Mediterranean

Published November 15th, 2021 - written by: Christian Jakob

written in October 2020 and last updated in November 2021

Current Situation

If you want to know about the extent of the daily, avoidable deaths of migrants on the Mediterranean Sea, the best place to find out is the Alarm Phone initiative reports. Since 2013, this project has been trying to organize help for people in distress at sea between Africa and Europe. Well over 100,000 people have been in distress in boats that have made contact with the Alarm Phone volunteers. This, as an example, is a snapshot of their work in one single week in September 2020. And since then, the situation has not changed:

- On 18 September, at least 20 people went missing and are feared to have died following a shipwreck off Zawiya.

- On the same day, fishermen rescued 51 out of 54 people in two separate interventions, but they arrived too late for at least three people who died off Garabulli.

- On 19 September, a fisherman rescued more than 100 people off Zuwara, but upon their arrival on land, two people jumped from the pier to escape arrest and died.

- On 21 September, the deadliest shipwreck recorded until this article was published killed more than 110 people. Only 9 people were eventually rescued by a fisherman.

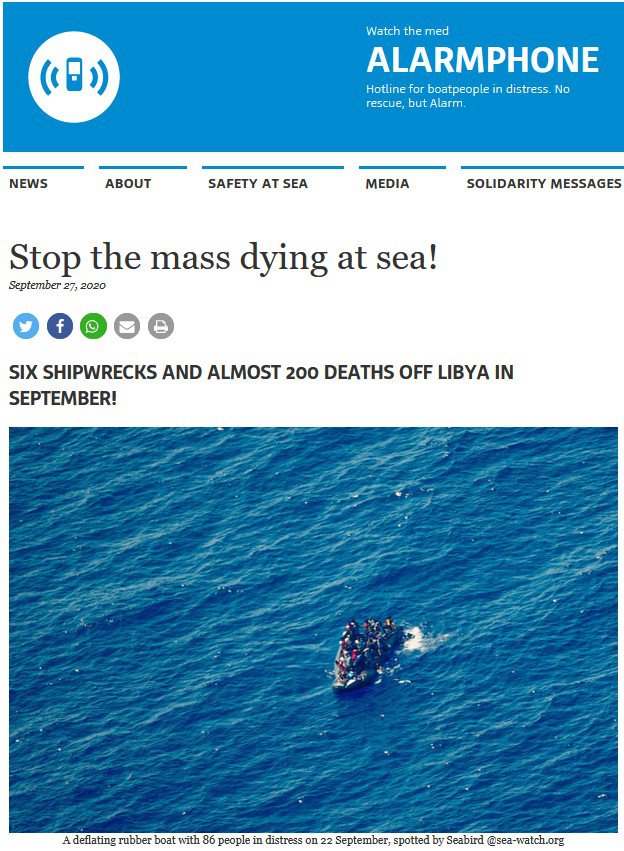

- On 22 September, people in distress who reached out to Alarm Phone reported that 4 people had jumped or fallen into the water, and their fate is still unclear. Seabird spotted several people in the water just before interception by the so-called Libyan Coast Guard. Their fate is unclear and we fear the worst.

- On 25 September, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) reported another shipwreck where 16 people lost their lives.

- On the same day, a boat in distress reached out to Alarm Phone and reported that at least two people on board had died – Seabird spotted the case the next day and reported 3 deaths. A day later, on 26. September, IOM reported that survivors testified to 15 deaths in this case.

How is this possible?

Things have been going on like this for years in the Central Med. And for years, civil society organizations had drawn attention to these dramas. The Amsterdam NGO United for Intercultural Action collected reports about a total of 44,764 people who died trying to enter Fortress Europe from 1993 until June 2020.

This was why 2015 saw the emergence of a whole new type of private NGOs for sea rescue which did what the state institutions refused to do: assist migrants at sea when they needed it. There were times when up to 12 organizations with their own ships were on site, saving tens of thousands of lives. But starting in 2017, the authorities took increasingly repressive action against them – with offensive criminalization and flimsy regulations. The intended consequence was, that there were repeatedly phases in which not a single rescue ship was on site while more and more people drowned. At the same time, the NGOs had to collect more and more donations in order to acquire new ships – the old ones had been partly confiscated by the authorities.

