In May 2024, Nicholas Stockton, a former UN senior humanitarian adviser, published a short statement in the Guardian, how KSA und UAE could easily end the war in Sudan (It can be left aside here that the interests of KSA are slightliy different from UAE’s. KSA rather wants to pacify, and UAE has a more aggressive agenda. Note: Sudan’s exports to UAE are 7x higher than those into KSA):

„After decades of marginalisation, Sudan’s pastoralist herders started hitting back in 2003, destroying peasant farmers’ villages and converting the most favoured agricultural zones in Sudan into gigantic militarised ranches.

Since December 2023, the Rapid Support Forces have been repeating this process in Gezira, Sudan’s largest irrigated agricultural scheme. All this to take advantage of the burgeoning livestock trade with the Gulf states and Saudi Arabia, and now re-established as Sudan’s leading export industry.

This is the principal driver of Sudan’s civil war. The fastest and most effective way of stopping it would be to control this trade and thereby remove the incentives that underlie the brutal land clearances. Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states could stop the war in Sudan at a stroke by adopting ethical trade policies that exclude all livestock exported from Sudan’s killing fields.“

Source: GIGA 2018

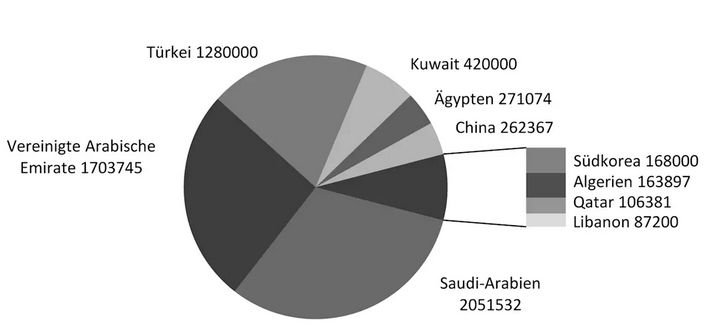

For Sudan, the years after the Darfur genocide were prosperous years. However, in 2011, Sudan lost the oil fields to Suoth Sudan, and the state went near bankrupt. Now the Islamists had to sell the land to foreign investors. As the diagram from GIGA (2018) shows, the Gulf states were the main profiteers, besides Turkish investors.

As the GIGA autors wrote, the concessions of this time had roughly the size of Austria, more than 8 million hectares. And they noted that

“A large proportion of the released land was previously used by small farmers or pastoral groups, who were deprived of their livelihoods as a result of the expropriations. The result is a sometimes violent backlash. In the country's conflict regions, there is a risk that the losers of the land investments will join violent groups.”

After the revolution, the state was under pressure of IMF and Creditors from the Gulf states, and was forced to pay the debts of the Bashir regime. So one solution for them was to sell even more land, besides gold, and agricultural products.

However, when the process of the Revolutionary Charter spread across the countryside, this process also fostered the resistance of the peasants to the expropriation of their plots. Breaking the resistance against this sell-out of the country was, as we think, one of the deep reasons to make war against the Sudanese population: against the Resistance Committees in the cities, but also against peasant and pastoralist resistance against the sale of their land.

In 2020, there was a remarkable incident, regarding the Al-Fashaga region, which was under dispute between Sudan and Ethiopia. This incident sheds a light on the genesis of the conflict between SAF and RSF, but also on the Emirate’s way of solving conflicts. We quote from Hassan Alnaser, in: Atar, 12.08.24:

The underlying conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the RSF is fundamentally economic, centred on their relationship and trade dynamics. The military confrontation with Ethiopia in the Al-Fashaga region is a prime example. On September 6, 2020, the SAF attempted to reclaim Al-Fashaga, which had been occupied by Ethiopia since 1991, taking advantage of Ethiopia’s preoccupation with its internal conflict against the Tigray forces.

[...]

Hemeti did not directly intervene in the Al-Fashaga issue, except by supporting a UAE initiative to resolve it. This proposal suggested that the SAF withdraw to pre September 2020 borders, with the UAE investing in Al-Fashaga’s land, distributing returns as 40 per cent to Sudan, 40 per cent to Ethiopia, and 20 per cent to the UAE.

The Al-Fashaga issue marked a turning point in the relationship between the SAF and the RSF.

More Info:

Sept. 2016 Sudan Democracy First Group: Land Use, Ownership and Allocation in Sudan (PDF): The first part of this research focuses on the spatial impact of resource-extracting economies, notably the foreign acquisitions of agricultural land. The case studies from South Kordofan/Nuba Mountains, Blue Nile, Northern and River Nile states and Eastern Sudan, show how rural people experience "their" land vis-à-vis the latest wave of privatization and commercialization of land rights. The second part of this research will address and analyze lack of transparency and corruption in the field of land use, ownership and allocation.

2017 Consilience: Land Grab and Institutional Legacy of Colonialism: The Case of Sudan: Over last decade Africa has experienced an unprecedented amounts of land being concessioned, leased or sold to business, corporations or foreign sovereign capital. The land question (who can acquire or have access to land) and the political question (who belongs in the political community) are connected to the citizenship question. These questions are among the most politicized in Africa.

