"Protecting Borders" From "Illegal Migrants"? More Like Protecting Migrants From Illegal Governments

March 21st, 2022 - written by: S.I. & G.M

By S.I. & G.M., both working in humanitarian organisations in Greece since 2017.

Illegal Immigrants. Illegal Government.

Susanna Reid for GMB: "What's Greece doing about the many migrants who make the dangerous journey towards your islands?"Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis: "Unless you manage to send a clear signal that you protect your borders, more people will try to enter illegally" Good Morning Britain (16.11.2021)

Ther is an entire generation of power-holders, in Greece and Europe, that hails from a political tradition in which the interest of states in asserting and protecting their borders - whatever that is supposed to mean - is an ‘unquestionable right of the nation’, or even worse: it is marketized as ‘common sense’, as something ‘utterly normal’, as something that is nowhere to be found in the ‘list of world’s problems’.

According to Frontex estimates, the number of border crossings into the EU in the first six months of 2021 has increased by 59% (over 61,000 in total) compared to the same period last year. In the words of the EU Agency itself, these border crossings are referred to as ‘illegal’: something that not only does not bear validity under international Asylum Law, but is also an expression of a rather dangerous political strategy in the hands of governments that, through the use not-so-refined discourse nuances and appeals to ‘common sense’, legitimate on a daily basis documented and consolidated illegal practices.

While the misinformed and misunderstood notion of ‘illegal migration’ has been characterising European public debate for years if not decades, the current Greek government has turned the constant condemnation of the movement of refugees towards the country into its flagship rhetorical argument.

The deployment of such rhetorical ruses, with the endorsement of a multitude of associated power-holders both on a domestic and the international stage, is achieving one result above all: the undermining of those fundamental values - such as rule of law, freedom of movement, non-discrimination and equality of treatment - that are the basis of EU‘s principle body of law‘ and political identity.

The restatement of an ‘emergency situation’ that calls for a so-called ‘protection of borders’ through all means at disposal - whether political and diplomatic back-door channels, the diffusion of invasive technology into people’s privacy and through the legitimation of violence upon marginalised people - is not only become an unproblematized normality: it also paves the way for the problematization of what, instead, should be acknowledged as something completely normal and unquestionable, that is the right to freedom of movement and access to international protection.

In other words, while EU states coalesce in claiming their undisputable right to ‘protect their borders’ from displaced people in seek of asylum, freedom of movement and right to asylum itself are becoming now, perhaps more than ever in recent European history, a purely racialised right.

Lathrometanastes: a populist rhetoric long-time in the making Lathrometanastes means ‘illegal immigrants’ in Greek

(Lathrometanastes means ‘illegal immigrants’ in Greek)

The long summer of 2015 marked a turning point with more than one million refugees entering Greece in less than 12 months - sparking the narrative of the so-called ‘refugee crisis’. The unprecedented pace and nature of these border crossings undoubtedly led to changes in political discourse and management of migrants’ reception. The EU and national authorities, especially in the ‘gateway countries’ like Greece, who are seen as the external border to ‘Europe’, responded with the establishment of five hotspot islands in the Aegean.

After the closure of the ‘Balkan Route’ in early 2016, the newly established SYRIZA government - which was also responsible for the most crucial period of the rampant financial crisis - set out the blueprint of what became the current/hotspot approach to asylum management in Greece. These policies were centered around the thirty large-scale refugee camps that were to be established in mainland Greece - most of them still operative to this day.

Alexis Tsipras' leadership eventually suffered a first big blow at the European elections in May 2019, after which snap general elections were called: the winner of both elections, the right-wing party Nea Dimokratia, took charge of Greece during the Summer of 2019.

Despite totalling one of the lowest electoral turnouts in decades, the leadership of Kyriakos Mitsotakis - son of a former Prime Minister himself, brother and uncle of two Mayors of Athens, and expression of the 'moderate' fringe of a traditional-to-extreme right political group - enjoyed the support of a strong representation in Parliament (158 seats over 300) which enabled the formation of a solid majority government.

With the new administration in place, the management of inbound migration that the country had faced since 2015 - and upon which Nea Dimokratia had built an insistent oppositional campaign - became one of the central talking points in the new political debate. In this new political environment, the relentless criticism of the previous government’s performance in asylum reception was consistently, repeatedly, and unapologetically coupled with an undermining of the legitimacy of asylum seekers claims and permanence in the country. It instilled the assumption that displaced people are to be differentiated into ‘real refugees’ and ‘simple migrants trying to exploit the asylum system and generosity of Greek taxpayers. Not to mention, of course, the most dangerous of all rhetorical tropes: the quick and consistent depiction of all displaced people as ‘illegal migrants’.

Examples of such rhetorical framing are numberless, from mild insinuations to explicit stigmatisation. Just for reference, one could recall how ex-Prime Minister, Antonis Samaras, during the 13th Congress of Nea Dimokratia proclaimed that ‘of all the people trapped in hotspots today, the vast majority are no longer refugees: they are immigrants who entered illegally, [they are] illegal immigrants that entered illegally as invaders’.

A statement that was soon backed by the current Minister of Shipping and Island Policy, Yiannis Plakiotakis, in an interview with national television ANT1, stating rather bluntly that ‘there is a question of illegal invasion by immigrants in the country’.

Another habitual user of this rhetorical trope is none other than the Migration and Asylum Minister himself, Mr. Notis Mitarachis, who can boost a long list of unwarranted and unchecked labelling of any attempt at crossing national borders as ‘illegal immigration’. For example, claiming that the (very much criticised and contested) recognition of Turkey as a ‘safe third country’ is ‘an important step in tackling illegal migration flows and the criminal activity of smuggling networks’ or that the August 2021 developments in Afghanistan will not make of Greece a ‘gateway to Europe for illegal Afghan migrants’.

