Morocco

Published June 10th, 2025 - written by: migration-control.info

Introduction

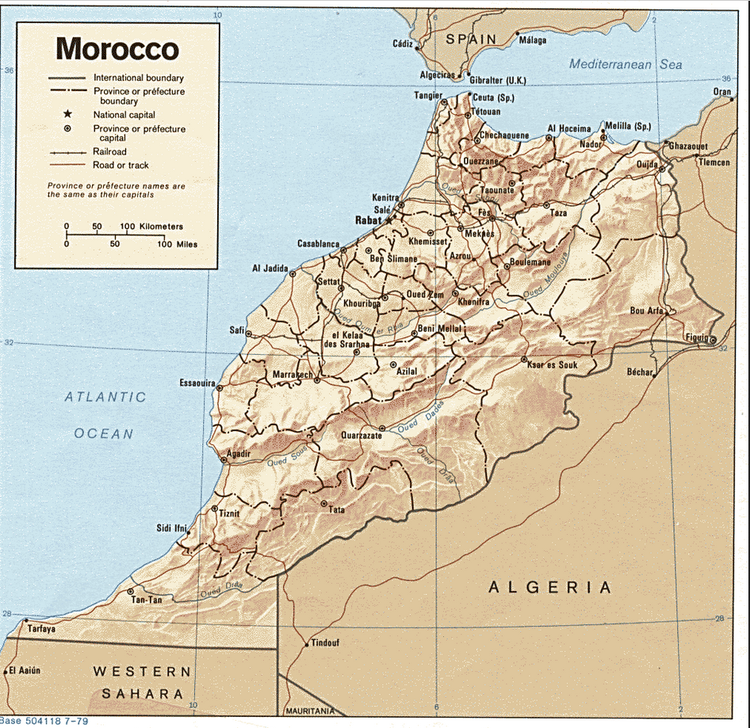

Morocco, a country with a rich history and diverse cultures, today faces numerous challenges that deeply affect its economy, social structure and political landscape. Due to its geographical location on the border of two continents, as well as its two coastal borders to the Mediterranean and Atlantic, Morocco plays an important role in the European Union’s (EU) externalisation policy, particularly through its control of the Strait of Gibraltar and the Spanish exclaves of Ceuta and Melilla.

Morocco has maintained close relations with Europe for decades, in which the issue of „regulating migration flows“ is a precarious centrepiece. The precariousness lies primarily in the practices that violate human rights, which are committed in complicity between Morocco and the EU. Due to its geographical location, Morocco plays a key role in migratory movements on the African continent and between Europe and Africa. The country is an important point of departure and transit for people from various African countries wishing to cross the sea to Europe. This has led to a policy of ever-increasing border surveillance and control in cooperation with the EU. At the same time, Morocco is trying to profit from this situation as much as possible.

Morocco became independent in 1956. However, there are still considerable social and economic problems and political grievances, many of which can be traced back to the period of colonisation.[1] These problems are exacerbated by the regime's undemocratic practices and political repression. The Moroccan monarchy (Makhzen) rules the country almost unchecked, while local democratic forces and human rights organisations (including those active in the field of migration policy) continue to face significant challenges.

(C) Map utexas.edu

1. Economy, Social Structure ,Emigration

1.1 Geography

Morocco covers an area of 446,550 km². If you add the territory of Western Sahara, which was largely annexed by Morocco in 1975 after the withdrawal of Spain,[2] the total area is 712,550 km². Around 38 million people lived in Morocco in 2024 (excluding the 600,000 inhabitants of Western Sahara). Two thirds of the population live in the north-west and west of the country; around 60 % of the population live in cities. More than two thids of the population are Amazigh, the majority of whom have been Arabised.

The country is separated from the European continent by the Strait of Gibraltar. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west. The borders with the Spanish exclaves of Ceuta and Melilla on the Mediterranean have a total length of around 16 kilometres. This section of the EU's external border is characterised by a massive social divide: The per capita income north of the border is ten times higher than on the southern side.

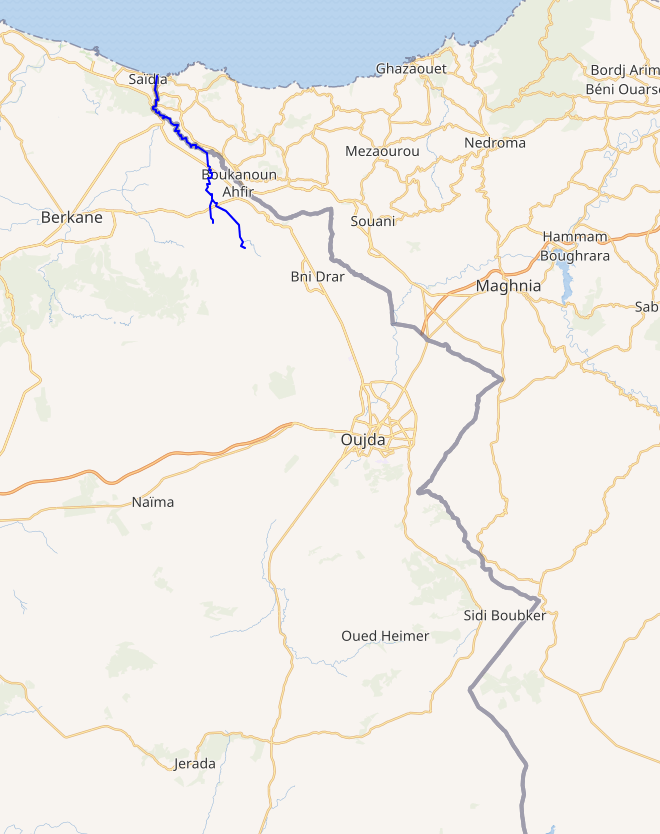

In the east, Morocco shares a border with Algeria which is around 1400 kilometres long. The border crossings have been formally closed since 1994. The border line is secured on the Moroccan side with trenches and embankments and on the Algerian side in sections with an electronically monitored border fence. Numerous smuggling and transit routes lead across this border. Since the beginning of 2022, the border has been even more heavily secured as a military security zone. The prices for smuggling across the border at Oujda, which is used by most migrants who want to try their luck in Algeria, Tunisia or Libya, have multiplied.

To this day, the mass expulsions of Moroccans from western Algeria and Algerians from eastern Morocco, which took place in the first three decades after independence, are instrumentalized by the governments for the purposes of mutual blame and hostilities. The border closure is also justified by the conflict over Western Sahara and, since the 1990s, by the fight against cross-border jihadist terrorism.

The southern border with Western Sahara, 80% of which is annexed, stretches over 443 kilometres. Western Sahara, which is occupied by Morocco, is fortified with numerous military checkpoints. From north to south, Morocco has built a 2,400 km long, mined sand wall along Western Sahara. UN blue helmets are stationed along this wall as observers (MINURSO).

The border between occupied Western Sahara and Mauritania is passable through a heavily guarded checkpoint. A new border crossing has been announced by Mauritania and Morocco. The planned road is apparently nearing completion. The implementation of this project by both states is likely to lead to tensions between the neighbouring state of Mauritania and the Polisario, which is a military and political organisation striving for the independence of Western Sahara.

Further information on the nature of border areas can be found in chapter 4.1.

1.2 Economy and Socio-economic Aspects

In Morocco, the development gap between the economically up-and-coming regions such as Tangier, Rabat, Casablanca, El Jadida and Marrakesh and the rural, remote areas such as the Anti-Atlas Mountains or the Reef region is widening. Although absolute poverty (according to UN criteria) fell between 2001 and 2014, the differences between urban and rural areas and the income gap between those at the top and those at the bottom remain. The years 2014 - 2019 saw slight increases in income for the poor, but these fell back to 2014 levels during the Covid period. The growth of the formal economy has hardly changed the share of low-paid, informal employment. Half of Moroccans are self-employed and only a third of workers have a job with an employment contract. A tax-financed pension system has been in place since 2012, but pensions are very low. The impressions from the "Land of Contrasts" that Quantara published in 2014 are still relevant.

Poverty sometimes appears idyllic to tourists. (C) T.S.

Rural Poverty

In some rural regions, particularly in the Gharb plain, large estates and farms characterise the landscape and there is a certain standard of living. However, these regions stand in stark contrast to the overwhelming poverty and structural weakness in the majority of rural Morocco. This structural poverty, which is reflected in the inadequate development of important access routes and roads, for example, had a fatal impact on the victims of the 2023 earthquake, as it made it difficult for recovery and rescue vehicles to access the affected areas.

