“Our friends were detained on suspicion of being LGBTIQ+, now they are dealing with deportation.” – The double violence of xenophobia and queerphobia in Turkey

August 4th, 2023 - written by: Border Violence Monitoring Network

Border Violence Monitoring Network (BVMN) is an independent network of NGOs, associations and collectives that monitors human rights violations at the borders of Europe and advocates to stop violence against people on the move.

This report from Turkey focuses mainly on the intersections between the struggles faced by the LGBTIQ+ community and the general conditions of detention and deportation in the country. This has come to the fore after severe repression against activities during Pride Month along with surge in police sweeps, detentions and deportations as the AKP governement seeks to show it is cracking down on immigration. In the report, we give a brief overview ofthe current situation, how the detention-deportation tool has become a ready tool against the even the most minor resistance or dissent and sharean analysis from a long-time participant in LGBTIQ+ and feminist struggles in Turkey.

Turkey has been a key outpost of the EU’s ‘migration management’ policy since the signing of the so-called EU-Turkey deal in 2016. Removal centres (GGMs) in the country, rife with documented human rights abuses, have been built and maintained with tens of millions of euros funnelled into them by the EU.

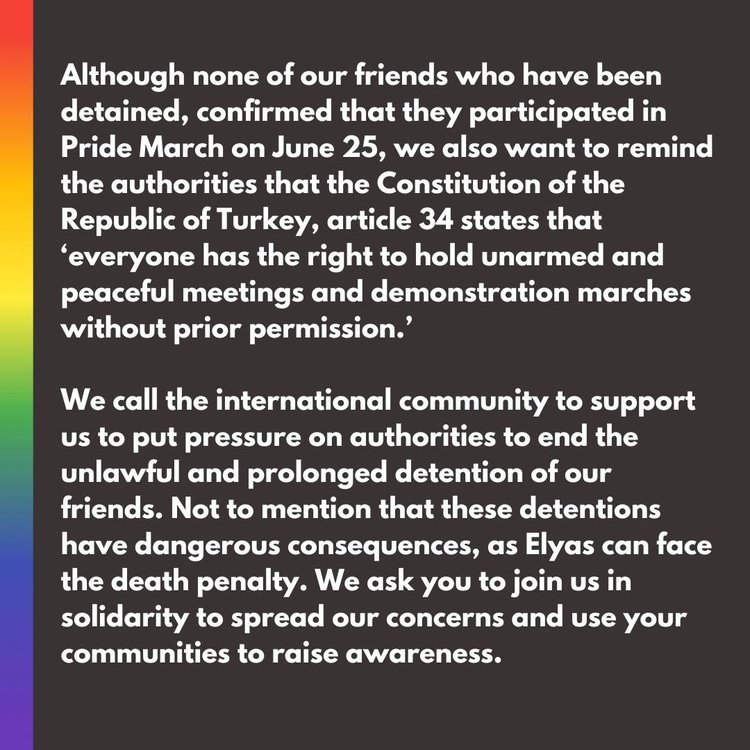

More detailed updates from the cases that are being followed by Istanbul Pride and resources to spread the word in various languages can be found at the #pridecantbedetained page and their Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

#Pridecantbedetained

Istanbul’s Pride March took place on Sunday June 25, the culmination of a month of events in which there were severe crackdowns involving a litany of rights violations against the organisers and participants at events across Turkey such as picnics, talks, or film screenings.

Following the Istanbul Pride parade, police violently intervened, arbitrarily kettling and arresting people en masse in the vicinity of where the paradeand press statements had taken place. A total of 113 people were detained in Istanbul, of which five were non-nationals. At least 52 people were also detained in Izmir on the same day, with similar scenes witnessed since in Adana and Eskişehir.

The five non-nationals detained in Istanbul hold Iranian, Libyan, Russian, Australian and dual Portuguese & South African citizenship respectively and the circumstances of their legal status in Turkey also varies. Following their arrest, many were swiftly served with deportation orders and sent to different EU-funded Removal Centres (GGM) in Turkey. Some were simply detained without any due process, including no access to information on the reasons for their detention or its possible duration. All of those detained have faced forms of physical abuse, denial of medical care and other rights violations, while any degree of accountability in terms of bureaucratic procedures was further stunted with the excuse of the incidents coinciding with Eid and the public holiday period.