However, Samaras’, Plakiotakis’ and Mitarachis’ claims are not episodical declarations, but just the extreme expressions of an underlying rhetorical framework that extends beyond the frontiers of Greece and is found in all European political discourses - as shown in the mutual support expressed by Prime Minister Mitsotakis with his then Austrian counterpart, Chancellor Sebastian Kurz, towards the common goal of ‘sending a clear signal of a restrictive migration policy to all potentially illegal immigrants’ together with, of course, ‘destroying the smugglers' business model and stopping the drowning of refugees in the Mediterranean’. Unsurprisingly enough, like many other politicians from the right and centre right across Europe, the latter stepped down from his duties as chancellor in October 2021 over a corruption investigation.

However, the widespread normalisation of such bias can be traced back, for instance, back to 2018 when German Chancellor Angela Merkel, in an attempt to promote inter-European cooperation in border management, stressed that ‘the question of fighting illegal migration means we have to strengthen external border protection’. Ultimately, this trend can be traced even further back, to the very design of the so-called EU-Turkey Statement of March 2016, at which core lies the promise that “Turkey will take any necessary measures to prevent new sea or land routes for illegal migration opening from Turkey to the EU”.

Nea Dimokratia remains the most popular party among voters in 2021, but, at the same time, the far-right party Greek Solution (founded in 2016) is now slowly replacing neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party’s role inside the Greek Parliament, after the sentencing of its leaders in October 2020. The public profile of the ruling party is therefore continuously pushed towards the radical right-wing in an attempt to gain a growing audience on that side of the political spectrum, promoting anti-immigration proposals and nationalistic ideals inside the national debate.

In brief, the topic of migration within political and media discussion comes with a plethora of images, emotions and labels echoing negative stereotypes of ‘migration as invasion’. In other words, the portrayal of migratory movements from the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa towards Europe is entrenched with the tendentious distinction between them - the frightening ‘hordes’ of incoming, unknown ‘strangers’ - and us - something like a ‘coven’ of reassuring familiarity - to the extent that the expedient and arbitrary underrepresentation of displaced people is an essential component of their condemnation in public discourse as ‘illegal immigrants’.

Poisoning the conversation: what does ‘illegal’ even mean?

This stigmatising imagery heavily places its focus on ‘Europe’ and in particular its ‘entry points’ such as Greece - creating a picture of these countries as merely a space where 'border security' is supposedly challenged. This language also promotes an incessant investment into the dehumanising efforts of migrants’ identification, control and surveillance - shifting focus away from looking at a much wider global context and the historical and political root causes of why people are forcibly displaced from their homes.

The legacy of the long season of social and political instability in the Eastern and Southern coasts of the Mediterranean since 2011 is a direct product of decades of Western colonisation, meddling and encroachments in countries which Eurocentric outlooks shroud in misunderstanding, misrepresentation and ignorance.

Nowadays, the public framing and depiction of all third nationals as 'illegal migrants' - regardless of any tangible assessment of legal status and compliance with international asylum law - is the result of this well-crafted imagery construction whose only purpose is to generate popular outrage. In Greece, the aim behind this use of provocative discourse can only be to generate momentum for the portrait of the current national leadership as the 'responsible government' - as a leadership that is 'in control'.

Whether from opponents or supporters: even the relentless attempts to criticise the use of 'illegal migration' imagery can only contribute to fuel the discourse itself. In other words, this government (like many others in Europe) is literally poisoning the conversation.

Let us start with the historical cornerstone of Asylum Law: the four treaties and three amendment protocols commonly known as the Geneva Conventions represent the key legislative architecture of humanitarian treatment of victims of warfare and prosecution and spell out international protection in its broader sense. Among these bodies of law, the 1951 Convention and the 1977 Protocol combined define the juridical persona of the holder of refugee status and discipline the duty of sovereign states towards the individuals seeking international protection that are found within their territories. Needless to say, Greece has ratified and acceded to both, in 1960 and 1968 respectively.

Coming back to the dubious conceit that all border crossing into the EU from non-Schengen countries are to be publicly and presumptively, defined as ‘illegal’, the text of the 1951 Convention itself clarifies this very issue with no room for doubt, as stated in its Article 31:

1. The Contracting States shall not impose penalties, on account of their illegal entry or presence, on refugees who, coming directly from a territory where their life or freedom was threatened in the sense of article 1, enter or are present in their territory without authorization, provided they present themselves without delay to the authorities and show good cause for their illegal entry or presence.

2. The Contracting States shall not apply to the movements of such refugees’ restrictions other than those which are necessary and such restrictions shall only be applied until their status in the country is regularized or they obtain admission into another country. The Contracting States shall allow such refugees a reasonable period and all the necessary facilities to obtain admission into another country.

Moreover, it is stated under European and International Law that “no country has the right to prevent asylum-seekers from leaving a country, and it’s illegal to prevent them from entering a country - as is being blatantly done by Greece. The exact legal framework is emphasized in Article 14 – the right to seek and enjoy asylum – of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and in Articles 2, 3 and 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

Coming back to the aforementioned Geneva Convention, its Article 31 clearly states that “[t]he Contracting States shall not impose penalties, on account of their illegal entry or presence” on refugees. Nonetheless, the Greek authorities sentenced a woman in March 2020 to a four-year term for illegal border crossing in an Athens prison after she took a bus organized by Turkish authorities to bring her to the Greek border. This sentence and all the violence that happened in March 2020 in Evros is part of the instrumentalization of people-on-the-move and the general ongoing political game between Athens and Ankara.

In other words, it is inscribed at the very core of internationally recognised Asylum Law that people seeking asylum enjoy immunity from any legal consequence due to the 'irregularity' of crossing national borders away from official entry points. This makes the labelling of ‘illegal immigration’ a completely and utterly unfounded fallacy.

Still, accordance with the relevant legislation rarely holds any importance in front of populist, national discourses. For as long as the general national audience addressed by opportunistic political groups is not informed on, or just vaguely acquainted with the legal framework of international protection, neither can one expect these political groups to be remotely concerned with such fallacies.