In the meantime, supported by the EU, the Libyan government of Fayiz as-Sarradsch has registered its own rescue zone. Since 2016, the so-called Libyan coast guard trained and equipped by the EU, has been stopping migrants at sea and bringing them back to torture and detention. Since the beginning of this cooperation, Libya's coast guard intercepted more than 95,000 people and locked them up in camps (2021 (January to 19 November): 29,427; 2020: 11,265; 2019: 9,030; 2018: 14,950; 2017: 15,350; 2016: 14,300).

In 2015, the EU had launched a military mission called EUNAVFOR MED/Sophia in order to take action against the smugglers in Libya. Initially, information about them was to be collected, for example by drones. The EU always tried to portray the mission as a „rescue operation“, although this was not the primary task. Since April 2019, the mission has been limited to training the so-called Libyan coast guard. In 2020 it was decided not to restart it – Austria and Italy rejected a restart. Greece and Hungary had also shown reservations. A unanimous decision would have been necessary to revive „Sophia“. The reason was that the EU states could not agree on a system for distributing rescued persons. From January 2016 to June 2018, according to a census by the International Organization for Migration, the „Sophia“ ships were involved in the rescue of 35,200 people, which was about one tenth of the total number of rescues in the central Mediterranean during this period. If a new start had been made, the reception and distribution of refugees would also have had to be clarified. Eastern European countries in particular categorically rejected both. Instead, a new mission called „Irini“ was launched in mid-2020, which was merely to monitor compliance with the arms embargo. For this purpose, it patrols far outside the areas where most migrant boats are in distress.

Nevertheless, the EU is continuing its air surveillance of the region. In doing so, it has been involved in pushing back tens of thousands of refugees and migrants in the Mediterranean in recent years. European Border and Coast Guard Agency's (Frontex) airplanes track down refugee boats and direct the so-called Libyan coast guard to them. „Actors of the EU have thus become accomplices of serious human rights violations", states a report presented by the initiatives Alarm Phone, Sea-Watch, Borderline Europe and Mediterranea. This is a „widespread pattern“ of behavior by EU authorities, who have a „crucial role“ in locating boats and coordinating remote interception. Accordingly, the EU bears clear responsibility for the forced return of migrants to Libya.

The roots of EU's border control beyond southern Europe

After Spain closed the western Mediterranean route, from 2005 onwards, increasing numbers of refugees arrived mainly in Malta and Italy, as well as Greece. The clique around the, at that time, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi and his two right-wing coalition partners, Gianfranco Fini, then head of the post-fascist National Alliance (Alleanza Nazionale), and Umberto Bossi of the separatist Lega Nord, who had ruled Italy since 2001, took a hardline stance. In 2003, Bossi called for the use of cannons against ‘illegal immigrants’: “After the second or third warning – boom. Without any more talk, the cannon fires. The cannon kills. Otherwise, we’ll never see the end of this.” Later, in an interview with the renowned Milanese daily Corriere della Sera, Bossi claimed it was just a “joke.”

It was clearly no laughing matter when the Italian government took Tunisian fishermen such as Abdel Basset Zenzeri to court for bringing 44 shipwrecked migrants to Italy.[1] For the same reason, Italy seized the ship of the German aid organization Cap Anamur in 2004. Italy then showed no intention of rescuing shipwrecked refugees.[2] They often drifted at sea for days on end. Many died of thirst instead of drowning. Tineke Strik, a Dutch professor of migration law and nowadays member of the European Parliament, has investigated for the Council of Europe (CoE) why NATO and the EU watched 61 refugees drift for two weeks on the heavily monitored Mediterranean Sea in March 2011. In the end, 50 of them were dead. “Nobody helped them,” says Strik.[3]

Nobody was counting the dead, either. Unlike today, with statistics provided by IOM, in the past decade no one kept official statistics, even though thousands were dying. The only people who felt responsible were volunteers. A group led by Italian journalist Gabriele del Grande of Lucca spent years painstakingly analyzing newspaper reports from around the Mediterranean. Their blog ‘Fortress Europe’ strives to document the scope of the tragedy. At the same time, the Amsterdam NGO United for Intercultural Action collected reports about a total of 34,361 people who died trying to enter Fortress Europe from 1993 until mid-2018. Had it not been for the volunteer efforts of both groups, the death toll at Europe’s gates would never have been recorded.