The most recent update from the Pride Committee on July 18 states that the Russian, Australian and dual Portuguese-South African friends have recently returned to their countries of citizenship through the “voluntary” repatriation process – a mechanism well known to be voluntary by name only.

Elyas Torabibaeskendari, the Iranian national arrested on June 25, was issued a deportation order despite having international protection status and risks possible execution if deported to Iran. Elyas, along with the Portuguese-South African and Russian friends, was transported with their hands reverse handcuffed for 12 hours from Istanbul to the Urfa Removal Centre. Since then, Elyas has already experienced an assault by another detainee his lawyers believe to be from ISIS. An appeal against the administrative detention decision for Elyas was rejected and so, unless the Provincial Directorate of Migration Management intervenes, Elyas will remain detained in the Removal Centre.

The Libyan detainee was moved from Tuzla to Selimpaşa Removal Centre, in Silivri, Istanbul and has been in need of urgent medical care. They remain at Selimpaşa, while an appeal against the administrative detention was rejected.

The Istanbul Pride Committee and its wider network continue to follow the cases and offer support, while having to balance wanting to inform the public and spread the word on the detained and at the same time weighing up issues of privacy and security. They state, “We (as their friends, lawyers, and activists) try to act cautiously, knowing that any information we share with the public about them and their process may affect both the legal process and our friends' psychological and physical health in the removal centres and afterward.” In the cases of both Elyas and their Libyan friend, the Pride Committee intends to file further appeals this month, when their right to appeal is restored, and will continue to follow their situations closely. As for those who already “voluntarily” returned, they were required to also pay for their own travel expenses, costs that were covered by the Pride Committee, placing another weight on the support work.

Fasttrack deportation

This is not the first time that deportation orders have been used as punishment for foreign nationals accused of association with what are not unlawful demonstrations in Turkey, as has been seen in the wake of many feminist solidarity demonstrations in particular in recent years. In fact, even those who have managed to formally regularise their stay in the country do not need to be accused of participating in demonstrations to end up with a deportation order.

The recent case of one Istanbul resident is indicative, where Sona Y., an Azerbaijani woman with legal residency, has ended up in a Removal Centre following an argument with a neighbour who physically attacked her and verbally abused her with racist and sexist threats. She eventually accepted to be “voluntarily returned” to Azerbaijan due to the psychological pressure she had experienced and was deported on July 22. Her neighbour, the assailant, a man with connections to the ruling party, meanwhile remains free to publicly continue threatening her, indicating that such aggressors are basically deputised in such scenarios. A more severe fate could await Iranian Mona Amerloo, who was unassumingly expecting to renew her Turkish residence permit at her local Directorate of Migration Management office in Bursa and ended up in a Removal Centre with a deportation order based solely on ‘intelligence’ claims that she constituted a threat to national security. She had openly criticised the Iranian regime online during the protests that followed the death in police custody of Mahsa Amini in Tehran last September. Mona is currently being held in Bursa Removal Centre while an appeal against her deportation order is pending.

All of these largely isolated but similar cases have taken place in a period where hatred and violence against migrants and refugees and against LGBTIQ+ communities have become more intense, playing out in the broader context of a deepening economic crisis, the impact of the earthquake that hit Syria and Turkey in February and the abysmal state response to it, and, most recently, the presidential and general elections. Xenophobic, nationalist, homophobic, and patriarchal politics are on the rise and, as elsewhere, they rely on targets to scapegoat while diverting attention from the main structural causes of further immiseration and desperation among the general population.

Over the past year, the Turkish government has ramped up mass detention and deportations, especially of so-called “irregular migrants,” predominantly people from Afghanistan. Concurrently, the prolonged election buildup and overall campaign process paved the way for a more vicious anti-migrant atmosphere in the country, with the main opposition candidate having vowed to “send home” all Syrian refugees in Turkey, bandying grossly exaggerated figures of an alleged 10 million “illegal refugees” living in Turkey.