Once again, the depth at which the conversation has been poisoned does not allow for a constructive argument with such well-crafted populist narratives. So, one could ask, why bother disproving and rebutting every single one of the nonsenses and vilifications that overflow contemporary political discourse around migration and asylum?

Because, to put it simply, regardless of its ineffectiveness before populist gibberish talk, the meaning and purpose of Asylum Law is relevant.

The international protection system signed in Geneva seventy years ago - born from the experience of European refugees in the 1940s- responded to one crucial mandate in particular: to ensure that people would find refuge and protection against the unchallenged authority of oppressing nation-states.

This is why Asylum Law is always, and must always remain relevant - even when it is Europe itself that is undermining the Convention and its values.

The same applies to the meaning of 'illegal' under international law. It applies to the systematic neglect and discriminatory treatment as regards health care of asylum seekers, including unequal access to Covid-19 vaccines and vindictive use of public health sanctions against people-on-the-move. This system of structural inequalities is further amplified by the increasing lack of food provision and cash assistance to asylum seekers across Greece. It applies to the widespread criminalisation of displaced communities, the shrinking space for civil society organisations and solidarity actors that support these people. It applies to the fortification and segregation of camps from society. And to the unapologetic legitimation of human rights violations, the impunity - if not direct contempt - for the forcible and unlawful deportation performed by Coast Guard officers in the Aegean, as well as Border Police and ‘masked commandos’ in Northern Greece.

All of the above speaks, at the very least, of the dire situation as regards the rule of lawlessness in the country. And of how urgent it is to lay off the discussion over ‘illegal entry points’, and discuss instead how, and to what extent, the actions of the Greek government - much like the EU leadership and many other governments in Europe - constitute a systematic and manifold violation of international humanitarian law.

A system of structural inequalities: health care, social security, employment, food provision and cash assistance

"Everyone has the right of access to preventive health care and the right to benefit from medical treatment under the conditions established by national laws and practices. A high level of human health protection shall be ensured in the definition and implementation of all the Union's policies and activities." Article 35, Charter Of Fundamental Rights Of The European Union

After Article 33 of L4368/2016 came into force in early 2016, free access to public health care in Greece became a granted right to everybody residing in the country: however, the reality of the past half a decade shows a structural weakness in the public sector to cope with this mandate - whether as regards Greek citizens in Greece or foreigners alike.

Obstacles to health care access for displaced communities in Greece became relevant already under the SYRIZA administration, when asylum seekers were faced with the arbitrariness of the administrative issuing of social security numbers (AMKA). This situation was nonetheless worsened on July 11th, 2019 - 3 days after Nea Dimokratia was sworn into government - with a circular by the Ministry of Labour which de facto stripped off the right for asylum seekers to apply for an AMKA. In the months that followed the circular was amended, but no new regulation came into place to counteract the administrative obstacles to asylum seekers' access to social security - a reality that, still to this day, even concerns children of third-country nationals born in Greece to parents ‘residing illegally in the country’. Without the issuance of an AMKA, refugees and asylum seekers are in addition more likely to be further hindered in terms of accessing other services such as employment and social security for example.

At times, the structural inequality of Greece social security and its systematic disregard for displaced people’s increased social vulnerability becomes more apparent, such as through the harsh impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent failure by national authorities to include residents of reception centres in the vaccination campaign, or during the devastating heatwave that hit Greece in late July 2021.

Going along with the year long lasting policy of segregation of third country nationals in regards to their participation in social welfare, it does not seem surprising at all that Athanasios Plevris – “lawyer and the son of Greece’s most influential fascist and neo-nazi Konstantinos Plevris” – took over in August 2021 as Minister of Health Care. His particular attitude towards people-on-the-move came further in the spotlight back in April 2011 when he said that “[t]here is no border protection without deaths”.

Adding to this statement, Plevris even threatened migrants by proudly saying: “When you’re here, there will be no social benefits, you won’t get anything to eat or drink, you won’t be able to go to the hospital, and you’ll be telling others in Pakistan, ‘We’re worse off here.”

Most recently, between September and December 2021, these injustices were further aggravated by the lack of food provision in reception facilities in Greece. While the quality of the food provided in these structures has always been extremely low, since at least October 2021, a stunning 60% of the people living in camps across the country did not receive any food. Although food seems like the most basic human need, the Greek government denies support to all recognised refugees and to the ones with negative decisions regarding their asylum claim.

This news came at a time when the management of the cash assistance program got handed over to the Greek government by the UNHCR. After the transition of this vital program for asylum seekers, the ministry communicated in mid-October, that the first transfers of money will be done at the end of the same month, stating that “[t]here are no problems with the transition.”

More than a month later the ministry communicated that the US-based charity “Catholic Relief Services” will take charge over the cash assistance program – awarding them with a total of 12,000,000 euros. The system is now supposedly working, despite many reported shortcomings such as for people who received a rejection during the four-month gap of cash assistance, who are now unregistered and excluded from monetary compensation.

Anecdotal recollection of such failures can only serve to showcase the structural nature of the institutional neglect to the human right of healthcare and basic needs provision in Greece. Even if this acknowledgment by itself would already be enough to raise sufficient concerns to the state of asylum seekers and refugees’ treatment in the country - one must not confuse the ‘tip of the iceberg’ for the deep, entrenched and eradicated system of marginalisation, discrimination, dispossession and destitution that non-EU citizens are faced with in their effort to seek asylum at the shores of Greece.

Locked up, sanctioned, neglected for the sole reason of seeking asylum

"Greece’s new asylum law—the International Protection Act (IPA), which took effect on 1 January 2020—further restricts asylum seekers’ freedom of movement by increasing authorities’ discretionary power to impose restrictions on them. In what can be considered de facto detention, newly arriving individuals are automatically subject to a “restriction of liberty” that bars them from leaving the RIC for the first five days even upon lodging an application for international protection. This period may be extended for up to another 25 days to allow for the completion of reception and identification procedures. According to the IPA, detention should only be “applied exceptionally, after an individual assessment and only as a measure of last resort.” In practice, however, authorities systematically continue the restrictions on freedom of movement without conducting individual assessments." Walling Off Welcome, 2021 report by Danish Refugee Council

Unfortunately, institutional neglect is not the only factor that burdens on displaced communities in Greece: it comes enshrined in an environment of systematic discrimination and abuse that, if anything, is let free to prosper in the contemptuous or even endorsing attitude of the ruling class and authorities.