The first section of this article discusses and provides the intellectual background that informs today’s land rush. The second section discusses the competing actors involved in the land grab, winners and victims. Here I will argue that the majority of victims of land dispossession in the African context are peasants, pastoralists, nomadic, and trans- boundary communities, whose land management system is based on customary land tenure.

2018 GIGA: Brotkorb und Konfliktherd – Landinvestitionen in der Republik Sudan: Kaum ein anderer Staat verfügt über größere landwirtschaftlich nutzbare Flächen als der Sudan, jedoch droht eine Zunahme internationaler Landkäufe, bestehende Konflikte zu verschärfen. Schätzungen zufolge hat die sudanesische Regierung seit dem Jahr 2011 Konzessionen mit einer Gesamtfläche von mehr als acht Millionen Hektar an nationale und internationale Investoren erteilt – das entspricht ungefähr der Größe Österreichs.

Ein großer Anteil der freigegebenen Landflächen wurde zuvor von Kleinbauern oder pastoralen Gruppen genutzt, denen die Enteignungen die wirtschaftliche Lebensgrundlage entzieht. Die Folge sind teils gewaltsame Gegenreaktionen. In den Konfliktregionen des Landes besteht das Risiko, dass sich die Verlierer der Landinvestitionen gewaltsamen Gruppierungen anschließen.

Die Investitionen der UAE belaufen sich auf 1,7 Millionen ha bis 2017. UAE ist nach KSR (2 Millionen ha) der zweitgrößte Investor.

July 2023 Insecurity insight: The Sudan Crisis, Conflict and Food Insecurity: This briefing discusses specific conflict incidents with clearly foreseeable consequences for civilians and civilian objects necessary for achieving food security. In doing so, it aims to help break the vicious cycle between armed conflict and food insecurity

03.07.24 Grain: From land to logistics: UAE's growing power in the global food system: In the pursuit of its own food security, the UAE, like other Gulf states, has been getting control of land to develop farm operations in Sudan. Right now, two Emirati firms –International Holding Company (IHC), the country’s largest listed corporation, and Jenaan – are farming over 50,000 hectares there. In 2022, a deal was signed between IHC and the DAL group – owned by one of Sudan’s wealthiest tycoons – to develop an additional 162,000 ha of farmland in Abu Hamad, in the north. This massive farm project, backed by the UAE government, will connect to a brand-new port on the coast of Sudan to be built and operated by the Abu Dhabi Ports Group. The economic stakes around this project are mammoth. But so are the political ones. The current port of Sudan, which the project will completely bypass, is run by the Sudanese government.

12.08.2024 Atar:Sudan and the UAE: The Issue is not war: A good Short History about Sudan and UAE investment interests

(C) Toshi Takamizawa

Characteristics of the UAE

Up to the 2000s, the Emirates were a junior partner of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and followed that kingdom in many respects. Since the rise of the new Emir, Mohamed bin Zayed (MBZ) in 2004, the Emirates have more and more pursued their own reckless policy of investment and war. After 2011, faced with the Arab Revolution and the uprising in Bahrain, and given their high dependency on migrant labour, the Emirs have pursued a consistently counter-revolutionary course, which was not only directed against the aspirations of the rebellious populations in the neighbouring countries, but also against religious radicalisation.

A study by the SWP in 2020 names these characteristics of the UAE's foreign policy:

- The Emirates see the Muslim Brotherhood and it’s allies as a threat, because of their appeal to the lower classes. They like to ally themselves with autocratic regimes that oppose the Muslim Brotherhood and political Islam.

- The Emirates oppose Iranian expansion, but consider Sunni Islamism to be the greater threat.

- Since the start of the Yemen war in 2015, the Emirates have been endeavouring to gain maritime control of the Red Sea and are developing into a regional power.

But a closer look indicates that their fear of democratic movements in the region precedes all these considerations. As Mahjoub (2024) writes,

„For KSA and the UAE, the Arab Spring posed an existential threat to their ultra-conservative monarchies, built on clan and tribal foundations, suppression of freedoms, inequality, discrimination, and military reliance on the United States“.

The Emirs (and their allies) regard democracy as a threat to their power and investments. They have supported militias, killing thousands via mercenaries in Libya, Yemen and Sudan, without having to answer to any authority. Their model of capitalism without democracy – the dream of unchallenged accumulation and wealth – is highly attractive for right-wing policy all over the world. The winner takes it all.

2007 was the year of the big financial crisis, but also a year of rising food prizes, which lead to hunger revolts all over Africa. Since then, UAE have switched their investment from financial assets to real and tangible value, like ports, real estate, land and gold.

Also, since 2007, the Emirs are aware of the strategic importance of food security. After a failed agricultural program at home, they have invested big scale in agricultural schemes in Egypt, Sudan and other countries, not only in order to secure the alimentation of their foreign workforce, but also processing food and diary products for export. The strategic relevance of Sudan is obvious, as 80% of the food consumed or processed in UAE come from this country.