Since 2003, a fundamental imbalance in Europe’s asylum law has determined the situation in Italy: Regulation 343/2003, commonly known as Dublin II, in force since 1 March 2003. It essentially states that the country through which refugees enter the EU is responsible for them. If refugees or migrants go to another EU country nevertheless, they will be deported back. This is obviously unfair not only towards the refugees, but also towards the states at the EU’s external borders. Ever since arrivals began to rise around 2003, the government in Rome has been calling for compensation, without success. After 2010, the asylum system collapsed, primarily in Greece, Malta and Italy, which had disastrous consequences for the reception of refugees. But countries such as Germany stuck to the procedure anyhow. “Dublin II remains unchanged, of course,” declared Hans-Peter Friedrich (CSU), the at that time German Federal Minister of the Interior, in 2013. He stated that critics had "lack of expertise". In the meanwhile, the Dublin III regulation was adopted, but remains similar to Dublin II.

Since the 1990s, an estimated 20,000 refugees had already died in the Mediterranean, when an especially grim catastrophe strikes on 3 October 2013. Over 360 people, most from Eritrea, drown within sight of the island of Lampedusa when their boat catches fire. Not all of the bodies can be recovered. The disaster is a turning point in the debate. A few days later, 280 dark wooden coffins, each bearing a long-stemmed red rose, are displayed in a corrugated metal hangar near the port of Lampedusa. “I will never forget the sight of 280 coffins today. I will bear this with me for the rest of my life,” says the at that time EU Commissioner for Home Affairs Cecilia Malmström. “This isn’t the European Union we want.” Malmström visits the Mediterranean island together with the then President of the European Commission José Barroso. Hours after the photo session in front of the coffins, Malmström announces the creation of a “task force.”

Public opinion also changed in Italy. In February 2013, Enrico Letta (Partito Democratico, PD) becomes prime minister. Letta orders a national day of mourning for the deaths near Lampedusa – the first time ever for dead refugees. On 18 October 2013, he launches the naval mission Mare Nostrum (Our Sea) under Admiral Guido Rando’s leadership to rescue shipwrecked people and escort refugee boats to the mainland. An entire naval unit is deployed close to Libyan territorial waters. Within a year, navy personnel rescue some 150,000 people, more than ever before. At the same time, 3,165 people drown in the central Mediterranean. Without Mare Nostrum, the toll probably would have been much higher. “We applaud,” says the International Organization for Migration (IOM), and “pay tribute to the heroic work of Italy’s maritime forces.”

Applause came, but money did not. The EU pays only about one-sixth of the monthly expenditures of about $12.2 million. Italy is not just left to pay the remainder; according to the Dublin Regulation, it also is solely responsible for all the rescued migrants. In February 2014, Matteo Renzi (PD) becomes prime minister of Italy. His plea for a fair distribution of the burden falls on deaf ears. To build some pressure, Renzi orders Mare Nostrum units to pull back a bit from the Libyan coast. The death toll skyrockets: from January to April 2014, 60 deaths had been recorded; in the months following the retreat, there are between 314 and 839. The fatal demonstration leaves Europe unimpressed. Unlike the 2013 disaster, people are now dying slowly, one by one, not all at once. Hence the media pays little attention.

The EU does not want to pay for Mare Nostrum – it wants to end the mission. “Mare Nostrum was meant as emergency aid and has turned out to be a bridge to Europe,” says the at that time German Minister of the Interior Thomas de Maizière. In the first nine months of 2014, the number of new asylum seekers in Germany rose by almost 60 percent to around 116,000. Many domestic politicians saw this as a result of Italy’s rescue policy.