In March 2021, in the midst of the second countrywide lockdown due to the Covid-19 outbreak an official report proudly published by the Hellenic Police, presented the amount of fines issued in Samos, Lesvos and Chios against breaching of public health measures. These figures speak for themselves: for a total of 1,767 fines issued to locals, the police accounted for a remarkable 7,266 sanctions against 'foreigners'. For the avoidance of doubt, it suffices to say that 'tourist foreigners' in that season were clearly a negligible minority in those three islands where the 'foreign population' included about 15,700 asylum seekers and refugees (UNHCR estimates).

A few months later, on 24th August 2021, the Hellenic Police was once again caught handing fines as high as 5,000 euros to people-on-the-move who had literally just landed on Chios island - under the pretext of violating the regulation that requires the show of a negative test upon arrival. Later on, after the eventual revoking of this unjustifiable act, a statement by the Hellenic Police claimed a '‘misinterpretation of the law' to justify the behaviour of its officers.

The arbitrary and vindictive use of financial sanctions imposed on asylum seekers and refugees is but one of the many examples of systematic xenophobia and racial profiling that people-on-the-move in Greece, face by the hands of the very authority which is mandated with their protection.

Similarly, in May 2021, the attempted penal framing of 27-year-old Mohamad H. from Somalia, – to 149 years in prison – does not come as a surprise. Nor does the charge against 23-year-old Nadir for his own son's death at sea, off the coast of Samos, in November 2020.

If the people on this boat would have been tourists from northern Europe, the competent authorities would have reacted in no time. However, they were displaced people seeking asylum and refuge, and clearly recognisable as such, and for this reason alone their rights were denied. Yet, instead of investigating into the Hellenic Coast Guard accountability for their delayed response, the authorities decided to take it out on a young man who had just lost his child in the sea.

These occurrences of mounting institutional hostility towards people-on-the-move are nothing but symptoms of the clear-cut policy that has long been designed and adopted high up among the decision-making process of the ruling government party. When those individuals who, in moments of terrible distress at sea, take action to steer the dinghy ashore and save other people's lives are charged for “illegal transportation of third-country nationals into Greek territory”, if not endangerment of lives and eventual manslaughter, then it is clear that the call is one and one alone: deterrence.

Fortress Greece: surveillance and deterrence instead of protection and integration

One further step into such use of ordinary institutional power is the widely known process of increased securitisation and surveillance, and associated discourse of ‘migration control’, that the Nea Dimokratia government has been promoting ever since taking power in July 2019.