Leading over to the Emirate’s Investment Strategies, the following characteristics should be added:

- Like KSA, the Emirates are pursuing the goal of diversifying their economy and becoming independent of fossil fuel exports.

- The Emirates have highly equipped armed forces, but prefer to have mercenaries and proxy militias fighting for their interests - an approach that proved its worth in the Yemen and Libya and has now been resumed in Sudan.

- The "multipolar world order" gives regional centres of power more leeway. In this context, the Emirates feel emboldened to ruthlessly assert their regional interests. They see themselves strong enough to defend their strategic investments. UAE are advancing as a maritime power and as a marketing hub of African resources.

- Dubai is the biggest humanitarian hub of the world. Maritime and commercial power goes hand in hand with military and humanitarian interventions.

- The Emirates' economy is fuelled by the exploitation of 9 million immigrant workers, primarily from South Asia. The internal security apparatus naturally serves first and foremost to maintain the power of the ruling families, but at the same time to maintain a racially differentiated labour market through recruitment and deportation, and to prevent the working class from protest and organizing itself.

UAE Investment Strategies

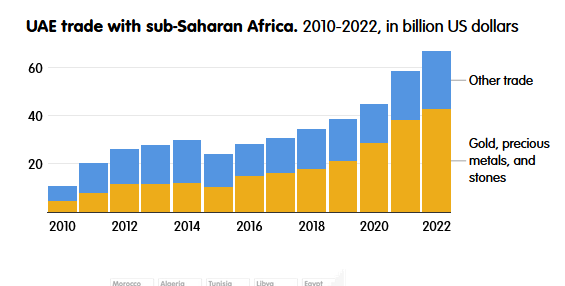

Over the past decade, the UAE has become Africa’s fourth largest foreign investor, behind China, the EU and the US. Between 2012 and 2022, the UAE injected $60 billion into the continent in infrastructure, energy, land aquisition, telecommunications, and transport.

In March 2024, the Secretary General of the UAE International Investors Council (UAEIIC), Jamal Bin Saif Al Jarwan , proudly announced that the Emirates had cemented its position as a leading regional and global player in foreign direct investment. He estimated that the total value of Emirati investments abroad, spanning both the government and private sectors, would reach a staggering 2.5 trillion US-$ (2.500.000.000.000) across 90 countries by early 2024. He also expressed the expectation of interest in Emirati investment in countries such as India, Indonesia, ASEAN, Egypt, Morocco and others, including some European countries and Turkey.

In this section, we are sharing information about four fields of investment:

- Logistics and Trade, including Humanitarian Logistics,

- Minerals and Gold,

- Food Security and Land-Grabbing,

- and Renweable Energy.

Logistic and Trade

The UAE are one of the most important actors of global logistics: They run a network of state-owned companies, especially Dubai Ports World, which controls 87 ports in 40 countries worldwide, and the Abu Dhabi Ports Group, with a strong presence in East Africa (Tanzania, Somaliland, Mozambique, Sudan, Djibouti, Puntland), but also in Rwanda, Congo, Angola, Senegal, Guinea as well as in South Africa, Algeria and Egypt). Also they run the Etihad and Emirates airlines, and position themselves centrally in international supply chains and global commodity flows.

A map of the ports of DP World and Abu Dabi Ports can be found on ECFR (2024). Also they write about DP World:

DP World’s existing portfolio in Africa includes SEZs, railway and transport services, dry ports and logistics venues, and even e-commerce, as well as a recent acquisition of South Africa’s Imperial Logistics and Nigeria’s Africa FMCG Distribution, making DP World’s logistics network widespread across the continent.

Source: ECFR (2024)

The diagram, from the same source, shows that the trade with Subsahara Africa has been rapidly increasing during the very last years. This is partly due to the soaring gold price, but also the trade with non-mineral products, mainly unprocessed food, as UAE import more than 85% of their food.

There is a strong link between the chain of Ports around Africa, and the projection of power. An article which was recently published in the IPG journal, sais:

“Granted, a business approach is key to UAE engagement, especially through state-owned enterprises. Dubai Ports World (DP World) and AD Ports Group (ADP) act as beachheads, operating 13 ports in eight African countries, with six new deals signed in the past four years. They also run a vast network of transport infrastructure, including railways and dry ports. […]

Hence, there is a clear spill-over effect from port/infrastructure projects into defence and security partnerships. This is true for many African countries, where DP World and ADP projects have been followed by arms exports, defence industry deals, or military and police training agreements.”

The DIHC (Dubai International Humanitarian City) is part of DP World, a network of UN Humanitarian Response Depots with locations in Ghana, Italy, Malaysia, Spain and Panama, which manage the supply chains of emergency items for UN agencies and NGO partners. The strategic concept of linking military, humanitarian and trade logistics is currently visible in the support for the RSF, with the combination of military and humanitarian transports, via Uganda and Chad. We have described this above.