Morocco's peripheries include the Rif Mountains and Western Sahara in particular, but also the Atlas region, where the major earthquake occurred in 2023. These regions are severely disadvantaged politically, socially and economically by the central government and are characterised by widespread poverty, chronic unemployment and a lack of basic services and infrastructure. These problems are exacerbated by the continued suppression of political rights and the disregard for different cultural identities.

The expansion of education over the last 20 years has produced an educated young generation. However, unemployment among young people with a university degree is high. Official unemployment has risen in recent years, reaching 30% in some regions. In any case, only 15% of students graduate from high school. The majority of non-graduates work in the informal sector - in agriculture and the service sector - and have no opportunities for advancement and no social security. Two thirds of all jobs in Morocco and almost all jobs in agriculture are informal. A good 40% of the Moroccan population is dependent on agriculture, which accounts for 17% of GDP. Semi-feudal social structures and corruption are widespread. The cultivation and export of cannabis was partially legalised in 2021, and around 1 million people are economically dependent on it.

The Rif Mountains form a microcosm of structural inequality in Morocco. For decades, the local communities in these regions have been struggling with a lack of educational opportunities, inadequate healthcare and high unemployment. The once dominant small-scale agriculture with subsistence farming has lost its importance, apart from the cultivation of hashish.

The Sahrawis in Western Sahara, a disputed region with an unresolved political status for decades, fare even worse than the population in the Rif region. Most of Western Sahara has been under Moroccan control since the withdrawal of the Spanish colonial power in 1975. There are only 105,000 original inhabitants and 180,000 military personnel. Many families in the heartland of Morocco have relatives who have relocated to Western Sahara due to pay and bonuses. The protracted conflict over independence and self-determination[3] has led to a persistent social divide in this resource-rich but socially disadvantaged region.

While the colonisation of Western Sahara and, above all, the relocaton of the military from the heartland has stabilised the royal centre of power, the ongoing marginalisation and oppression of the peripheral areas not only contributes to the exacerbation of social and economic inequalities within Morocco, but also threatens the stability of the country as a whole. The dissatisfaction and frustrations of the local population regularly lead to social unrest and uprisings. The royal regime's active neglect of the political rights of these regions remains a fundamental obstacle to the democratisation of the country. It is questionable whether the earthquake aid announced by the Makhzen will change this.

Urban Development

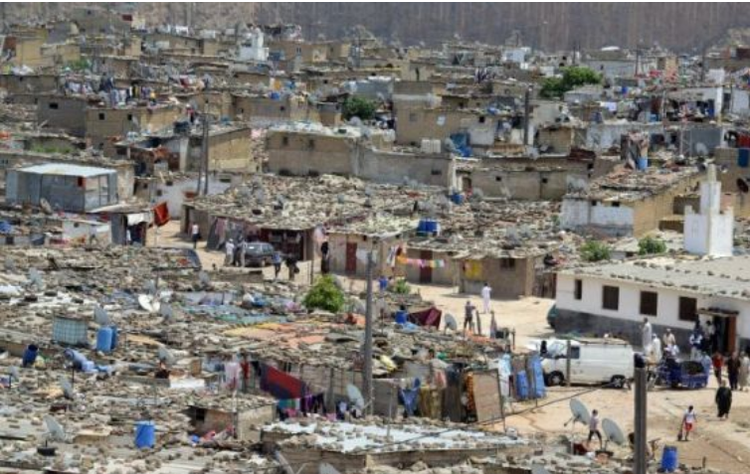

In urban centres, wealthy and socially disadvantaged population groups clash starkly. The rental market is not regulated. Flats are often overcrowded because many younger people without an income sleep in their parents' homes. Similarly, black migrants often live several to a room. The Bidonvilles (French term for „slum“) have repeatedly been the starting point for protests, but also for jihadist attacks (Casablanca 2003). There have been repeated plans to demolish the bidonvilles since 1981; a new five-year programme "Cities without slums" was launched in 2024. However, these programmes not only demolish affordable housing, which also serves as accommodation for many migrants, but also attack the neighbourhood lifestyle of the urban lower classes. This year, 2025, there were protests against the demolition in Rabat and Casablanca of old neighbourhoods, with the king, who likes to present himself as the king of the poor, being held personally responsible.

Economic Development

Important traditional economic sectors are the export of phosphate, agricultural products and fish, whereby the royal family has great influence over the main companies in these sectors (e.g. royal monopoly of the Office Chérifien des Phosphates). The king is one of the richest men in Africa.

The Moroccan economy consists predominantly of small companies: 97.3% of businesses employ fewer than ten people and contribute 54.2% to total employment. However, over the last 10 years, modern industrial development has begun in some centres beyond the traditional industrial location of Casablanca (or Aïn Sebaâ). In the prosperous Tangier region, the port of Tangier Med was opened in 2007, and extensive industrial facilities have been built in its vicinity, including the largest automobile factory in Africa, Renault TangerMed. More than 200 Chinese companies are to be established in the "Tangier Tech City". South of Casablanca, near the deep-sea port of El Jadida, is the region of phosphate mining and the fertiliser industry. An industry for basic materials for battery production and a "gigafactory" for batteries are currently being built here. The growing number of call centres for the French-speaking region should also be mentioned. Major projects such as the expansion of a railway network for high-speed trains or the "Tangier Med" port facilities are being financed with loans, mainly from France and the Gulf States. However, the Chinese Road and Belt Initiative has also led to billions being invested. China is trying to capitalise on the fact that Morocco has negotiated privileged trade agreements with both the EU and the USA.

However, all these lighthouse projects have little impact on the "ordinary people" in the poor neighbourhoods of the cities or even in the countryside.

1.3 Morocco as a Country of Emigration

Three to four million Moroccans live in emigration. That is up to 12 per cent of the total population.[4] 84% of these emigrants live in the EU. Since the 1990s, Morocco - ahead of Turkey - has accounted for the largest number of immigrants in the EU, with a strong upward trend compared to Algerian and Tunisian emigration.

In the 1960s and early 1970s, there were official bilateral labour recruitment agreements between Morocco and several Western European countries. After the recruitment stop in 1973, the bottleneck of family reunification, marriage or a life in Europe without papers under the constant threat of deportation remained the only choice for most. This was only possible in cities with large migrant communities.

In 1992, under pressure from the EU, Spain introduced visa requirements for Moroccans, forcing people to cross clandestinely on small boats. In the summer of that year, around 30,000 people crossed the Strait of Gibraltar, which subsequently became the largest mass grave in post-war Europe. Migrant and human rights organisations in Spain brought the mass deaths off Gibraltar to public attention: between 1991 and 1996, between 2,000 and 4,000 people probably died in the Strait of Gibraltar alone.[5]

Moroccans in the EU require a visa, but Europeans in Morocco do not. Many pensioners from France and Spain spend their retirement in the Moroccan sun. Spain issues visas for Moroccan seasonal workers, exclusively for married women. Travelling and staying in the MENA region has become much more difficult, if not impossible, for Moroccans aged between 18 and 40 in recent years, especially for unaccompanied women. However, the desire to emigrate remains high:

The three countries Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia have one thing in common: people, especially young people, just want to get away.

In many families, transnational networks have developed to facilitate migration, such as trading labour contracts, joint investment in the travel expenses of an "economic martyr" or family reunification through marriage to a person already living in Europe.[6] The state has encouraged emigration from the outset, particularly because remittances represent a significant proportion of the income for the poor population. Remittances currently amount to around 10 billion euros annually. These remittances are one of Morocco's most important sources of foreign currency and are more significant than income from tourism and foreign direct investment.

2. Monarchy, Religion and Social Control

The Moroccan monarchy has been led by King Mohammed VI since 1999 and forms the centre of the country's political power structures. After the Arab Revolution in 2011, there were some reforms, but the monarchy continues to be the key player exercising political, economic and religious authority. Sunni Islam is the state religion and gives the royal house majesty and legitimacy: the king is the supreme state and religious authority in one person. The Alawid dynasty has ruled for centuries and derives its rule directly from a kinship with the Prophet.

This close intertwining of monarchy and religion often leads to the suppression of alternative political or social discourse. Religion is used as an instrument to suppress dissent and consolidate existing power structures. Under the shield of stability and cohesion, the regime has developed a sophisticated strategy of social control and surveillance that draws heavily on religious institutions and traditions.