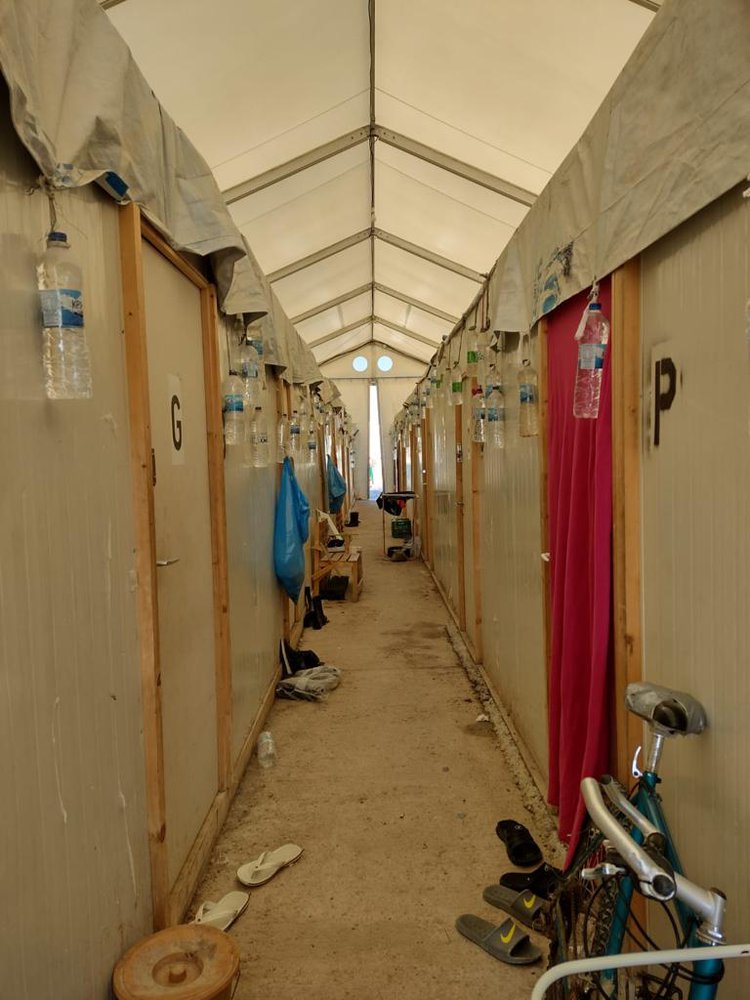

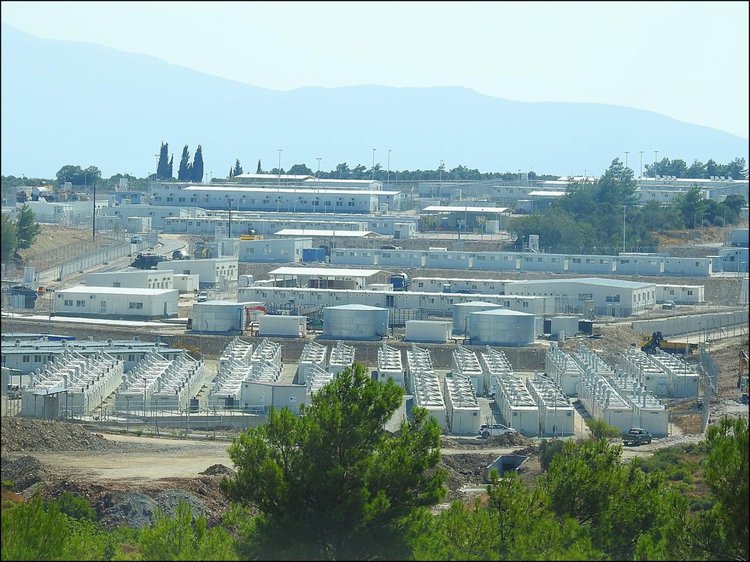

This approach translated, in early 2021, into the unjustified and utterly propagandistic setup of 3-meters high concrete walls around four ‘long-term accommodation sites’ in different locations in mainland Greece - a move that, at the very least, is designed to increase ‘the isolation and enforced separation between asylum seekers and the local community’. This is how, at present, thousands of people currently waiting for their asylum procedure are now literally segregated behind the walls of Ritsona and Malakasa camps, in Attika, and Nea Kavala and Diavata, in Northern Greece.

The same showcase is now visible not only on mainland Greece but also on the five ‘hotspot islands’, thanks to generous funding from the European Union. A total of 250 million € has been granted to finance the building of five superstructures on Lesvos, Leros, Kos, Chios and Samos.

The one in Samos is the first that started operating in September 2021 – marking a new chapter in EU migration policy. The aim of the overall project became even clearer in August, when General Secretary for the Reception of Asylum Seekers explained that the Ministry will invite businessmen to the new prison-like structure and declared: “We want [the displaced communities] to exist within the structure, so that there is no need to move in the city”.

The unwarranted show of power and control does not end in such haunting visions, but extends to a display of ‘technological mastery’, embodied by the newly integrated CENTAUR surveillance system. Presented as a part of the “National Migration Strategy 2020-2021, Protecting Aegean Island”, it is now first being used in the new “Closed and Controlled Access Center” on Samos since September 2021, and in Kos and Leros since December of the same year.

This CENTAUR surveillance consists of an “Integrated digital Electronic and Physical Security management system surrounding and inside the premises" including the use of "cameras and motion analysis algorithms (Artificial Intelligence Behavioral Analytics)" as well as systems of "central management from the Ministry headquarters”, in Athens.

It seems blatantly obvious that the aim of this new strategy is to monitor every single step of people placed in those new prison-like structures. These tight surveillance methods are not only taking place in Samos, since the overall aim of CENTAUR is to be able to connect to every single camera in the structures of the Aegean islands and other camps throughout Greece in the future.

As clearly stated by Migration & Technology Monitor researcher Petra Molnar, this all-encompassing surveillance system - comprising of "cameras, automated voice broadcasting, drones and also this kind of amorphous algorithmic detection analysis which no one can really know what exactly would entail' - does nothing but show 'that the priority of this project and perhaps for the Μinistry of Μigration is to normalize surveillance in these spaces."

Normalising abuse and unlawfulness - part 1: criminalisation of solidarity work

As testified by the promise enshrined in the 2019 electoral slogan - "the return to normalcy" - the government of Nea Dimokratia has kept busy since day one with multiple processes of normalisation. An endeavour, one should say, vowed to re-frame and re-define an arbitrary assumption of "normality" in the country, suspended after long years of "crisis".

Among these "normalities", is the one experienced by civil society groups working in the migration context, affected in practice by the shrinking of civil society space in the country. They have to deal with increasing pressure from a regime of intimidation and criminalisation which deploys a skilful set of administrative and legislative tools.

Charges and allegations of smuggling, abetting clandestine migration, corruption, money-laundering, exploitation – with little evidence to support the claims - seems to have become a daily obsession for a government that fails to appreciate the benefits of a multitude of organisations covering for the lamentable gaps in the provision of essential services and safeguarding of fundamental rights.

Particularly toxic and undermining is therefore the government’s dealing with the most “newsworthy” aspects of humanitarian intervention, that is the area of search and rescue (SAR). Only in September 2021, as pointed out by the Council of Europe, the so-called Bill on Deportations and Returns - eventually passed by a parliamentary majority of the ruling party - established and institutionalised “restrictions and conditions on NGOs active in areas of competence of the Greek Coast Guard, at the threat of heavy sanctions and fines”. The most direct and immediate effect of this new legislative frame, as suggested by the Council’s Commissioner for Human Rights Dunja Mijatović, “would seriously hinder the life-saving work carried out at sea by NGOs, and their human rights monitoring capacities in the Aegean”.

Once more, NGOs and solidarity groups are targeted and intimidated through a political use of legislative tools - giving the heavily compromised Hellenic Coast Guard a higher control power over the few independent watchdogs there to witness abuses of human rights at sea.

Nonetheless, this strategy of edging out civil society actors, in public propaganda and in administrative blockers, is coupled by the practical reality - out of the limelight - of systematically outsourcing the provision of services and assistance to the very humanitarian actors above targeted. It reveals a scheme and a vision that, at the very least, is one ready to play in the fine balance between narratives of "crisis" and of "control".

‘We are prepared to face a new crisis. We are clearly saying that we will not be Europe's gateway for illegal migration flows’ Migration Minister Notis Mitarachis in front of the Hellenic Parliament (06.09.2021)

Following this line, in December 2020, Minister of Migration and Asylum Notis Mitarachis took the opportunity to accuse once more "unnamed NGOs" of providing help to Somali migrants to reach the shores of Greece ‘illegally’. In the same statement Mitarachis claimed that these organisations covered the expenses of the travel to Turkey and the needed Visa to enter the country, before sending the people to smugglers in order to reach Europe.

