From Hell to Hell: Sudanese Youth Criminalized in Greek Prisons

September 15th, 2025

By Ibrahim Izzeldeen*

Youth From War to Prison

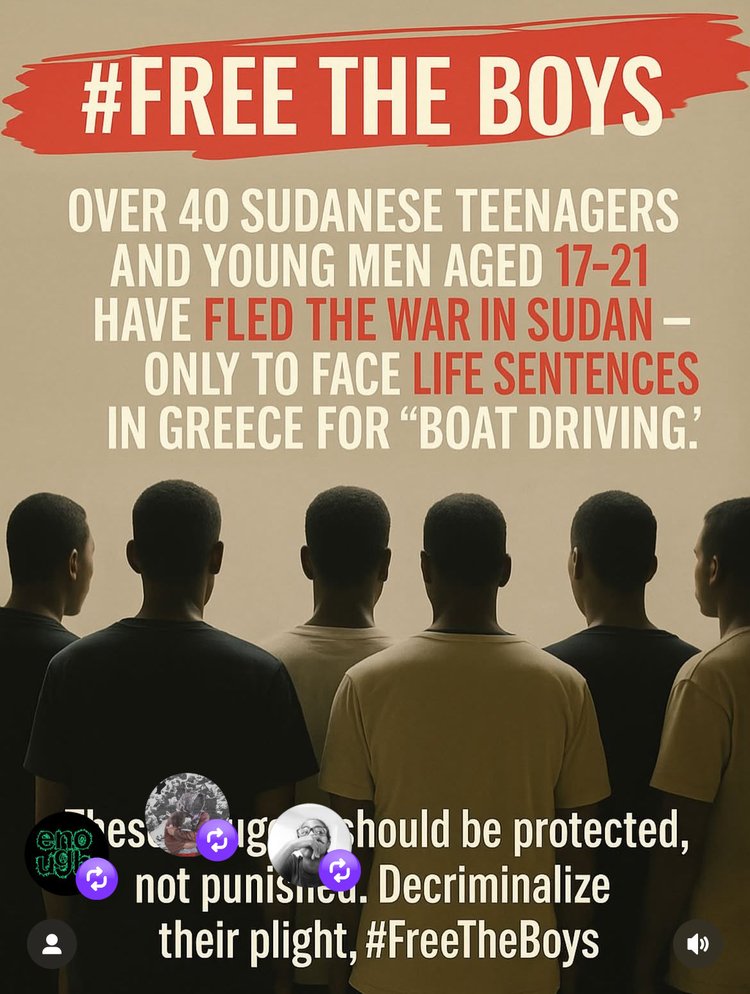

In Greek prisons from Crete to Volos, more than 200 Sudanese teenagers and young men sit behind bars. Their alleged crime is not violence, theft, or exploitation. It is survival. Fleeing one of the world’s deadliest wars, they crossed the Mediterranean seeking safety—only to be prosecuted as “smugglers” under Greece’s sweeping anti-smuggling laws. Most are between 17 and 26 years old, boys on the threshold of adulthood. Instead of schools and apprenticeships, their youth is being spent in prison cells thousands of kilometers from home.

War in Sudan: The Push Factors

Since April 2023, Sudan has been consumed by a brutal war between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF). What began as a power struggle in Khartoum quickly escalated into nationwide devastation.

According to the United Nations, more than 10 million people have been displaced—the largest displacement crisis in the world today. Cities such as Khartoum, Omdurman, El Fasher, and El Geneina have been reduced to rubble. Mass killings, sexual violence, and forced recruitment campaigns have targeted young men in particular. Education has collapsed, livelihoods have vanished, and families have been torn apart.

For many Sudanese youth, flight was not a choice but the only path to survival. Yet escape has rarely meant safety. Many who managed to reach Greece—after harrowing journeys through Egypt and Libya—now find themselves criminalized for the act of steering a boat, handing out water, or even holding a GPS during the crossing.

Criminalization at Europe’s Borders

Under Greek law, steering or assisting in boat crossings is classified as smuggling, punishable by sentences of up to 25 years per person transported. In practice, this means that a 17-year-old refugee who touches the wheel of a dinghy can be prosecuted as a criminal trafficker.

“Since 2014, if any one of us was forced to steer the boat or help the others, they call us criminals,” explained J, a young Sudanese man currently imprisoned in Crete. “Most of us had no choice—either cooperate or risk our lives at sea.”

Human rights groups have long argued that Greece’s framework is not dismantling smuggling networks but targeting the very refugees it claims to protect. According to a 2023 report by Refugee Support Aegean (RSA), trials often last less than an hour, with inadequate interpretation, minimal legal defense, and an almost automatic presumption of guilt.

“These laws are formulated so broadly that any act during a border crossing—holding the GPS, distributing water, or simply being near the helm—can be treated as smuggling,” said Julia, a member of de:criminalize, a European activist network. “The state uses this to create scapegoats while hiding its own responsibility for deaths at sea.”

Greece currently holds more than 2,300 migrants accused of smuggling, many of them Sudanese minors at the time of arrest.