Political arrests and convictions are often not made on the basis of political content, but with the help of morality-police-constructs that are accompanied by corresponding smear campaigns in the mass media. Urban and rural areas are monitored by the police with the help of neighbourhood social control. The informal moral police thwart multiculturalism in everyday life, as well as the formal valorisation of women's rights and gender-related and religious freedoms.

In addition to this micro-control, there is also extensive electronic and digital surveillance of activities and freedom of expression on social media. Critical comments on Facebook or political content on YouTube can lead to the arrest and conviction of unpopular journalists or rappers.

The political elites in Morocco are characterised by loyalty and allegiance to the throne. Within the apparatus of power, they form a powerful alliance for the defence of the kingdom's political hegemony; this results in mutual protection, consideration of political interests and access to economic privileges. The network of elites is constantly changed and renewed by the king in order to keep them under control. New figures, some from peripheral regions, are integrated into the network and old ones are replaced, be it through coercion, bribery or by the granting of political privileges. According to the 2011 constitution, the king is the most important member of the executive power. Although the 2011 constitutional reform has strengthened the position of the prime minister, it does not set any clearly defined limits on the Makhzem's regime. Neither the person of the king nor the institution of the throne may be directly and publicly questioned or criticised. All of the king's demands must be met unconditionally. However, there are rumours that the king is ill, which could call the current power structure into question

As part of the annexation of Western Sahara in 1975, the Makhzen was able to relocate the military as a competing power factor from the core state to the subsidised Western Saharan south - two military coup attempts had previously taken place in 1971 and 1972. This eliminated the military as a power factor. Between 2003 and 2014, military spending was increased considerably without any recognisable political ambitions on the part of the military.

3. Protest Movements and Repression

People have been taking to the streets in the Rif and the rest of Morocco for years. They have been demanding an end to humiliation, "hogra", by the police and state officials, as well as investment in public services and job creation. It was no different in Tunisia in 2011, but in Morocco the so-called "Arab Spring" did not have the same intensity as there or in Syria, Egypt or Libya. Nevertheless, it is inaccurate to speak of a "Moroccan special case". In fact, the protests since 2011 have been concise and omnipresent in Morocco too. They showed a clear will for political change, driven mainly by the Moroccan youth and urban population. These movements exposed the outdated, inefficient and reactionary structures of the country's political leadership and marked a turning point in the political public sphere by questioning the monarchy itself for the first time - an issue that was previously considered untouchable. Although the motivations for popular protests during the Arab Spring were similar in the respective countries, the movement in Morocco did not seek a radical overthrow of the regime, but demanded state reforms with regard to the constitution, the labour market, education and poverty, as well as against the marginalisation of young people.

The 20 February Movement

The "20 February 2011" movement and the protests in the Rif region in 2017 against social injustice and political oppression illustrate the ongoing resistance of parts of Moroccan society against the regime. Its response has always been characterised by repression and far-reaching restrictions on freedom of expression and assembly. Peaceful activists, journalists and political opponents were intimidated, arrested and sometimes even tortured. The Makhzen's repressive treatment of protesters has become increasingly severe in the public sphere, further fuelling discontent among the Moroccan population. The actual socio-economic concerns of the protesters and the profound problems in the country's political leadership were largely ignored in the official discourse. The reforms were merely a tactical response by the Makhzen to sway public opinion in favour of the regime. In fact, they contributed to calming the situation and weakening the protests, while in other Arab nations they escalated.

Night-time demonstration in Casablanca in 2011: Supporters of the "20th February Movement" demonstrate for the release of Mouad Belghouat alias el-Haket (the outraged), a rapper who was imprisoned and very popular among young people. (C) T.S.

In the course of the protest movement, some demands were adapted: Originally, the protesters demanded reforms to establish a "parliamentary monarchy" in Morocco. However, internal differences within the movement led to this demand being modified to demand a "democratic constitution" that would reflect the will of the people. The government acted quickly and skilfully to avoid a radicalisation of the demands or an escalation of the protests by introducing formal constitutional reforms and an apparent separation of powers between the prime minister and the king. The activities of the human rights and democracy movements were pushed out of the public sphere and legally restricted.

This political strategy is having an impact on both the protest movements and the government. The government sometimes made symbolic concessions or implemented minor reforms in response to the demands. Protest movements often accepted the proposed reforms in order to legitimise themselves to the state, suggest constructive cooperation and be able to continue their activities. This interplay explains the end of the 20 February Movement protests in Morocco in 2011. Although the protest movement represented a significant challenge to the royal regime and was able to persuade it to reform the constitution, it was unable to initiate long-term political and social change: Political debates and decision-making processes were not democratised and continue to take place in the exclusive bodies of the country's political elites and to the exclusion of the social majority.

Protests in the Rif Region

In autumn 2016, waves of protest flared up in the Rif region in north-western Morocco. These were triggered by the tragic death of fish vendor Mohsen Fikri, who was crushed to death in a rubbish truck while trying to reclaim his goods confiscated by the police. In the months that followed, the protest movement spread to other parts of the country. The protesters' concerns were mainly about creating jobs and improving the region's infrastructure, without directly challenging the regime. The protests continued for months and gained momentum, not least as a reaction to the increasing repression. After years of silence, the entire population of the region was directly or indirectly involved in the demonstrations. Women played a leading role in these protests. The conflict escalated when the government arrested one of the leaders of the movement, Nasser Zafzafi, along with others.

This was followed by a series of court cases. In 2018, more than 100 activists were sentenced to prison. Some of those convicted were later pardoned by the king, while Zafzafi and other leaders are still serving their sentences. The regime continues to spread the misleading propaganda via the media and mosques that the movement is "separatist" and therefore "dangerous" - a lie that can also be heard in the European diaspora. Nasser Zafzafi has never called for the independence of the Rif region.

The ongoing protests by the Amazigh population in the Rif region mark an important point of political and social discontent. Despite the parallels between the underlying grievances, such as unemployment and corruption in state institutions, which triggered both the Rif protests and the 20 February movement, there are clear differences in the structure and methods of the two movements, especially with regard to the regional anchoring of the protests in the Rif.

Protests in Zagora and Jerada

One year after the Rif protests, these protests were continued in other peripheral small towns inhabited mainly by Amazigh populations. At the "Mainifestations de la soif" in the oasis town of Zagora, on the other side of the Atlas Mountains in the south, the population demonstrated against the non-functioning public water supply in September 2017. Another demonstration on 8 October was violently dispersed. A few days later, the king set up a commission to solve the water supply problem.

The protests in Jerada, a town of 40,000 inhabitants, began on 22 December 2017 following the accidental death of two workers in one of the local coal mines. In this small town, a good 50 kilometres southwest of Oujda, there had been a coal mine since colonial times, which was closed in 1998. After the closure, there were repeated protests and informal coal mining in self-built shafts. On 13 March 2018, the government issued a warning that it had the power to ban "illegal demonstrations in public spaces". In an incident on 14 March, captured in a video that went viral on social media, police vehicles drove quickly into a group of protesters, with one of them hitting and seriously injuring a 16-year-old boy. From that day onwards, police officers in Jerrada broke into homes without showing warrants, beat several men during arrests and smashed doors and windows, activists told Human Rights Watch.

4. Border Geographies and Migration Routes

We have already outlined the geography of borders in section 1.1. Here we describe entry into Morocco (4.1) and the struggles over migration routes (4.2). Entry to Morocco is not a problem for people from the EU, as all nationals of EU member states receive visas directly upon entering Morocco. Nationals from many African countries are subject to a visa requirement, which makes it considerably more difficult for them to enter Morocco on a regular basis. However, if migrants and refugees want to continue their journey from there to Europe, leaving the country proves to be a far greater challenge. In recent years, the Moroccan state has developed practices that allow it to profit from sub-Saharan migrants as a bargaining chip, especially vis-à-vis the EU. This profit stands and falls with the possibility or prevention of onward travel. As far as the disregard for human rights is concerned, the "migration partnership" between Morocco and the EU has become complicit.

4.1 Entry into the Moroccan Territory

The forms and (border) points of entry to Morocco as well as the associated obstacles and human rights violations are largely determined by the social and geographical origin of the migrants. Citizens of Cameroon, Nigeria or Togo, for example, need a visa to enter Morocco. Many people are denied this access, meaning that they are dependent on overland routes to Morocco, which lead through the Sahara and across the Algerian-Moroccan border.