Unfortunately, ungrounded accusations against human rights defenders are only one of the most visible features in this edging out process: just as impactful and detrimental is the introduction of an unintelligible nation-wide NGO register. While this record was already in the making under the previous administration, it became a literal bureaucratic nightmare under the Nea Dimokratia government that ever since its establishment is burdening on all organisations supporting people-on-the-move in Greece with lengthy requirements: nothing more than a Kafkian, time-consuming and expensive procedure – especially for small, understaffed grassroot NGOs with limited resources.

Once again, the whole establishment of this register responds, according to the Minister of Migration and Asylum, to the need of setting up "the same rules for all NGOs operating in Greece, to ensure that these organisations (or their members) are not linked to illegal activities whatsoever, as well as to verify that they offer high quality services to the beneficiaries" and supposedly, "the Register aspires to help the Ministry of Migration and Asylum to better coordinate the efforts of all the NGOs, to save human and material resources and, thus, to optimise the impact of their assistance, in the light also of their regular funding by EU or national budget".

Despite a facade of legalisms, as stated in the HumanRight360’s open letter to the Migration Ministry and European representatives, the National NGO Register "creates unnecessary and disproportional barriers on the work of NGOs and impedes freedom of association" for all organisations, including the medical actors that are often supporting the local Greek population as well. Similarly, in the words of the European Commissioner for Human Rights Dunja Mijatović, civil society groups are instrumental in protecting the rights of people-on-the-move and play a major role in reporting and documenting all sorts of human rights violations.

It seems rather evident that, in the urge to project an allure of “omnipresent control”, what gets in the way of the governments’ narrative is precisely the practical action and testimony of civil society groups - i.e. the very backbones of a thriving and healthy democracy.

Instead of relying on the beneficial availability of civil organisation’s solidarity to respond to the challenge of welcoming and supporting newcomers’ integration in Greek society, the Mitsotakis government has not only used up all tools available to criminalise the non-profit sector in Greece - but also worked to establish a far-fetched participatory civil society that is nothing but a dangerous charade to accommodate European observers.

In fact, the attempted defamation staged against human rights watchdogs Josoor, Aegean Boat Report, Mare Liberum - as well as the flimsy accusations moved against more than twenty humanitarian workers of the Emergency Response Centre International (ERCI) - all follow the same recognisable patterns, such as framing for espionage if not abetting illegal immigration and other forms of violations of immigration code. Briefly, civil society groups in Greece are threatened with the label of being nothing more than a “threat for the national security”, if not a refined and picturesque “Turkish Trojan Horse”. Again, for the sole reason of doing the work that every democratic system would expect of them.

On the other hand, the same "shaming campaign" seems to have been avoided when it comes to a selected group of organisations, nominally engaged in humanitarian work but the activities of which, upon further inspection, in the past years have raised more than just "someone's eyebrows".

An organisation that seems to enjoy peculiar favour among the current government is EuroRelief: a registered Greek evangelical NGO, founded back in 2005 and known for the strong ties between its parent foundation, Hellenic Ministries, and the conservative religious class in Greece.

Operating as one of the biggest aid groups in the old Moria camp – and currently in Mavrovouni – the EuroRelief staff has been subject to multiple complaints, addressed for example to the systematic practices on distributing bibles and attempting to instrumentalise provision of services to convert Muslim refugees. Adding on to this worrying behaviour, and what has brought many observers to question their impartiality - or the real interest that leads their "humanitarian action" – is the documented close connivance between this organisation and the Greek ruling party. Not to mention the real interest behind the government's favour - which seems directly proportional to how much control can be exerted on the organisation.

And the same sort of questions concern the work of another organisation, going by the name of Hopeten – formerly known as Hopeland. According to their website, Hopeten is part of the ESTIA II – a housing programme for asylum seekers and refugees, previously administered by the UNHCR and since the beginning of 2021 managed by the Greek Ministry of Migration and Asylum.

As such, Hopeten is supposedly working as a direct partner to the Greek government in providing accommodation to people-on-the-move in Athens. However, as revealed in an extensive report by Athens-based investigative newsroom SolomonMAG, Hopeten (or Hopeland) does not display any record of previous service or experience in the migratory context: founded as late as September 22 2020, Hopeland quite literally "borrowed" its mandate and functions from a (long-time inactive) charitable project managed by the municipality of Athens. Again, with close links to the current ruling party, Nea Dimokratia.

The list of uncanny irregularities that this organisation can allow itself while also enjoying a smooth and streamlined bureaucratic progression is quite remarkable, to say the least. After having been awarded an initial funding for 568.612,05 euros - despite submitting an application to participate in the ESTIA II program just one week before the deadline and issuing the first payment before even accessing the National NGO Register - Hopeten was then granted a further 5.3 million for the upcoming year.

By framing and targeting on countless occasions civil society groups across Greece, the Greek government intends to turn humanitarian work into a bureaucratic nightmare or a legally compromising endeavour, while diffusing a climate of mistrust towards those NGOs that actively engage in solidarity with people-on-the-move.

Given that it is quite clear who is benefiting from this impossible humanitarian context, the sole question that remains to answer is: who is paying the price?

“I listened with great concern to the defenders’ accounts of intimidation, threats and physical attacks by right-wing groups, as well as what appear to amount to smear campaigns against defenders in the media, allegedly instigated by MPs and police and involving the leaking of the defenders’ personal information, increasing their level of risk” Mary Lawlor, UNSP on the situation of human rights defenders (5.10.2021)

Normalising abuse and unlawfulness - part 2: legitimisation of violent border regimes

"The message is clear to everyone: do not try to enter Greece illegally, you won’t succeed, and you take full responsibility for your choices" Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis (03.03.2020)

In February 2020, the Turkish government opened its side of the Greek-Turkey border as a response to the lack of international support the country has received to support over 3 million refugees - demonstrating again how refugees are used as a form of political brinkmanship. Greece responded by adopting even more aggressive border control measures, increased bio-political surveillance of its border and termination of its asylum service for a month – plainly violating Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

Using tear gas, water cannons, plastic bullets and live ammunition, the increasingly aggressive behaviour by Greek officials ultimately cost the lives of two asylum seekers on the 22th respectively 4th March 2020 – shot dead at the border.