A recent series of highly publicised operations boast of “illegal immigrants” being detained in the hundreds, and have been carried out in broader sweeps across various cities and city districts on a scale and intensity beyond what has been experienced in recent years. Beyond knocking on private residential homes, entering private workplaces, stopping on street-corners or on public transport, police have resorted to other disproportionate tactics such as waiting outside the Afghan Consulate in Istanbul to stop and pick up anyone without papers. Meanwhile, clips of African people of various nationalities being chased, beaten and detained by uniformed or plain-clothes officers have become more prevalent online. Many African migrant workers now report being in fear of leaving their homes because of the risk of detention, while initiatives have spread across some platforms urging Africans not to go to work on Monday 24 July in protest against the conditions they are now being made to endure.Over the past year, the Turkish government has ramped up mass detention and deportations, especially of so-called “irregular migrants” (predominantly people from Afghanistan). Concurrently, the prolonged election buildup and overall campaign process paved the way for a more vicious anti-migrant atmosphere in the country, with the main opposition candidate vowing to “send home” all Syrian refugees in Turkey, with these promises later extending to grossly exaggerated figures of an alleged 10 million “illegal refugees” living in Turkey. A recent series of highly publicised operations boast of “illegal immigrants” being detained in the hundreds, and have been carried out in broader sweeps across various cities and city districts on a scale and intensity beyond what has been experienced in recent years. Beyond knocking on private residential homes, entering private workplaces, stopping on street-corners or on public transport, police have resorted to other disproportionate tactics such as waiting outside the Afghan Consulate in Istanbul to stop and pick up anyone without papers. Clips of African people of various nationalities being chased, beaten and detained by uniformed or plain-clothes officers have become more prevalent online. Many African migrant workers now report being in fear of leaving their homes because of the risk of detention, while initiatives have spread across some platforms urging Africans not to go to work on Monday 24 July in protest against the conditions they are now being made to endure.

Removal Centres

Meanwhile, Turkey’s Directorate General of Migration Management continues to release glowing statements regarding the impact their operations are having, stating that in June 2023, 15,591 irregular migrants were detained, 6,883 irregular migrants were deported, and 23,450 people were reportedly blocked from “irregular entry” into the country. On 27 July President Erdoğan announced that 36,000 irregular migrants had been detained in the past two months, of which 16,000 were deported.

Turkey has a total of 30 Removal Centres, which are largely EU-funded and developed in tandem with various EU migration management initiatives. They are located all over the country, their conditions and functions vary, but those detained are systematically denied basic rights and the centres are largely inaccessible to lawyers or NGOs. Reports of various types of abuse, denial of medical care, and grossly inadequate nutrition surface frequently, and coerced “voluntary returns” are a staple method of gaining formal consent for deportation. It was recently reported that, amidst such conditions, a group of detained refugees at Çankırı Removal Centre set fire to beds and duvets, resulting in a full evacuation of the centre. Sona Y., mentioned above, had declared on June 5 that she intended to go on hunger strike in the Selimpaşa Removal Centre if conditions – poor hygiene, denial of medicine, beatings – did not improve and she was not released. The detention-deportation tool of state punishment has become more of an everyday risk and there is an urgent need for solidarity groups to build awareness of the conditions in Turkey’s removal centress and to spread the struggle against them. Thankfully steps are being taken in this direction, as with the recently formed campaign group ‘GGM’lerde Neler Oluyor’ (What is Happening in the Removal Centres?), who state: “The political power wants to turn anti-immigrant, anti-women, and anti-LGBTI+ hostility into routine practices [...] In the current situation, as a result of anti-migrant policies, arbitrariness and lack of regulation, Removal Centres have turned into torture chambers.”

Solidarity remains

To get a more direct account of much of these issues, we spoke with Saida, who is involved in the LGBTIQ+ and feminist movements in Turkey and also has first-hand experience of many of the dire conditions discussed above.

Could you briefly share who you are and what group or organisation you’re involved in?

My name is Saida. I have been living in Turkey for more than 10 years. I am an immigrant. Rather than any specific associations, I am organised in the Pride Committees that meet on a voluntary basis every year. Apart from that, I am a member of a feminist organisation. That said, it also depends on the city I live in. I changed several cities during my time in Turkey due to the fear of security caused by internalised homophobia. However, this year, I could not attend all the meetings of any committee, because I had an ongoing court case.

Do you have any updates on the situations of the five non-nationals detained on June 25?