However, verification and regulation mechanisms are now also being applied to nationals of African countries that have signed visa agreements with Morocco. Morocco introduced the "Autorisation électronique de voyage" in 2017, initially for Guinea Konakry, Congo Brazzaville and Mali. Nationals of these three countries are subject to a de facto check, which is equivalent to a visa application. Official entry is often refused.

4.1.1 The International Airport in Casablanca as the Central Border for Entry from Africa

For people travelling to Morocco by plane, Casablanca International Airport is an important hub. While there are numerous direct connections from European airports to various Moroccan cities, African flights always land in Casablanca. The airport plays a key role in the control of arrivals from other African countries. People who are refused entry are sometimes held for days or weeks in the international part of the airport, the "zone d'attente", in accordance with Law 02-03 and are threatened with deportation to their countries of origin. The law provides for access to asylum procedures for those seeking protection, but applications are denied in the vast majority of cases, which constitutes a breach of the principle of non-refoulement. In addition, African nationals are often detained at Casablanca airport when they transit through Morocco to the EU under the pretext of forged documents - a document check outsourced by the EU through Carrier Sanctions, which is usually carried out by employees of the Moroccan Royal Air Maroc. In 2017, the human rights organisation GADEM achieved a success in this context by publicising the forcible detention of a woman from the Central African Republic and her newborn at the airport by the state security authorities and the risk of her unlawful deportation. The campaign succeeded in ensuring that the people concerned were able to travel to Morocco. There are no official statistics on the number of people detained and deported in this way. It can be assumed that many people are deported behind closed doors and without the knowledge of a critical civil society and specialised public.

4.1.2 Border Areas with Algeria and Mauritania

As formal entry into Morocco from other African countries is extremely difficult for many people, they have to rely on informal routes. This form of entry usually leads through Algeria.

Course of the border in the Oujda region

The border with Algeria, which is over 1500 kilometres long, has been formally closed since 1994 and is partially secured by a deep moat. Numerous smuggling and transit routes keep the small border traffic going. African third-country nationals use this porous border situation to travel in and out of Morocco from Algeria. The conditions of this border crossing harbour a great risk. Migrants are brought from one side of the border to the other by so-called "guides". There have been repeated reports of people on the move being cheated and robbed. The first stop on Moroccan soil, the city of Oujda, is known among migrants for cases of deprivation of liberty and exploitation, often supported by police presence or complicity. Since the beginning of 2022, the border has been even more heavily secured as a military security zone and the prices for smuggling people to Oujda have multiplied. The migration of the Moroccan population to Algeria is also affected by increasing criminalisation. The number of border crossings, particularly around the towns of Oujda on the Moroccan side and Maghnia on the Algerian side, has decreased significantly in recent times.

The south of Morocco is a desert region that is difficult to access and Western Sahara is under military control. A 2400 km long sand wall with military bases and observation towers stretches from the south of Morocco to the border with Mauritania. The conditions for entering the country via the southern route are therefore particularly challenging. A new border crossing between the Moroccan-occupied territory of Western Sahara and Mauritania near the town of Es-Smara is due to open in the course of 2025. However, this technically highly equipped border crossing is only likely to be relevant for people with an entry permit. Crossing the border in the militarised desert region outside the border posts involves very high risks due to minefields and is therefore a little-used migration route.

Aerial view of the border fortifications in Western Sahara. (C) Wikipedia

4 .2 The Routes to the North: Migration Movements and Repression

4 .2.1 Routes Across the Mediterranean

After Spain introduced the visa requirement for Moroccans under pressure from the newly founded EU in 1992, the route across the strait at Gibraltar was an important escape and migration route across the Mediterranean for decades. Boat people crossed from the beaches on the Atlantic side of the city, such as Achakkar, or on the Mediterranean side at Tangier Med to reach Spain. Today, Tangier Med is one of the largest and heavily monitored seaports on the continent.

The repression of mobility in the north of the country was systematised from the second half of the 2010s. The extent of the violence is clear from the MSF reports at that time. The violence culminated in the Melilla massacre in 2022. The fight against human trafficking is instrumentalised primarily to prevent migration movements and not to protect those affected - on the contrary: forced removals within the country's borders and refoulement or unlawful deportations still affect people at risk of and affected by human trafficking today. The Moroccan navy intercepts boats in the western Mediterranean and on the Atlantic route and pulls them back to Morocco. In addition, there have been constant raids and abductions inland, particularly in the cities of Tangier, Tetouan and Nador as well as in the forest areas of Belyounech and Gourougou, which have focussed exclusively on Black people. These raids led to mass human rights violations and deaths. De facto deportation centres were set up in areas controlled by the Ministry of the Interior and people were deported without any access to procedural rights.

The security forces' brutal behaviour continues to this day. ASGI and SOLROUTES published a report in April 2025 that states:

Field research conducted between October and November 2024 documents a system of arbitrary detentions and internal deportations that systematically affects those attempting to cross borders into Europe, particularly sub-Saharan migrants, who are also detained in city centres. These practices also affect people under the protection of the UNHCR, minors and vulnerable people, and follow a deeply racist logic of control and repression.

Civil society initiatives are affected by repression in various ways in this ongoing context. Political engagement by Black migrants is only possible under difficult conditions: numerous protests are broken up by force. But European activists are also experiencing massive intimidation and even persecution by the state. For example, the Spaniard Helena Maleno Garzón was deported from Tangier, her hometown, to Spain in 2021 and was banned from entering the country, a ban that is still in place today.

4 .2.2 Border Areas Around the Spanish Exclaves of Ceuta and Melilla

Similar to Tangier, Nador is also characterised by a repressive atmosphere towards illegalised black migrants. Here too, regular raids are carried out in residential neighbourhoods, often under the pretext of arresting smuggling gangs and targeting people smuggling networks. These networks exist - especially due to the problems of crossing the border to and from Algeria. Self-organised networks hardly function any more due to the repression.

The borders to the Spanish exclaves of Ceuta and Melilla are now fortified in extremis. The massacre in Melilla on 24 June 2022, committed by Moroccan security forces under the watchful eyes of the Spanish border police, was a beacon of cooperation between the Moroccan and European authorities.

The border areas around the exclaves are remote: Near Melilla lies the forest of Mont Gourougou and around the exclave of Ceuta the forest of Belyounech stretches across a mountainous landscape that culminates in Jebel Moussa. The remoteness and militarisation of the border areas in the case of Ceuta and Melilla, but also in the area surrounding Tangier, mean that the brutal actions of the security forces can only be documented incompletely. Many migrants who had to flee from security forces in the wooded and mountainous landscape suffered severe injuries. Access to justice in the sense of criminal prosecution of security forces is virtually impossible for people on the move.

As in other parts of the country, the presence of migrants in northern Morocco has been contested time and again since the 2000s. In 2018, for example, the anti-racist group GADEM reported on police operations in northern Morocco in which more than 6,500 people were arrested and in some cases deported to the desert. Similar actions had already been documented by GADEM in 2015. Another important civil society organisation, Association Marocaine de Droits Humains (AMDH), Nador section, reported on further raids in December 2021. The self-organised communities in the camps, which served to secure daily life or organise boat passages and arrangements for crossing the border facilities, were largely destroyed after the massacre in Melilla in 2022.

The unofficial Arekmane detention and deportation centre, located a few kilometres east of the city of Nador, is a showcase for the procedures of the local security forces and the chain deportations to Algeria. This is where people on the move spend the uncertain period between arrest and deportation. In Nador and the surrounding areas, the aforementioned activist group AMDH in particular is present to document and denounce the human rights violations taking place here.

Since the end of the 2010s, there have been numerous attempts to reach the enclaves by water. In this context, people regularly go missing. In many cases, the intervention of the security forces plays a decisive role in the deaths of migrants, such as during the Tarajal massacre in 2014. In 2019, a particularly shocking case for the Moroccan public occurred when the Moroccan navy shot and killed a young Moroccan woman from Tetouan while she was trying to reach Ceuta by boat.

In 2021, in the context of a diplomatic crisis between Morocco and Spain over the Western Sahara issue, there was a massive crossing of the border into Ceuta. Eight thousand mainly Moroccan youths, who were not stopped by the Moroccan security forces, entered Ceuta with swimming rings and bathing boats. They were arrested by the Spanish military; 5,600 were sent back to Morocco the same day they arrived. This push-back was deemed illegal by the Spanish Supreme Court in early 2024 due to the deportees being minors.