However, the Greek authorities are not the only ones taking a step back from the rule of law. While the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, Frontex, was present at Evros back in March 2020, its presence itself was not in line with Article 46 of the Regulation (EU) 2019/1896, which states that the executive director has to “withdraw the financing for any activity by the Agency, or suspend or terminate any activity by the Agency, in whole or in part, if he or she considers that there are violations of fundamental rights or international protection obligations related to the activity concerned that are of a serious nature or are likely to persist.”

Having already withdrawn from all activities in Hungary in January 2021 as a result of rights abuses, it seems dubious that the highest funded EU agency is still allowed to operate in Greece, where similar concerns have been raised over the past years.

Recent research shed even more light on the highly illegal practices happening in Greece, while this time focusing on the Aegean Sea. In a joint effort, several media outlets conducted an 8-month investigation into the so-called ‘shadow armies’ across Europe’s external borders. This second big investigation on border violence in the Aegean within a year, was able to identify the ‘masked commandos’. In this thorough examination they found out the obvious: these men wearing balaclavas during pushbacks are part of the special forces of the Hellenic Coast Guard.

Extensive documentation shows that the aggressive forms of border violence called "pushbacks" involve all sorts of psychological abuses, verbal and physical harassment, theft of personal property, forceful undressing, brutal beatings, and a general mistreatment and disregard for the human dignity of people-on-the-move. Other than the blatant fact of ignoring international and national law, which mandate that the right to seek asylum must be respected regardless of the method of entry in national territory.

One of the countless examples of illegal refoulements happening in the Aegean is the case of Junior Amba and his pregnant wife. Having reached Samos in April 2021, masked men found them hiding in a hill area alongside 26 other asylum seekers and forced them on a dinghy without engine and life jackets – floating towards Turkey until they were eventually rescued hours later by the Turkish Coast Guard. Their case is not an isolated one – pushbacks are happening on a daily basis.

Naturally, after being faced with the allegations, the Greek Migration Minister claimed that “Greek borders are EU borders and we operate within international and European law to protect them”.

Another striking example of institutional ignorance regarding the circumstances and reasons to flee a country has been shown in the light of the Taliban take-over in Afghanistan in August 2021. It was once more Mr. Mitarachis, reacting to the developments and stating “We cannot have millions of people leaving Afghanistan and coming to the European Union [...] and certainly not through Greece.”

Reflecting the common goal of the European border regime to prevent a ‘repeat of 2015’, Greece proudly announced that the extension of its 40 km long border wall had been completed successfully after the Taliban’s takeover. The systematic character of such regimes of border violence was aptly described by researcher Özgün Topak: "In these liminal spaces, sovereign border practices reign supreme over human rights and refugees and migrants are abandoned to death".

Similarly, the nonsensical conceits by which "national security" is brought about as an excuse for violent abuse over displaced persons has also been the subject of uncountable protests, voicing out the frustration of Greek and European citizens who witness national authorities literally priding themselves of enforcing a "border security" that is nothing more than a inhumane "hunt on refugees”.

As brilliantly summarised by Bodo Weber in the wake of Mitsotakis' maneuvers to "seal" the Evros border and realise Greece destiny as "the shield of Europe" in March 2020, "the phrase "protection of the external border" of the EU is entirely misleading, as it suggests the establishment of law and order, while it in fact means illegally preventing refugees and asylum seekers from entering EU territory”.

In the light of increasingly more pressing evidence of the systematic nature of these violent border regimes across all over Europe, a first step against these inhumane actions would be a real compliance monitoring of the Geneva Convention: despite all EU members having signed the 1951 convention and its protocols, it is clear that a lack of accountability translates into nothing but a violation/eroision of EU fundamental values.

Closing remarks: Crafting ‘irregularity’ to legitimise security discourse

On the first anniversary of the fire that burned down the infamous Moria camp, the very chief of Frontex, Fabrice Leggeri was arguing that “2015 was a trauma because as a result 1.2 million people illegally crossed the external border. Shortly afterwards there were several attacks in Europe. The lack of control showed that the EU is weak. That is why a lot has been done in border management, surveillance and security” (interviewed with Welt, September 9th, 2021).

After insinuating that the 2015 migratory movement was to be linked with the violent attacks in continental Europe, Mr Leggeri then went on to seemingly defend the national authorities' prerogatives to push people back at sea, claiming that the right to asylum would supposedly be admissible only when people cross at 'official' border crossing points.

These sorts of statements, riddled with very problematic implications, ultimately manifest the one populist conceit that informs all nationalist and securitarian regimes' narrative: that migration inherently constitutes an existential threat to the heart of a nation and to the safety of its citizens. In other words, the transnational movement that displaced people embody in the very act of crossing a border outside of 'official entry points' brings into question the reality and concreteness of the border itself - and this is perceived as nothing less than a slap in the face on everything that frontiers, flags, documents stand for.

Such a narrative framing becomes even more evident when considering the forcible 'irregularisation' - and subsequent criminalisation - that the displaced persons are suffering from arbitrary criteria that have nothing to do with how they crossed the border into Europe. Evidently, with the absence of a legal pathway to apply for asylum ‘regularly’, people-on-the-move have no other choice than taking dangerous journeys in order to apply for asylum. Another staggering fact about people being forced to take these passages is that their irregularity is purely based on their heritage – nationality and country of origin.

The political vulgarisation of common knowledge on asylum procedures reached a new low on the 27th October 2021, when Minister Mitarachis – in the light of a shipwreck off Chios island where at least 4 people died – claimed that the majority of them were from Somalia, Sudan and Eritrea, and that they were therefore not in danger in Turkey: “they were not refugees who left Turkey to be saved. The information we have is that they were not wearing life jackets.”