In the Yemen war, 2015, the Emirates did the same thing. A report on MERIP (2019) states:

A focus on the multiple concurrent forms of intervention by states like the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which boasts the world’s largest humanitarian hub, illustrates the role humanitarian logistics can play in amplifying and projecting military power. As the most aggressive partner in the Saudi-led coalition fighting in Yemen, the UAE’s military intervention includes a clear strategy to control Yemeni ports on the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea, alongside the primary maritime trade route between Asia and Europe and a major chokepoint in global shipping, the Bab Al Mandeb passage at the intersection of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. Three ports—Mukalla, Aden and Mokha—as well as the island of Socotra and an oil export terminal located in the eastern coastal city of al-Shihr, have all come under UAE control.

Alongside the occupation and control of these ports, the UAE has employed humanitarian aid as a tool to distract attention from its ongoing military campaign, with Emirati aid agencies inviting journalists to accompany them while distributing supplies to areas under their military control. Indeed, although Yemen has become the largest recipient of all UAE foreign and humanitarian aid, this funding is increasingly aimed at supporting infrastructure projects that link Yemen’s ports to regional shipping routes.

Strategic Commodities

The United Arab Emirates aree one of the largest export markets for African gold producers, with around 34 billion dollars worth of gold from across the continent making its way into the country in 2022. Data are presented in ECFR (2024).

The Emirates have mining investments in Angola, DRC, Guinea, Mauritania, Nigeria, South Africa and Zambia, and are in negotiation with Burundi, Kenya, and Tanzania. At the same time they act as a legalisation gateway for illegal gold. This gold not only comes from Darfur, but also from artisanal mines across the Sahel and Subsaharan Africa.

The metals required for the “Green New Deal” are another focus of UAE interest. Their alley in Rwanda, Kagame, is at the moment waging war in Kivu, thus securing the transports of the precious metals to the UAE, via Kigali.

Food Security, Land Grabbing

Since 2008, the UAE has played an increasingly important role in the purchase or long-term leasing of land. They have already signed 56 land agreements in Africa, and there are 14 more deals in the pipeline. This is just one example:

In July, Dubai Investments and E20 Investment, an Abu Dhabi agribusiness investment company, signed a deal to develop a vast plot in Angola. The partners aim to produce 28,000 tonnes of rice and 5,500 tonnes of avocados over the next 18 months on the land, which is the size of 9,300 football fields.

Reuters reported in November that Al Dahra, an Emirati agribusiness firm, was in talks with Egypt to buy or lease land in Toshka under a long-term agreement with the intention of cultivating staple grain crops.

The United Arab Emirates, a country that has almost no ecological basis for large-scale agriculture, has an agricultural export value which is now greater than that of Egypt. In 1991, food exports from the UAE amounted to 9.4 million dollars; in 2021, these had soared to 14.9 billion dollars, which is the highest export ratio in the Arab world.

The Green Deal

On the recent COP 29 conference in Baku, UAE were a strong backer of "fossil fuels vow". In opposition to KSA, they see Green Colonialism as an immediate field of interest. Between 2019 and 2023, Emirati companies announced $110bn (£88bn) of projects, $72bn of them in renewable energy. There are investments in Renewables all over Africa, including Batteries, Solar, Hydrogen, Wind and Thermal, as is shown on a map by ECFR.

Another field of investment, in the same context, is the commodification of forests. With the perspective of certificate trading, UAE have acquired huge areas of forest, with the size of Britain.

Since 2022, the Dubai royal Sheikh Ahmed Dalmook al-Maktoum has struck deals to sell carbon credits from forests covering a fifth of Zimbabwe, 10% of Liberia, 10% of Zambia and 8% of Tanzania.

This goes hand in hand with clearing the forests from populations, and establishment of prime Safari tourism. In Tanzania, UAE have been under scrutiny by various human rights groups for violently displacing the Maasai population out of their ancestral land to give way to a wildlife corridor for trophy hunting and elite tourism, utterly disregarding the Indigenous people’s rights to their traditional livelihood. Amnesty has reported on mass arrests and brutal forced evictions. In total, almost 150,000 Maasai people are facing displacement.

More Info:

Spring 2019 MEIRIP: The UAE and the Infrastructure of Intervention: A focus on the multiple concurrent forms of intervention by states like the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which boasts the world’s largest humanitarian hub, illustrates the role humanitarian logistics can play in amplifying and projecting military power. UAE has employed humanitarian aid as a tool to distract attention from its ongoing military campaign, with Emirati aid agencies inviting journalists to accompany them while distributing supplies to areas under their military control. (This is about Yemen)

Fall / Winter 2019 MERIP: Regional Uprisings Confront Gulf-Backed Counterrevolution: Watching the events of 2011 with growing alarm, the rulers of Saudi Arabia and the UAE embarked upon a regional counterrevolution. They helped stamp out an uprising in Bahrain, intervened in Yemen’s post-uprising transition and undercut Egypt’s revolution in 2013 by backing the military coup that led to the ascent of Abd al-Fattah al-Sisi as Egypt’s newest president for life. Not only did their intervention in Egypt help overthrow an elected Muslim Brotherhood government supported by regional rivals Qatar and Turkey, but it also ensured the failure of Egypt’s democratic transition. Saudi Arabia and the UAE have showered Egypt’s military regime with billions of dollars of aid in order to secure their desired vision of regional order that places severe limits on political opposition. Although small protests in September 2019 challenged Egypt’s military rule, the “Sisi model” effectively serves as the template that Saudi Arabia and the UAE have sought to impose across the region.