Spain recognised Morocco's claim to Western Sahara in April 2022. Since then, the Moroccan security forces have also closely controlled the border area off Ceuta. The brutal actions of the Moroccan and Spanish security forces culminated in the Melilla massacre on 24 June 2022. At least 37 Black people died trying to reach the enclave of Melilla as a result of the brutal intervention by Moroccan and Spanish security forces. To date, there has been no comprehensive investigation into the case and 77 people are still missing. Morocco fenced off the area around Melilla after this incident. In addition, shops and hotels in Nador were banned from selling goods to black Africans or harbouring them.

Recently, it has mainly been Moroccans who have tried to reach the enclaves. In February 2024, some people swam to Ceuta after the Moroccan authorities destroyed their homes in Belyounech as part of a development project. In August 2024, thousands of people attempted to reach Ceuta again, sometimes in thick fog across the water. These people were also deported back to Morocco.

4.2.3 The Atlantic Route

Since 2018, the Atlantic route between the occupied territories in southern Morocco and the Spanish Canary Islands has gained in importance. This is directly related to the extensive closure of the Western Mediterranean route and the routes to the Spanish exclaves. The boats depart from various locations along a coastal stretch of around 800 kilometres between the towns of Tantan Plage and Dakhla. This section lies partly on Moroccan territory, but also largely on the territory of Western Sahara. Similar to Tangier and Nador, repressive policies, raids and forced displacements into the interior of the country are also on the rise here. During the Covid 19 pandemic, migrants were detained in isolation centres for months, as documented by a group of civil society organisations.

Although the shortest route to Fuerteventura is only 100 kilometres long, the crossing is far longer and more dangerous than via the West Mediterranean route. Here too, people are often intercepted by the Moroccan navy and taken back to Morocco, including those in distress at sea. The survivors are then taken to other parts of the country.

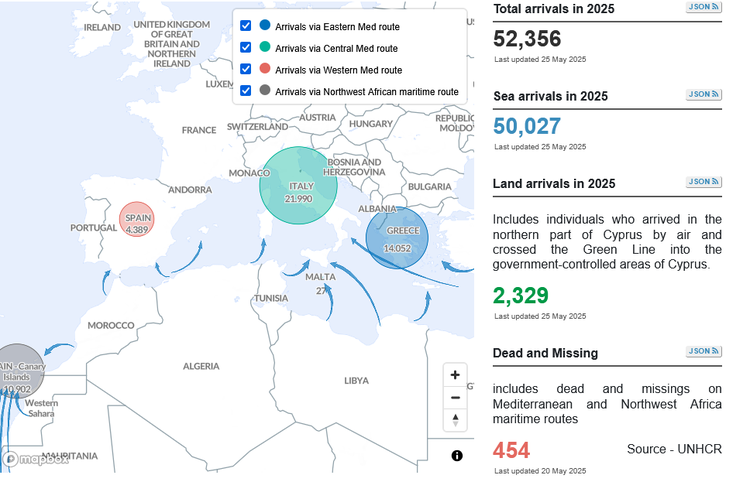

A few thousand people, mainly from Morocco itself, reach the Canary Islands via this route. The majority of the more than 40,000 people who arrived in the Canary Islands in 2024 used the even more dangerous route, against the current of the Canary Current, from Mauritania and Senegal.

(C) UN 2006

5. Migrants in Morocco

5.1 The Socio-economic Situation of Migrants in Marokko

The number of sub-Saharan migrants in Morocco has risen significantly since 2000. Their number is estimated between 50,000 to 200,000. In two legalisation campaigns in 2014 and 2017, around 50,000 people were granted a residence permit. These developments have led to increased interaction between locals and immigrants. However, social participation is generally not guaranteed for migrant and racialised groups. Racist prejudices and discrimination are widespread.

Labour

One specific hurdle is the limited access to the formal labour market. Unemployment has risen sharply in recent years and stands at 30% in some regions. In any case, two thirds of all employment relationships are informal. While also many Moroccans are struggling with limited access to formal exployment, the restrictive legal framework and racist practices make access for black Africans even more difficult. There are only agreements with two neighbouring countries, Algeria and Senegal, to facilitate access to the labour market for their respective nationals. Moroccan nationals are generally preferred to all other African migrants - in the case of filling a vacancy with a non-Moroccan, the employer must prove that no Moroccan applicants were fit for the position. There are exceptions to this principle of préférence nationale, which is also applied to third-country nationals in the EU, for people who have obtained a residence permit as part of one of the two regularisation campaigns (2014 and 2017). In practice, however, it is difficult to assert this privilege.

Access to justice is difficult in this and other contexts. Most migrants are therefore dependent on the informal sector. Here, low wages, dangerous working conditions (e.g. in the construction sector) as well as abuse and exploitation (especially when working in private households) are common.[7] Nevertheless, some Black women have managed to find a job with a regular income, for example in one of the many call centres. Half of regular Black migrants are women.

Health

Access to healthcare services is severely restricted for most migrants. For people without financial resources and without residence papers, public and private medical care is inaccessible. Most inpatient care in Morocco is provided in private clinics. Only in emergencies do migrants spend their savings on medical treatment. Some humanitarian organisations cover the costs of urgent treatment on the basis of vulnerability criteria.[8] This does not cover the need by far. The reform of the healthcare system, which was introduced in 2021, has led to health insurance for Moroccans, but migrants with informal status have been excluded from the system.

Housing

For people without papers, access to housing is considerably more difficult. In the urban centres on Morocco's Old Atlantic coast, such as Casablanca, Agadir, Ait-Melloul, Inzegane and Rabat-Salé, people from Central and West Africa usually live in poor neighbourhoods dominated by migrants, with a high degree of insecurity. In cities in border regions such as Nador or Oujda, the accommodation conditions are particularly precarious and constantly under threat of raids by the security forces.

Raids and Assaults

In the large cities in the west and north of Morocco, black migrants are often arrested on the street. However, raids also take place in migrant neighbourhoods. Most of those taken away by the police are deported to remote areas, to the border areas around Oujda, but also to places in the south. In the course of their stay in Morocco, some migrants are arrested and deported several times: two people from Mali reported that they had been deported to the Oujda region around 30 times over the last 10 years and deported from there to Algeria several times. However, they always made it back to Morocco despite the great dangers.

Black migrants in particular (especially those from West, Central and North-East Africa) face violent attacks in addition to verbal hostility. Many report violent attacks, assaults and robberies. However, the biggest concern for migrants is the constant risk of arrest by the police. This also affects refugees who have already been granted protection status by the UNHCR or whose application for protection is still being processed by the UNHCR. Officially, the security forces are required to regard proof of an asylum application to the UNHCR as proof of regular residence. In practice, however, abductions and deportations of asylum seekers occur regularly.

Morocco signed the Geneva Convention on Refugees back in 1956. In a memorandum between the Kingdom and the UNHCR, the latter is recognised as having the authority to examine asylum applications. People who are granted protection status by the UNHCR are to be granted a residence permit by a Moroccan state commission in accordance with the Geneva Convention, ratified in 1957. Immigration and asylum legislation has been announced since 2013, but there is still no national asylum law and no state authority to examine applications.

5.2 Forms of Self-organisation and Resistance

The Camps

Self-organised structures are enormously important for the survival of Black migrants. These have repeatedly formed at various hubs. Since 2013, there has been a camp near the main railway station in the city of Fez that housed up to 6,000 residents. It was destroyed by Moroccan security forces in 2016. Subsequently, a new camp was built in Casablanca, near the bus station in the Ouled Ziane neighbourhood. People on the move came together here under adverse conditions to recover from their time at the borders in the north or from the forced displacements. However, the hygiene and safety conditions were poor. After the camp burned down several times (most recently on 18 February 2024), it was demolished by Moroccan security forces. Since the end of 2024, there has been a construction site here, so it is no longer possible to occupy the square in front of the bus station. Other places that fulfil similar functions and in which important communities have formed are Agadir, Inzegane, Ait Melloul (Souss-Massa region) and Beni Mellal (Beni-Mellal - Khenifra/Middle Atlas region).

In these camps, migrants use cultural forms of expression such as music, theatre and art alongside their protests to keep their experiences alive and communicate their resistance to the difficult living conditions. They use creative means to create new, albeit precarious, identities, promote a sense of community and raise public awareness of their situation. Some develop new religious sensibilities that help them to strengthen their self-confidence and draw strength in difficult times.