Life Behind Bars

Inside prison, the cost is measured not only in lost years but in broken spirits.

“We live behind bars, not as refugees seeking safety, but as accused criminals for crimes we never chose,” said J. “Many of us have suicidal thoughts because of the lack of a future and separation from our families.”

Psychologists report high levels of trauma, depression, and hopelessness among Sudanese youth in detention. Families back home, already displaced by war, struggle to stay in touch. Some cannot even confirm whether their sons are alive.

Mustafa, a Sudanese activist living in Greece, described the ripple effect: “Parents and siblings are desperate. They try to send money, letters, or moral support, but communication is limited. Many of these young men are alone, and families feel powerless to help.”

⸻

Four Sudanese Boys, Four voices and Four lifes.

Bada Ruman Steven, 19

Bada fled Sudan after losing his parents in the war. He tried to survive with his sisters in Egypt, then Libya, where he worked as a cleaner under exploitative conditions. Forced at gunpoint to hold a GPS during the crossing, he was arrested upon arrival in Greece. Six months later, he remains imprisoned, separated from his sisters. “I am not a criminal. I am a victim of war,” he said.

Mousab, 19

Coerced into driving a boat for 12 hours under threat from smugglers, Mousab was sentenced to 25 years in prison. He has not spoken to his family in seven months. “I spoke out, but no one wanted to listen. I’m innocent of what they accuse me of.”

Suleman Mazen, 18

After losing his family in Sudan, Suleman endured overcrowded detention in Libya before reaching Greece, where he was immediately arrested. “You are my voice and my strength,” he said in a letter from prison. “We are only human beings trying to survive in life.”

Chol Hani Zacheria, 17

The youngest among them, Chol worked odd jobs in Libya to afford passage to Europe. Arrested upon arrival in Greece, he was imprisoned with older men. Soon after, his mother died of a panic attack upon hearing of his imprisonment. “We are not criminals,” he pleaded. “We are children of war and destruction, searching for a safe place.”

Solidarity in a move

Across Europe, solidarity networks have mobilized under the banner of #FreeTheBoys. Lawyers, activists, and diaspora communities are fighting for the release of Sudanese prisoners and for reform of anti-smuggling laws.

Mustafa described grassroots efforts: “We organize awareness events, fundraising, and letter-writing sessions. We connect with lawyers to track trials, support those released in applying for asylum, and help them find housing. It is all about making sure they know they are not forgotten.”

In Athens, the Alma Community provides holistic care to refugees through therapy, art, and community-led workshops. Founder Erinia Tsilafaki explained: “Trauma is not only personal but political, rooted in war, borders, and displacement. Alma is a safe space where refugees are not just recipients—they lead, teach, and shape the community.”

The Legal Battlefield

In early September 2025, courtrooms in Crete became the stage for a rare moment of scrutiny. Fourteen migrants, including several Sudanese boys, faced trial under Greece’s anti-smuggling laws. For the first time, international observers were allowed inside.

Outcomes varied sharply. Four Sudanese were acquitted—the court acknowledging that fleeing war cannot be equated with smuggling. But others, including Egyptians and Nigerians, received sentences ranging from 10 to 25 years.

“Not only is the imposition of criminal sanctions on refugees prohibited under Article 31 of the Geneva Convention,” argued HIAS Greece, “but those who facilitate their own entry for survival are also excluded from the scope of the smuggling offense.”

Activists warn that justice must not depend on nationality or asylum status. “Linking innocence to nationality is dangerous,” noted the Border Violence Monitoring Network. “Justice must be universal.”

Europe’s Migration Dilemma

The plight of Sudanese teenagers in Greece exposes a broader European trend: the criminalization of migration itself.

“Across the EU, borders are militarized,” said Julia of de:criminalize. “Irregular movement is treated as a crime rather than a human right.”

Mustafa added: “It’s not just Greece. Italy, Spain, and others follow the same logic. Young refugees are criminalized while real smugglers remain largely untouched.”

Legal experts argue that the EU Facilitation Directive, which criminalizes assistance in migration regardless of motive, stands in direct violation of international refugee law. Without reform, cases like those of Sudanese boys in Crete will continue to multiply.

Justice on European Trial

The testimonies of Bada, Mousab, Suleman, and Chol illuminate a painful truth: Europe’s border policies are transforming refugees into criminals. Their only “crime” was steering a boat, holding a GPS, or offering water to fellow passengers—acts of survival punished with decades in prison.

“We have done nothing wrong,” said J from his cell. “We are refugees fleeing war. Our only wish was to find safety and support our families. We are human beings, not criminals.”

For now, the fight for justice continues in courtrooms and solidarity networks across Greece and Europe. But as one activist noted, the stakes reach far beyond Crete: “The question is not only whether these boys will be free. It is whether Europe itself can live up to its principles of justice, dignity, and humanity.

*Ibrahim Izzeldeen, based in Berlin, is a social worker, writer, and filmmaker. He is an active voice in the Sudanese diaspora through SudanUprisingGermany and works on issues of border justice and the anti-deportation movement.