08.07.20 SWP: Regional Power United Arab Emirates: Abu Dhabi Is No Longer Saudi Arabia’s Junior Partner: Since the Arab Spring of 2011, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have been pursuing an increasingly active foreign and security policy and have emerged as a leading regional power.

Nov. 2020 Thesentry: Understanding Money Laundering Risks in the Conflict Gold Trade From East and Central Africa to Dubai and Onward: The record-breaking rise in world gold prices in recent years has driven a new artisanal gold mining and refining rush in conflict-affected and high-risk areas in East and Central Africa. Annually, over $3 billion in gold mined in the affected regions, including conflict gold from which armed groups and army units profit, reaches international markets in the United States, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East,7 according to investi-gations by The Sentry and other organisations.

Nearly all of this gold is first imported to Dubai, UAE, which has rapidly risen over the past 20 years to become one of the world’s largest gold trading centres, particularly for artisanal and small-scale gold from sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and South Asia. 9 Artisanally mined gold from the DRC, South Sudan, and CAR is mainly smuggled or exported to one of six neighboring countries—Uganda, Rwanda, Cameroon, Kenya, Chad, or Burundi—before being exported to Dubai. Sudan mainly exports directly to the UAE.

10.08.23 SWP: Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the UAE: The End of an Alliance: Over the past 10 years, the de facto alliance of the governments of Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates has exercised significant influence over developments in the Middle East. The common goal has been to prevent democratic transformation, stop the rise of political Islam and counter the influence of Iran and Turkey over the region. But joint regional political interventions have so far had little success. Moreover, divergences of interest in bilateral relations between these authoritarian Arab states have come to light in recent months. The potential for conflict has become evident with regard to both economic and regional political issues and is only likely to increase in the future.

31.01.24 AGBI: UAE in talks to buy more African land to aid food security: The UAE has 14 land acquisition deals in the pipeline, mainly in Africa, as it looks to keep food security high on its policy agenda. It has already signed 56 land agreements, with the first completed more than 50 years ago in Sudan.

19.03.24 WAM: UAE investments abroad hit $2.5 trillion in beginning of 2024: Jamal Bin Saif Al Jarwan, Secretary-General of the UAE International Investors Council (UAEIIC) explained that the UAE is a leading investor in Egypt with around 2,000 Emirati companies across various sectors such as telecommunications, real estate, oil and gas, agriculture, and more. Al Jarwan highlighted the global strategic interest in UAE investments due to positive factors, confidence in UAE leadership, and professional investors.

He mentioned operating in 90 countries and expressed expectations for interest in investments from countries like India, Indonesia, ASEAN nations, Egypt, Morocco, and others, including certain European countries and Turkiye.

29.05.24 NLR: Colin Powers: Capital’s Emirates: At first glance, the United Arab Emirates, an oil-rich monarchy with a long history of loyalty to American empire, appears to be adapting to the multipolar order. Since 2022 it has recused itself from Washington’s economic war on Russia. Abu Dhabi, the emirate responsible for the federation’s foreign and energy policy (and the one sitting on most of its oil reserves), has blocked the exclusion of Russia from OPEC+ monthly quotas. Dubai, the region’s major freight centre, exports Russian-bound drones and semiconductors, while allowing Russian-originating bullion and diamonds to pass through its Gold & Commodities Exchange. The city’s property market and docks have been made available for Russians who need a place to hide their wealth.. The UAE also provides invaluable services to another American foe: Iran. And then there is China, now the largest buyer of goods made in or transiting through the UAE. Roughly two-thirds of all Chinese exports to the Middle East, Africa and Europe pass through Emirati ports.

But the Emirates’ motivations are more complex than mere sovereigntism. On closer examination, many of their recent actions can be understood as respecting, rather than renouncing, obligations to empire. Despite partnerships with nonconforming states, the country remains committed to US-led neoliberal globalization: a faithful servant of what Ellen Meiksins Wood called the ‘empire of capital’.

For a different view, see NYT 08.08.23: An Oil-Rich Ally Tests Its Relationship With the U.S.: The United Arab Emirates, which has translated its wealth into outsize global influence, is diverging from U.S. foreign policy — particularly when it comes to isolating Russia and limiting ties with China.

30.11.23 Guardian: The new ‘scramble for Africa’: how a UAE sheikh quietly made carbon deals for forests bigger than UK: Agreements have been struck with African states home to crucial biodiversity hotspots, for land representing billions of dollars in potential carbon offsetting revenue

30.11.23 Guardian: Who is the UAE sheikh behind deals to manage vast areas of African forest?: Through the firm Blue Carbon, Sheikh Ahmed Dalmook al-Maktoum’s carbon offsetting deals, which could one day be worth billions, have led to questions about previous business ventures. Through the United Arab Emirates-based company Blue Carbon, the sheikh’s deals cover a fifth of Zimbabwe, 10% of Liberia, 10% of Zambia and 8% of Tanzania, collectively amounting to an area the size of the UK – and more are expected.