The migration route through Morocco has been described in several autobiographical books. Emmanuel Mbolela lived in Rabat in 2005, where he founded the Association of Congolese Refugees and Asylum Seekers (ARCOM). In his book My journey from Congo to Europe, he reports on the precarious conditions in terms of housing, health, education and work, in addition to the daily experience of raids and deportations. In those years, Fabien Didier Yene also repeatedly tried to cross the border fortifications of Melilla. In his book, Bis an die Grenzen, he describes how he was repeatedly turned back, picked up, deported to the border and once left behind with a few others in the middle of the desert. In 2008, Yene was elected chairman of the Cameroonian emigrant community in Morocco and worked in various human rights organisations for the right to freedom of movement.

The camps in the forests of Mont Gourougou, off Melilla, and the forest of Belyounech off Ceuta have been history since the massacre of 24 June 2022. Isabella Alexander-Nathani has created a sensitive memorial to these camps in her book Burning at Europe's Borders. She describes a community of young men from Guinea who are preparing to attack the fences of Melilla. Alexander-Nathani also describes the racism and deportations that reached a peak in 2005 and 2013. In particular, however, she addresses the connection between the experiences and the irrepressible will and suffering of Black migrants as "Burning Yesterday for Tomorrow". On their years-long journey, Black migrants find themselves in "liminal spaces" and develop new ways of relating and subjectivities. Since the massacre of 2022, the route from Oujda via Algeria to Tunisia has become more important for those who are still trying to reach Europe. But this route has also become increasingly difficult and expensive, and conditions in Tunisia have been untenable since 2023. Quite a few people have returned to Morocco from there.

The film This Jungo Life (2024) by David Fedele and the Jungo of Rabat provides a poignant insight into the lives of some young men from Sudan

Everyday Resistance and Protest

In her field research (between 2016 and 2020), Annélie Delescluse looked at the practices and ideas of self-defence of migrants from West and Central Africa in Morocco. They invent, differently and creatively, individual or collective forms of resistance to survive and denounce dehumanisation and oppressive mechanisms. Most of them live in the poor neighbourhoods of the big cities. Their everyday lives are characterised by cohesion and solidarity with one another, but also by social precarity and the historically rooted racism of Moroccans,[9] which is still widespread in popular perceptions.

Political demonstrations are a frequently chosen form of protest. Here, migrants raise their voices to draw attention to their situation and demand change. For example, in 2012, a peaceful protest movement emerged in response to human rights violations by state security forces in the Takkadoum district of the capital Rabat, from which the migrant self-organisation ALECMA developed. This and other moments of collective mobilisation have a central place in the consciousness of migrant movements in Morocco. Hunger strikes are also used to draw attention to grievances and the plight of migrants and to exert pressure on the authorities. Sometimes there has also been violence against property, as a reflection of the violence they invariably experience from the security forces and authorities. The protests often relate to global movements such as "Black Lives Matter" and aim to draw the attention of the international community to their situation. Demonstrations are organised and public statements made to draw attention to their situation and hold the perpetrators accountable.

Delescluse's (2023) observations in the Douar Doum neighbourhood in the capital Rabat are a significant example of the realities of life for migrants in Morocco and how they are shaped by collectivity. Douar Doum is a popular, but also poorer neighbourhood where many migrants from sub-Saharan Africa live. Residents' access to basic services such as water, electricity and sanitary facilities is limited. The migrants here have formed a community of solidarity in which they share resources and information and create a sense of belonging. Religious gatherings and collective practices also play an important role in the lives of migrants in Douar Doum, giving them psychological resilience and social support.

An important example of collective action by migrants against repression was the protests surrounding the death of Senegalese Ismaila Faye on 8 August 2013. Faye died as a result of police violence during an arrest in the northern Moroccan city of Tangier. He reportedly died as a result of a serious head injury sustained when he was thrown from a police vehicle while trying to show his residence permit. The protesters refused to hand over Faye's body to the police and instead carried it through the streets to draw attention to the circumstances of his death and demand justice. This case attracted international attention and was covered by various media outlets. Human rights organisations and activists called for an investigation and accountability for the officers involved.

6. Migration Policy in Morocco

Morocco's migration policy is a complex mixture of different dispositions under the claim of national sovereignty. Since 2013, Morocco has pursued a new approach to migration policy, the new migration and asylum policy (Nouvelle Politique d'Immigration et d'Asile, NPIA), which was implemented through the Stratégie nationale d'immigration et d'asile (SNIA). Among other things, the SNIA was characterised by the two major regularisation campaigns carried out in 2014 and 2017. De facto, this affected around 50,000 people; mostly African migrants, but also, for example, Filipino nationals, mostly women, who worked in the household sector in the big cities. None of the people who came to the country later were able to benefit from this and, as described earlier, there is still no functioning asylum system today.

Since 1999, when the EU launched its first "action plan", migration policy has been essentially characterised by foreign policy objectives.

Towards the north, Morocco has managed to use black migrants, but also the Harraga from the country itself, as a manoeuvring mass in the negotiations with the EU. They revolved around political recognition and money, but also around the Western Sahara issue. In June 2013, the Moroccan government was the first country in the Mediterranean region to sign a "mobility partnership" with the EU, which contributed significantly to the reform of the migration laws (NPIA) that were announced three months later. From 2014, the EU provided €232 million for this new migration policy, including migration and border management; however, for Morocco, these negotiations were more about gaining prestige than money. In fact, the Western Sahara issue blocked cooperation with the EU until 2019. For more information, see chapter 7.

In dialogue with the EU, and after billions in payments, Morocco returned to cooperate with the EU in 2019 and began to limit boat passages to the north through raids and deportations, as well as by arming the coast guard. By joining the Abraham Accords, Morocco was able to slip under the shield of the US-Israeli alliance. These treaties recognised the Moroccan annexation of Western Sahara. It was now only a matter of time before the Spanish government was also prepared to take this step in 2022. This resulted in the massacre in Melilla, which finally ended the assault on the fortifications of the exclaves. Most recently, France confirmed Morocco's role in the Western Sahara conflict and was rewarded in October 2024 with economic contracts and a readmission agreement regarding Moroccan migrants in France.

Towards the west, in competition with Algeria, Morocco is foregoing the economic and energy-policy-related advantages of North African co-operation, because the demarcation against Algeria and the annexation of Western Sahara have virtually become a state doctrine. Morocco has fortified the border with Algeria with sand walls and military posts, but at the same time has kept it porous: both for smuggling, which has become the livelihood of hundreds of thousands of people and whose closure would significantly increase the risk of uprisings in the periphery, as well as for black migrants, who are still important as a bargaining chip vis-à-vis the EU and whose departure to Algeria is desired. On the other hand, Morocco is expected to face problems of demographic transition in just a few years' time, in which black migrants will be welcome as a labour force.

Towards the South, Morocco was isolated for years due to the Western Sahara issue and was only able to return to the African Union in 2017. The negotiations with the EU were associated with a presitge gain, with the reorientation of migration policy in 2013 also playing an important role. However, this bonus has now been spent; NIPA has been going backwards again since 2018.

In recent years, Morocco has become one of the most important investors in Africa, particularly in West Africa. The country pursues an active South-South co-operation policy, which is strongly supported by the Makhzen. The target areas for investment were Côte d'Ivoire, Senegal, Mali, Nigeria, Ghana and Gabon. The main focus was on the banking sector, Maroc Telecom, the phosphate industry, the construction sector and on the Royal Air Moroc, with Casablanca aiport being a major hub for flight connections between West Africa and Europe.

Morocco is also trying to position itself in the fight against terrorism and drug trafficking. The country has established military co-operation with various African states. Since the founding of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) including, Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso, Morocco has seen itsel in an advantage over Algeria and has offered the military regimes concerned extensive cooperation, including the expansion and utilisation of the only port in Western Sahara, Ad-Dakhla.

The close cooperation between Morocco and the United States shows overlaps in the interests of both countries. Morocco is striving for a regional leadership role, while the US wants to strengthen its presence in North Africa (given the ever-expanding Chinese and Russian interests in the region). The increasing military support and co-operation agreements between the two countries illustrate their strategic partnership. The development of relations with Israel since the Abraham Accords (2020) marks a further step in Morocco's geopolitical development. The signing of various agreements and initiatives between Morocco and Israel shows the deepening of their relations in the areas of security, defence and trade. In addition to their geopolitical interests, the two countries are united by the fact that hundreds of thousands of Israel's population are of Moroccan descent.