As was mentioned, the labelling Turkey as a “safe country” for top-down designated nationalities of refugees as a “one-size-fit-all” criteria is just a further step into the systematic circumvention of the international asylum law. Apparently, the political discourse in Greece and Europe is largely forgetful of the unquestionable fact that it is the very EU migration policies that are “crafting and manufacturing” so-called “refugee crisis”.

People-on-the-move from Sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa and the Middle East can be arbitrarily portrayed as an ‘invasion’, while on the other hand European countries can welcome approximately 3 million Ukrainians without ever making this fact an issue of “national security”.

This acknowledgement not only reveals that dynamics of systematic exclusion, isolation, discrimination and deterrence in Europe are always informed by racist and colonialist paradigms. It also shows that European policy in regards of Schengen visa and migration reception is dependent on national governments’ agenda as regards the management of incoming migration in their own sovereign territories. Giorgos Tsiakalos plainly explains in an interview with SolomonMAG that:

under pressure from Poland, the EU, in May 2017 tackled the problem of irregular migration by removing Ukraine from the list of countries requiring Schengen visas” and this is how “the “irregulars” or “illegal immigrants” as they would be called by some in our country, became legal overnight and are no longer a threat, they can travel freely to any EU country [...] If the same was true for Afghans or for citizens of any other country, who seek to enter Europe illegally via Greece, then they too would be able to freely travel to any EU country, and that country would decide whether it would allow them to stay or not. [...] However, while Greece agreed that Ukrainians were no longer a threat to Europe and made it easier for Poland, Greece did not make the same request of citizens passing through our country. Greece didn’t even veto or raise the issue, but most of all Greece didn’t ask for anything in return. For example, Greece could have agreed only if the EU would accept the free movement of people who are granted asylum in Greece. But Greece did not do this. [...] The EU makes enemies on paper and, whenever they want, during one session they turn enemies into friends, and keep others on the list of dangerous and unwanted. From there on, the EU behaves accordingly towards that group of people.

At the same time, and just very recently, the ‘Riace Model’ in Italy has shown an example of migrants’ reception based on those very values, of political accountability and civic solidarity, and how this compliance can produce beneficial solutions not only for the individuals directly affected but also for the local context and the region as a whole. The sentencing of the leader and creator of the ‘Riace Model’, Mimmo Lucano, to 13 years of prison sends an unequivocal message: the undermining of welcoming and compassion is now institutional.

Ultimately, Greece’s illegal government and its accomplices across Europe are doing all that is in their power to further marginalise the marginalised, to further isolate the isolated, to make the irregulars even more irregular.

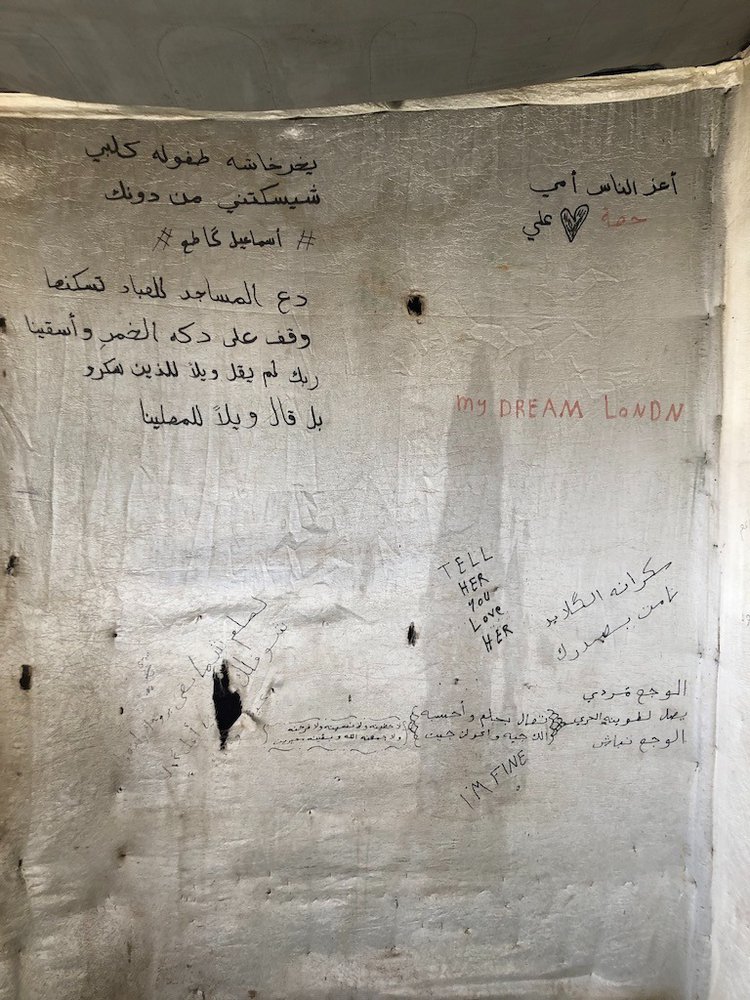

We can see that across the streets of Athens and Thessaloniki, where families of refugees are forced into homelessness by the closing of housing projects and cash assistance. We see it around the small municipalities where grey, 3-meters high, concrete walls are erected around ‘long-term accommodation sites. We see it in the Aegean, where local communities see their islands turned into ‘floating prisons’ before their own eyes.

Thus, the Greek government is systematically sowing the seeds of radicalisation and discord, instilling prejudice and misinformation, fuelling vindictiveness, resentment and violence.

It is utterly clear that this government scarcely cherishes the future of Greece. If that were the case, Prime Minister Mitsotakis, his cabinet and the ruling party would show at least a hint of interest for long-term payoffs in terms of political, economic, social stability of the country — instead of jeopardising the present and future of not just the thousands of people seeking asylum in Greece, but also of the millions of Greek citizens that have no saying in the policies decided upon their lives.

Instead, we see the capitalising on populist consensus on a short-term perspective - and it is leading the country towards a social crisis.