17.04.24 WPR: The UAE Has Set Its Sights on Africa’s Critical Minerals: The United Arab Emirates is rapidly emerging as a major player in the mining sector in Africa. The country is already a hub for the licit and illicit trade in gold and gemstones from across the continent. Its new targets are mines producing metals that are key to the green transition to low-carbon energy sources. With its oil-dependent economy vulnerable to the global shift away from fossil fuels, Abu Dhabi is trying to secure a central place in the new energy economy.

29.05.24 Africa Report: UAE: DP World makes a play for Africa: The Dubai-based logistics giant is both a thriving business and a geopolitical soft power tool. Today the company employs more than 20,000 people across the continent. It operates ports and logistics centres in nine African countries – Algeria, Angola, Djibouti, Egypt, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal and South Africa – as well as the self-declared state of Somaliland.

20.06.24 ECFR: Beyond competition: How Europe can harness the UAE’s energy ambitions in Africa: Since 2020, the UAE has strategically expanded its involvement in Africa, marking a significant shift in its foreign policy and becoming an influential middle power on the continent. European countries should pursue a strategy of “co-opetition” towards the UAE, balancing competition in areas in which they have comparative advantages with cooperation in areas of mutual interest.

(Extensive Article with diagrams and maps on UAE projects in Africa.)

03.06.24 Africa Report: Ports, farmland, contracts: What is UAE’s Mohamed bin Zayed seeking in Africa?: Over the past decade, the UAE has become Africa’s fourth largest foreign investor, behind China, the EU and the US. Between 2012 and 2022, the UAE injected $60bn into the continent in infrastructure, energy, agro-food, telecommunications and transport.

The petrol-driven monarchy has become a key player in the Horn of Africa and several other African countries. For Eleonora Ardemagni, a Middle East expert at the Italy-based ISPI, the UAE is “the only country capable of competing with China in both East and West Africa”.

Summer 2024 MERIP: Extractive Agribusinesses—Guaranteeing Food Security in the Gulf: Today GCC states—which import around 90 percent of their food—rank among the world’s highest in terms of food security and affordability, on par with many OECD states. Their citizens spend a relatively low share of their income on food.According to the Land Matrix database, between 2000–2022, Gulf states acquired more than two million hectares of agricultural land abroad.[4] Over a third of it was in other Arab countries. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar and Kuwait acquired some half a million hectares in Sudan. Egypt is another site of significant Gulf purchases at 157,851 hectares.

03.07.24 Grain: From land to logistics: UAE's growing power in the global food system: In the pursuit of its own food security, the UAE, like other Gulf states, has been getting control of land to develop farm operations in Sudan. Right now, two Emirati firms –International Holding Company (IHC), the country’s largest listed corporation, and Jenaan – are farming over 50,000 hectares there. In 2022, a deal was signed between IHC and the DAL group – owned by one of Sudan’s wealthiest tycoons – to develop an additional 162,000 ha of farmland in Abu Hamad, in the north. This massive farm project, backed by the UAE government, will connect to a brand-new port on the coast of Sudan to be built and operated by the Abu Dhabi Ports Group. The economic stakes around this project are mammoth. But so are the political ones. The current port of Sudan, which the project will completely bypass, is run by the Sudanese government.

19.07.24 ADHRB: The United Arab Emirates’ unethical foreign policy in Africa: The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has emerged as a significant player on the African continent, leveraging its economic and strategic initiatives to deepen its influence, involving investments in infrastructure, ports, and telecommunications, alongside military engagements and political alliances. However, UAE’s presence is not without controversy, particularly regarding allegations of neo-colonialism and human rights abuses, which cast a shadow over its intentions.

23.07.24 Ispionline: Minerals (also) for Defence: Unlocking the Emirati Mining Rush: The UAE is heavily investing in the mining sector in Africa and Latin America to adapt to the energy transition towards renewables and achieve national industrial goals. Mining deals allow the UAE to cope with the energy transition towards renewables and develop national industrial goals. There is something, however, that distinguishes the UAE from its Gulf neighbours. Abu Dhabi is developing its national defence industry and advanced defence technologies well ahead of Saudi Arabia.

01.10.24 Africa Report: UAE gold refiners suspected of handling illegally mined African gold: The suspicion of UAE processing illegally mined gold has led key gold traders, such as Swiss company, Metalor Technologies, to refuse to handle gold refined in the UAE.

Industry regulators, industry bodies and international market overseers now face the challenge of imposing strict diligence standards on the UAE refineries, which will have implications for African miners of gold in war-torn and unstable countries.

The proceeds of the sales in funding criminal groups, which includes buying arms and for corruption, were exposed in 2020 when Global Witness alleged that UAE-based Kaloti bought gold through an intermediary which in turn bought it from mines in Sudan’s Darfur region controlled by violent groups.