In the balancing act of his foreign policy, the Makhzen has to weigh things up time and again; among the population, there is traditional sympathy for the Palestinians on the one hand and traditional resentment towards black people on the other. At the beginning of April 2025, there were mass protests against the Gaza war in Casablanca and Rabat and against the role of the USA in this war. It is therefore no coincidence that Makhzen's policy has been accompanied by a renewed increase in internal repression and control since 2018, with the Rif uprisings and the sluggish implementation of reconstruction programmes in the earthquake regions, but also the regime's foreign policy manoeuvres, which have no support among the population.

7. Externalisation Policy of the EU

Due to its geographical location, Morocco has been a central target of European migration control and deterrence strategies since the early 1990s and is considered a testing ground for the externalisation of European border policy. Important milestones in this development are the closure of the EU's southern border in 1992, turning the Strait of Gibraltar into a dangerous escape route; the mass collective crossings of the border fortifications of Ceuta and Melilla in 2005, whereupon Spain declared a "migration crisis"; the conclusion of a mobility partnership with the EU in 2013; the increased border armament and implementation of raids from 2018, financed by European funds; and finally the deadly border massacre in June 2022 on the border between Nador and Melilla. In all of this, Morocco is not just the object of European defence measures, but a player with its own interests. This is about Morocco's position as a regional power and the Western Sahara issue, but also about economic interests and the remittances of migrants.

7.1 Migration to Europe

In the 1960s and early 1970s, there were bilateral labour recruitment agreements between Morocco and other Western European countries such as Italy, Turkey and Yugoslavia. An agreement on the recruitment of labour was concluded with Morocco in 1963. Since the 1990s, Morocco has been the country of origin with the highest number of immigrants in the EU - ahead of Turkey; 3 to 4 million Moroccans live in emigration, and 84% of them live in the EU. After the recruitment stop in 1973, the bottleneck of family reunification, marriage or a life in Europe without papers under the constant threat of deportation remained the only choice for most.

In May 1990, under pressure from the EU, Spain also introduced a visa requirement for Moroccans. In the summer of 1992, around 30,000 people crossed the Strait of Gibraltar on small boats, which in the following years became the largest mass grave in post-war Europe: Between 1991 and 1996, between 2,000 and 4,000 people probably perished in the Strait of Gibraltar alone. Another route to Europe led to the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla, where fences and border fortifications have been erected since 1994. These were collectively overcome by a large number of migrants in 2005, which triggered hectic reactions from the Spanish and European side (GAMM, Rabat process, see below). The climax of the struggle around and push-backs from these enclaves was the Melilla massacre of 24 June 2022, in which, according to Moroccan authorities, at least 23 migrants died as a result of border violence and more than 70 went missing.

In the years after 2011, migration movements and therefore Europe's attention shifted towards Libya and the central Mediterranean. It was only in connection with the unrest in the Rif from autumn 2016 that the trend reversed again. In 2018 alone, over 64,000 migrants arrived in Spain, a quarter of whom were Moroccans.[10] However, the UNHCR's figures are inaccurate: almost two thirds of the people who arrived in Spain, mainly from Morocco, did not apply for asylum but went into hiding. Only one in ten of the boat people from Morocco and only one in twenty from Guinea or Mali applied for asylum. In many Moroccan families, transnational networks have developed to facilitate transnational migration, such as the trading of labour contracts, joint investment in the travel expenses of an "economic martyr" or family reunification through marriage to a person already living in Europe.[11] The state has promoted emigration from the outset because the migrants' remittances are a significant source of foreign currency and secure the income of many families.

In 2018, Morocco once again found itself at the centre of European defence policy. The Spanish sea rescue organisation SASEMAR withdrew. As in the case of Italy and Libya, the EU and the Spanish government transferred 170 million Euros to Morocco, partly earmarked for the establishment of a Moroccan search- and rescue (SAR) system, and prohibited their own aircrafts and ships from carrying out rescue operations in Moroccan waters. In the same year, 2018, the ICMPD launched a four-year Border Management Programme (BMP) with the aim of reducing the risks of migration by restricting it. ICMPD supplied equipment to monitor the borders.[12] More effective border protection in Morocco and Tunisia was also to be ensured institutionally. The passage across the Strait of Gibraltar was also largely closed by the Frontex operation Indalo. Migration routes shifted to the Atlantic route to the Canary Islands, where three quarters of arrivals in Spain are currently recorded. The Alarm Phone reported in March 2022 that the withdrawal of Spanish search- and rescue assets had also led to an "invisible wall on the Atlantic". According to the Spanish organisation "Caminando Fronteras", 9,757 people died on this route in 2024.

7.2 Externalisation 1993 - 2011 : The Diplomatic Period. IOM and ICMPD Get Down to Business.

European countries have been working on a common police and security apparatus since the 1970s. The pacemaker of the common border controls at the external borders and the common police system was the opening of the inner-European borders in the Schengen Agreement in 1985.[13] The EU was founded in 1992 with the Maastricht Treaty and in the following year, the EU made the principled decision to seek expansion to the east and to seal itself off from the south. In return for controlling unwanted migration, the states in the east and south-east were offered the prospect of accession - but not the states south of the Mediterranean, which were not even offered a generous visa regime.

The negotiations with Morocco followed the path of Spain, which had already concluded a readmission agreement with Morocco in February 1993 and which also provided for the readmission of third-country nationals.[14] Since then, Morocco has concluded bilateral readmission agreements with a number of countries.[15] However, over the last 30 years it has consistently and cunningly avoided concluding such an agreement for third-country nationals. This would require Morocco to conclude a chain of further readmission agreements with countries of origin and visa regulations, which would significantly impair Morocco's relationship with the West African states. However, Morocco has accepted the construction of high fences around Ceuta and Melilla and informal deportations from these exclaves.

Further stages in the negotiations were the EU-Mediterranean Partnership of 1995 and the special EU summit in Tampere in 1999, at which an attempt was made to define a common European asylum and migration policy, which was to be implemented in bilateral and EU agreements with the so-called sending and transit states. In the run-up to this summit, the EU Council had already presented an action plan for Morocco16 , which can be seen as a prototype for numerous other such papers.

In 2005, there were hundreds of collective border crossings at the heavily guarded fences of Ceuta and Melilla. Once again, Spain became the pacemaker of cooperation with Morocco; by mutual agreement, the border fortifications around the exclaves of Ceuta and Melilla were further expanded. Spain also paid for Moroccan police raids in the camps around the enclaves and the deportation of people across the border to Algeria into no man's land.[16] This "migration crisis" gave rise to the "Global Approach to Migration" (GAM, GAMM since 2006), which became the "backbone of EU migration policy" in the years that followed.[17] One year later, a multinational dialogue process followed with the Rabat Process, in which the ICMPD took over the leadership of negotiations. The conduct of negotiations was thus shifted directly from the diplomatic sphere to a think tank. The ICMPD not only provided expertise and negotiation management beyond the diplomatic sphere, but also supplied technology and equipment at short notice. Tunisia and later Morocco were persuaded to make it a criminal offence to leave their territory.

The IOM also found an "entrepreneurial field" or "testing ground" for the expansion of its management practices in Morocco, whereby, in addition to information campaigns, programmes of "voluntary" return were carried out. Since then, ongoing insecurity and arbitrariness have characterised the IOM's position in the North African border regions.[18]

7.3 Externalisation 2011 - 2017 : The Consequences of the Arab Revolution

The Arab Revolution thwarted the EU's Mediterranean strategy. The fall of the dictator Ben Ali in Tunisia, who had made it a criminal offence to leave his country, opened the way to Lampedusa, and the fall of Gaddafi in Libya led to the opening of the central Mediterranean route. In particular, however, the war waged by the Syrian ruler Al Assad against his own people generated sustained refugee movements that are still relevant today.

The royal regime in Morocco survived the revolutionary period relatively unscathed and was not under as much pressure from the population as the government in Tunisia, for example. In June 2013, the Moroccan government was the first country in the Mediterranean region to sign a "mobility partnership" with the EU. The accompanying declaration stated:

"On illegal migration, the EU and Morocco will work together to better tackle smuggling and trafficking networks and help victims. They will also work closely together to help Morocco set up a national system for asylum and international protection."