As the Istanbul Pride Parade Committee, we regularly share updates about our friends. For now, things haven't changed since the last update of July 18 - some are no longer in detention and no longer in Turkey, while the others are still trying to deal with the deportation issue. Our friends were detained by the police after the Pride parade while they were walking on the street, on the assumption that they were LGBTIQ+. In short, the presumption of innocence does not apply to LGBTIQ+s.

What is the background context of these arrests and the repression of Pride and LGBTIQ+ events in general?

Police attacks on Pride parades have been a tradition for years. If I were to share my own experiences, not in general, in 2019, during the Izmir Pride Week, when the week was about to begin, all our events were banned, and at the same time, the police went to the venues where we were going to organise the event and threatened the owners. Despite this, of course, we still did our activities, but our security concerns were very high. It was mainly about the people attending the events. Afterwards, a police attack on the parade was made on the assumption that it was purely appearance-oriented – as we saw in Istanbul this year – and students sitting on the seaside were detained because of their hair colour.

However, the severity of the attack increases every year. While the number of people injured by the police last year was very high in Ankara, the Pride Parade attacks in Izmir this year were quite horrific. More recently still, we can add the attacks on Eskişehir Pride parade to this list. To make matters more complicated, we are also then prevented from reaching legal support because our lawyers can also be detained, as happened recently.

Are there other cases of people being detained and given deportation orders because they are accused of participating in demonstrations or gatherings, or for other types of dissent?

I think it would be better if I explained this question through my own experience. I was detained on the grounds of participating in the demonstration on 25 November, the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, held last year, and sent to the Removal Center. By the way, I would like to state that participating in the demonstration is not prohibited even according to Turkish laws and cannot be a reason for deportation. However, without any investigation against us, the Immigration Administration made an outrageous decision on the charge of "threat to public security". Thanks to the insistence and persistence of feminist and LGBTIQ+ organisations, we left the Removal Center, witnessing a great solidarity, and we won our appeal against the deportation decision. Because we did not commit a crime according to the law, we were punished as a completely arbitrary practice without any legal basis, just because we do not think or behave the same as them.

I would like to say one or two things about inhuman treatment in Removal Centers. When I was there, I remember answering the officer's question of "how are you?" saying, "I am exactly as I could be expected to be when I’m in a prison and in a mental health hospital at the same time." Because of intimidation and harassment, naked searches, psychological and physical violence, etc., they are trying to ensure that people's mental balance is deteriorated and they voluntarily demand deportation. Personally, I prefer to say that I stayed in one of those horrible prisons you see in the TV series, rather than in a Removal Centre.

What kind of groups have been involved in the support work since the Pride arrests?

The reality is that everyone who does not think like the government in this country is punished, generally in the same way. The police, who beat us two years ago in the Istanbul March 8 protest, attacked and beat the doctors who were protesting a few days later. If you are the one seeking your rights tomorrow, you will be subjected to the same violence that we have been subjected to. But let's say that a group that’s pro-government is doing the protest, and for example, they gather to attack our picnic event or whatever it may be. Still, we’re the ones that will end up facing a beating from the police.

After the attacks this year, LGBTIQ+ and feminist associations took part in our work, as they do every year. However, especially after what was done to our foreign national friends, groupworking with migrants also offered to act together, and now we continue our struggle in great solidarity.

What do you see as the specific challenges of creating solidarity across different social groups or movements in these conditions?

Even organising around a single issue in a country like Turkey is difficult anyway. Over and above some problems like differences between groups or just geographical distance, I think, the basic fact that the political agenda in Turkey changes so quickly is what makes building broad solidarity alliances difficult.

Because of the volatile political climate and struggles, the focus of mixed solidarity efforts can then be quickly dispersed. So the challenge of building alliances across broader social groups reallycomes down to that. Apart from that though, and even if it is difficult to organise and coordinate simultaneously in different parts of the country, I would say solidarity remains alive, and we can still manage somehow to find a common denominator.

What role do you see for international solidarity in this specific case and in general?

We are all people who are marginalised because of predetermined boundaries. We can demand solidarity from the international LGBTIQ+ community, because our otherness is always the same. It would be good for us to hear our voices, which they try to silence here, and our press statements loudly all over the world. Or if we join our demonstrations together, there are not enough prisons from all over the world to fit all of us :) I think it is necessary for the entire international community to know that Removal Centers have been turned into torture centers that the UN and Europe have paid for.