24.12.24 Guardian: UAE becomes Africa’s biggest investor amid rights concerns: The United Arab Emirates has become the largest backer of new business projects in Africa, raising hopes of a rush of much-needed money for green energy, but also concerns that the investments could compromise the rights of workers and environmental protections.

06.02.25 IPG: Arabische Scheckbuchdiplomatie: Die Vereinigten Arabischen Emirate sind heimlich zum größten Investor in Afrika aufgestiegen. Ihr Einfluss reicht weit über die Wirtschaft hinaus. (Extensive survey article)

Inside UAE: The New Dystopia

Workers Under Constant Threat: the Labour Market in the UAE

In the oil crisis of 1974, the Gulf States were actors in an epochal attack on the European working class. We have pointed out the role of petrodollar recycling. At the same time, the Emirates were also an actor in a new, post-national utilisation of mobile labour. As early as 1975, 64% of Emirati residents were non-nationals, and their share has grown steadily since then. In 2016, almost 90% of the 9 million residents were less-entitled foreigners. According to “le monde diplomatique” (1/2023) the population in UAE is composed as follows: 10% are Emiratis, 30% other Arabs or Iranians, 50% Southeast Asians and 10% Westerners (they do not mention Non-Arab Africans).

There are huge differences between the Westeners and the vast majority of exploited workforce. People from Asia and the WANA region are predominantly employed in low-skilled jobs, while highly skilled workers are mainly recruited from the USA and Europe. Labour migrants from Sudan and the WANA region, who have a language advantage over workers from Asia, are largely employed in the army, the police and the public sector. Women are only a small part of the migrant labour force. They work largely in private households and are particularly exposed to dependence on their employers through the kafala system. In 2014, the International Trade Union Confederation estimated the number of enslaved domestic workers in the Gulf States at 2.4 million. They mainly came from India, Sri Lanka, the Philippines and Nepal.

The Emirates reformed their labour law in 2017 and brought the status of employees in private households in line with general labour law. Meanwhile, there are tens of thousands of illegalised workers, including many who have fled the Kafala system and people who work on tourist visas and as visa overstayers and are mercilessly at the mercy of their bosses.

For the majority of the workers from Southeast Asia, the wages are low, housing is precarious, and access to health service is highly expensive. The broshure by Vital signs (2022), has published a few interviews with low-paid workers, like the following:

K.W. described crowded living quarters with eight to fifteen men sharing a room, and three toilets and two baths for sixty men, twelve hours of work, six days a week for salaries of 1150 dirhams (US $313) rather than the 2400 dirhams (US $653) promised.

Another worker on medical care:

The person who arranged my visa and tickets advised me to take Panadol, and Brufen [Ibuprofen] to Dubai because they are often needed and difficult to obtain in Dubai. We always requested someone arriving from Pakistan to bring medicines

along with him. Everyone had their own medicines in the labor camp.

The ‘offshore citizens’ are controlled via their ‘permanent temporary status’. Work visas are usually ‘sponsored’ by institutions or companies; better-off workers can ‘sponsor’ a family reunion. After dismissal, workers have 6 months to look for a new job before they are deported. Unauthorised protests are punishable by law.

Worker exploitation and European gas supplies go hand in Hand. A Climate Home News investigation found in 2022, that, while migrant workers building a major gas expansion in the UAE to supply Europe with energy alternatives, these workers face harsh conditions and a lack of transparency when risk turns deadly.

In 2023, The Guardian reported on the combination of worker exploitation and Climate talks: Migrant workers in Dubai had to work in dangerously hot temperatures to get conference facilities ready for world leaders attending this year’s Cop28 climate talk, despite of a summer-work ban.

“The economic engine that allows the prolific construction of luxury high rises and the survival of the conference and tourism-centred economy in Gulf countries is south-east Asian migrant workers, who in many cases have already been forced to flee the crippling economic and social impacts of climate change in their own countries,” said Amali Tower from Climate Refugees.

The Emirati themselves - unless they belong to the stateless Bidun minority, which makes up a quarter of the local population - have so far largely favoured well-paid positions in the public sector. In Vision UAE 2031, the state has been trying, with rather moderate success, to persuade them to take up employment in the private sector (‘Emiratisation’).

More Info:

Cave 2013! 18.09.13 MPI: Labor Migration in the United Arab Emirates: Challenges and Responses: With immigrants, who come particularly from India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, comprising over 90 percent of the country's private workforce, the UAE attracts both low- and high-skilled migrants due to its economic attractiveness, relative political stability, and modern infrastructure

Cave 2015! 17.03.15 Guardian: The global plight of domestic workers: few rights, little freedom, frequent abuse: A quarter of the world’s 53 million domestic staff have no labour rights, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation, beatings and sexual assault

Cave 2016! 06.07.2016 MigrationInstitute: Managing migrant labour in the Gulf: Transnational dynamics of migration politics since the 1930s: The politics and the economics of migration management evolved over time, accounting for instance for a shift in the geography of labour import – from Arab migration to Asian migration. Since the 1990s however States and governments have sought to increase their control in the management of migration as migrants’ settlement emerged as a security concern in Gulf societies. Reforms adopted in the wake of the Arab Spring have further illustrated this trend, bringing the State back in the illiberal transnationalism of migration management and anti-immigrant policies.