In fact, three months later the king announced a reform of the migration laws and the EU provided 232 million Euros from 2014 for the new migration policy, including migration and border management, whereby the EU funds were less important for Morocco than the gain in prestige.[19]

The first EU programmes to finance migration prevention, which were set up after Tampere[20] , were replaced in 2014 - 2017 by the European Neighbourhood Instrument, which provided Morocco with over 800 million Euros, mainly as budget support. In 2016, the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF for Africa) was also launched, which provided additional and extensive funding for shielding off against the large migration movements from 2015 onwards.

Morocco was not in the EU's focus at this time. This changed a short time later when the uprising in the Rif in 2016 led to an increase in the number of people travelling to Spain, although Morocco's relations with the EU had deteriorated at this point due to the Western Sahara issue.

7.4. Externalisation since 2018 : Armament, Raids and a Massacre

In view of the high number of boat arrivals and mass crossings of the Ceuta border fence in 2018, the EU deliberately refrained from taking a clear position on the Western Sahara issue because it was dependent on cooperation with Morocco to control migration movements. In this context, it also accommodated Morocco's demands for equipment. The EU's dialogue with Morocco was resumed in 2019. Looking back, the European Council wrote in its "Update on the Field of Play" in July 2023

After several years of standstill (as part of the general freeze in relations between the EU and Morocco), the dialogue was formally resumed in 2019 (Association Council of 27 June 2019). Morocco recognises migration and security as key areas for cooperation with the EU. Morocco has made considerable efforts to significantly reduce the flow of irregular migrants entering the EU via the Mediterranean. However, the number of irregular arrivals of Moroccans and from Morocco remains high, especially on the route via the Canary Islands.

In August 2019, the Directeur de la Migration et de la surveillance des frontières at the Ministry of the Interior, Khalid Zerouali, gave an interview to the Diario as an expression of the thaw in diplomatic relations between Morocco and the EU in summer 2019. He emphasised that Morocco had successfully curbed irregular migration to Spain for over 15 years. Between 2014 and 2015, allegedly 93% of all crossings were prevented and numerous smuggling networks dismantled. However, migration pressure increased significantly in 2018.

The dialogue was underpinned by extensive arms deliveries. A report in December 2019 stated:

In recent months, Morocco has been rapidly upgraded by the EU for border surveillance. Morocco is currently receiving over 1,300 vehicles from the EU, mostly off-road vehicles, prisoner transporters, motorbikes, ambulances and refrigerated vans, 1,400 computers and tablets, extensive communication, radar, surveillance and scanning equipment as well as drones. Recently, the EU Court of Auditors criticised the fact that Morocco is a bottomless pit when it comes to receiving funds and materials: there is no accountability and no monitoring of expenditure, purchases and use.

The European Commission states that it paid more than 2.1 billion Euros between 2014 and 2022 to Morocco: 1.5 billion in the form of bilateral contracts and under the EUTF and further 631 million under the NDICI (Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument), which has replaced the EUTF since 2021. The complexity of the European programmes, the linking of European and bilateral programmes and the implementation from special funds by IGOs and NGOs make it difficult to create a precise overview. The list in Annex 1 of the Draft Action Plan Morocco of 18 April 2022, which was published by Statewatch, provides some indications.

Until 2021, the EUTF was the EU's most important instrument for "supporting Morocco in the area of migration". Regional and bilateral agreements provided 234 million euros for this area. 77% of this money, namely 178 million Euros, was channelled into integrated border management, border management and the fight against smuggling and human trafficking. The implementation of the EUTF projects will run until December 2025. 150 million Euros were made available under the NDICI in 2022 for four years with the aim of "strengthening EU-Morocco cooperation" and "dialogue on migration". Most recently, a "Southern Neighbourhood migration package" worth 279 million Euros was adopted in June 2023, which related to combating smugglers and human traffickers, strengthening border management and supporting voluntary returns.

The EU's empty rhetoric, which always emphasise humanitarian aspects and the fight against people smugglers, conceal hard facts: the arming of border authorities, the hunt for people trying to cross the sea and raids against black African migrants in northern Morocco.

As already described in section 4.2.2, the policy on the borders of the Spanish exclaves has come to symbolise the European-Moroccan policy. Since March 2020, Morocco has kept access to the land border to Ceuta and Melilla closed. Originally justified as a measure to contain the Covid pandemic, the Moroccan authorities delayed the opening in order to exert pressure on Spain over the Western Sahara issue. The separation of numerous families and the interruption of small-scale trade, which was lucrative for both sides, were accepted as a result.

On 17 May 2021, the Moroccan security forces temporarily relaxed the controls off Ceuta and allowed 6,000 people to pass, who reached the enclave by swimming and in rubber dinghies. At the beginning of March 2022, 850 people managed to cross the fence in Melilla. The Sanchez government understood the message and began to reconsider its position in the Western Sahara conflict. In return, Morocco accepted repatriation flights from Spain. In April 2022, Pedro Sánches visited Rabat and confirmed the change in Spain's position.

On 24 June, the Moroccan security forces showed their gratitude by staging the massacre in Melilla. Subsequently, there were various diplomatic efforts to capitalise on what had happened. While Pedro Sánchez spoke of an "attack on the territorial integrity of Spain" and tried to get NATO involved in the problem of Ceuta and Melilla, the Moroccan government accused Algeria: The "attackers" had entered Morocco via the Algerian border and had "taken advantage of Algeria's deliberate laxity in controlling its borders with Morocco", a statement from the Moroccan embassy said. The rush to the border, which involved up to 2,000 migrants on Friday, indicated "a high level of organisation, a planned approach and a hierarchical structure of battle-hardened and trained leaders with experience in conflict zones." The message: Black migrants are attacking NATO and are enemies that Morocco and the EU must fight together.

But even after the massacre, the routes from Morocco are not yet closed. By sea or by land, refugees still transit Morocco to get to Europe, according to al-Jazeera in October 2023. Morocco claims to have stopped more than 78,000 migrants on their way to Europe in 2024, 58% of them from West Africa and 12% from North Africa.[21] This primarily concerns the Atlantic route, where Pedro Sanchez described the cooperation with Morocco as "exemplary good". More than 18,000 people have been rescued from their boats.

While the groups of black migrants have given up running against the fences of the exclaves, Moroccan and Algerian youths are still trying. A newspaper report from August 2024 stated:

According to Spanish authorities, thousands of people are currently trying to reach the Spanish North African exclave of Ceuta illegally and thus enter the EU. Since Thursday, an average of almost 700 refugees have attempted to reach the coastal city by swimming or in small boats. The migrants, who mainly come from Morocco and Algeria, have also taken advantage of the dense fog over the sea.

Footnotes

-

The colonial legacy includes regional disparities with neglected peripheral regions (especially the Rif and Atlas Mountains), a detached administrative apparatus, the authoritarian structure of the state, the French-speaking elites and an economic structure geared towards extraction.

↩ -

Morocco controls 80% of the territory of Western Sahara, including the entire coastline with its rich fishing grounds and valuable phosphate deposits.

↩ -

In 1991, Morocco and the Polisario Front (a liberation movement seeking self-determination for Western Sahara) agreed on a ceasefire brokered by the United Nations to hold a referendum on self-determination. To date, this referendum has not taken place. Morocco rejects in principle any vote on self-determination that would include independence of Western Sahara from Morocco as an option. In December 2020, then US President Donald Trump rejected the United Nations-sponsored process of self-determination for the Sahrawis by recognising Morocco's sovereignty over Western Sahara. Since then, Morocco has been pressurising its Western allies, including Spain and France, to do the same and has been increasingly successful in its efforts.

↩ -

de Haas, Hein: Morocco: Setting the Stage for Becoming a Migration Transition Country?, Washington DC, Migration Policy Institute 2014; see also the series of articles by Hein de Haas on BpB (2009)

↩ -

https://ffm-online.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Ausgelagert.pdf p.35

↩ -

Fuchs, Eva (2014): Haraga and "economic martyrs" in transnational Moroccan society, Ethnoscripts 16 (2): p. 107; https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/61345/ssoar-ethnoscripts-2014-2-fuchs-Haraga_und_Wirtschaftsmartyrer_in_der.pdf;sequence=1

↩ -

See the reports by Marie Pascale Rouff in Archipel 328 (September 2023) and Archipel 339 (September 2024)

↩ -

In April 2024, UNHCR published a brochure Mapping Protection Services, a route-based approach, with regional addresses where migrants can seek help.

↩ -