Book by Noora Lori 2019: Offshore Citizens. Permanent Temporary Status in the Gulf:

Chapters:

1 - Limbo Statuses and Precarious Citizenship

2 - Making the Nation: Citizens, “Guests,” and Ambiguous Legal Statuses

3 - Demographic Growth, Migrant Policing, and Naturalization as a “National Security” Threat

4 - Permanently Deportable: The Formal and Informal Institutions of the Kafāla System

5 - “Taʿāl Bachir” (Come Tomorrow): The Politics of Waiting for Identity Papers

6 - Identity Regularization and Passport Outsourcing: Turning Minorities into Foreigners

November 2022 Vital Signs: The Cost of Living: Migrant Worker's Access to Health in the Gulf(PDF): This report examines the specific issue of migrant workers’ access to healthcare in the Gulf, focusing again on workers in low-paid sectors of the economy.

Wikipedia: Migrant workers in the United Arab Emirates: In 2019, the UAE had the second-largest international migrant stock in the world at 87.9% with 8.6 million migrants (out of a total population of 9.8 million). Non-citizen, migrant workers, account for 90% of its workforce.

Security and Military

How can a „country“ with 1 million „citizens“ and 9 million foreign workers hold stability? And how can regional military dominance be executed?

The answer lies to a big part in in the efficiency of the security apparatus. which in itself employs foreign labour. There are thousands of police officers and military personnel, Pakistani or Sudanese migrants in the lover ranks, and US and European advisors in the higher ranks. And all of the foreign security forces will be disposed of after retirement.

Le Monde Diplomatique wrote about the UAE’s high-tech toolkit for mass surveillance and repression in January 2023:

‘Emiratis are a minority in their own country,’ says Andreas Krieg , a security specialist at King’s College, London. ‘Surveillance technology allows them to be omnipresent.’

The people I spoke to recognise that mass surveillance impinges on freedom of expression. Many preferred to discuss sensitive topics face-to-face rather than on the phone. ‘We assume — or rather, we know — that we are under constant surveillance, and that it’s dangerous to say anything politically sensitive, even on WhatsApp,’ said a European expatriate who asked to remain anonymous.

‘The 9/11 attacks were a turning point. They led to a rejection of all forms of political Islam, and tighter surveillance of mosques.’

The UAE, which relies extensively on foreign labour, also changed its policy on migration. The second explained that ‘until then, the UAE had welcomed large numbers of migrant workers from Arab countries. After 9/11, background checks were stepped up, especially for preachers and teachers. Migrants from Southeast Asia are considered less dangerous, and find it easier to get visas.’

The UAE's authoritarian agenda abroad reflects how tightly it controls politics at home, suppressing any form of opposition or dissent. Activists, journalists and ordinary Emiratis who dare to speak out against the regime face harsh penalties, including imprisonment, torture and other grave human rights violations. The UAE's repressive tactics are not limited to dissidents and activists, but to anyone perceived as a threat to its interests, including international businesspeople operating within the country's borders.

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has recently launched an extensive campaign to silence opposition, marked by a stark disregard for justice and human rights. This crackdown includes a series of arrests, summonses, and deportations targeting individuals who criticize Israel’s actions in Gaza, blatantly violating the right to freedom of speech.

The State Security Apparatus (SSA)

As HRW wrote recently, the SSA is the highest authority on UAE state security matters.

Created on June 10, 1974, the SSA and has played a leading role in the crackdown on peaceful dissent in the country, starting with the mass arrests campaign launched in 2013 against Emirati civil society. That year, SSA agents arrested, secretly detained, and tortured over a hundred lawyers, judges, students, and other intellectual figures who signed a petition asking for democratic reforms. […] Since then, the SSA has continued to perpetrate widespread human rights violations, including enforced disappearance, torture, and arbitrary detention.

The SSA operates in great secrecy under the direct control of the UAE President, on the basis of a law that has never been made public. According to a leaked draft from the Emirates Detainee Advocacy Center, the law, which was amended in 2003, grants the SSA broad and unconstrained powers, allowing the SSA to act without any institutional, judicial, or financial oversight. For example, it can gather and analyze information on “any political activity” and “monitor social phenomena.” The SSA President has the power to place suspects in custody up to three months and make any decision that is binding on all security apparatuses. The SSA is also allowed to establish security offices in any federal ministry, government office, embassy, or consulate abroad.

Recent examples of SSA activities were the crackdown on 44 civil rights defenders in 2023 and the crackdown on Bangladeshi workers protesting against their own government.

As the aforementioned DAWN-Report describes, spying and surveillances by SSA reaches far beyond the borders of UAE:

The United Arab Emirates has demonstrated a blatant disregard for the rule of law and individual rights, engaging in widespread spying and surveillance tactics against critics and dissidents both within and outside its borders. The Emirati regime has been accused of employing sophisticated cyber-surveillance tools to hack into the phones, email accounts and digital communications of activists, journalists and even foreign government officials.