The EU border protection agency Frontex also views Mare Nostrum as a “pull factor,” an invitation to refugees in Libya to embark, because they would not need to get far before they had a chance of rescue. Research shows that this is not the case: “A closer look at what is happening in the Mediterranean shows that it is unfounded to present the presence of sea rescue boats as the primary reason to migrate”, writes Global Public Policy Institute's Niklas Balbon in his meta-analysis on various investigations on the "pull-factor"-theory for Libya. If this prospect no longer existed, then “considerably fewer migrants” would risk a departure, states Frontex in leaked meeting minutes from this period. The EU agency wants to halt the Italian navy operation and the monitoring of Libyan territorial waters. Instead, Frontex wants to launch its own “Triton” mission to guard only Italy’s coastal waters.

Frontex knows what this would mean. In a concept paper written in August 2014, the agency warns that it was “likely” that the withdrawal of Italy’s navy would increase the death toll. “The priority for the EU and Frontex is clearly deterrence. That took precedence over human life,” says Lorenzo Pezzani, a researcher at Goldsmiths’ College, London. The EU decision-makers were “aware of the risk in detail.”

On 3 September 2014, the EU Parliament’s Committee on Civil Liberties and Internal Affairs invites Frontex Executive Director Gil Arias-Fernández to a hearing. MEP Barbara Spinelli asks him if he was “aware that more people will be dying again in the Mediterranean,” if Mare Nostrum is discontinued. Arias-Fernández simply replies that the Triton mission will not replace Mare Nostrum, neither its mandate nor its available resources.

Nevertheless, Mare Nostrum is officially phased out on 31 October 2014 and Operation Triton takes its place. Italy remains uneasy about this decision: Initially, Rome still lets some of its ships cruise near Libya for rescue operations. Frontex tries to prevent this. Klaus Rösler, head of the Frontex Operations Division, writes a letter to Giovanni Pinto, director of the Italian border police. Rösler criticizes Italy for continuing to respond to emergency calls outside the 30-mile zone. This was not in line with the operative plan, he warned.

Two weeks after another serious ship accident on 23 April 2015, EU Commission President Juncker addressed the EU Parliament: “It was a serious mistake to bring the Mare Nostrum operation to an end. It cost human lives.” He increases the budget for Triton to $135 million a year, which was exactly what Mare Nostrum had cost. This was intended as a “return to normality. It was not right to leave the financing of the Mare Nostrum operation to Italy alone.” But the mistake cannot be undone. For years, the EU will not be able to build the rescue capacities to replace Mare Nostrum.

Germany and a few other states sent naval units. The EU extends Triton’s area of operations: Instead of 30 miles, the ships now patrol up to 138 nautical miles south of Italy – but still a long way from Libya. This is the critical difference to the Italians’ previous activities. They had sailed close to the Libyan coast, since most of the accidents happened there. The EU, on the other hand, now follows the Frontex dictum that a strong rescue force near Libya “triggers emigration,” as Rösler later puts it.

In the ensuing years, the number of deaths keeps rising: From January 2015 to February 2019, at least 12,046 people drown off the Libyan coast. This far exceeds the death toll from some African civil wars.

The reaction of Civil Society

Not everyone is willing to just let this happen. What follows is the finest hour of Europe’s civil society. More than a dozen private NGOs appear on the scene. Organizations of a type which never existed before.

The NGOs are backed by people like Marcella Barocco of Nijmegen, Netherlands. On 10 April 2015 she begins her shift: eight hours staffing the Alarm Phone hotline for refugees in distress at sea. The NGO has no office; Barocco works from home, just like some 80 other activists. “Our aim is to help to change things in real terms,” she says.

Since October 2014, volunteers from Europe, Tunisia and Morocco have been running the project: every day, around the clock. Some of the activists came to Europe as boat people themselves. They spread the hotline number through the Internet, refugee organizations, migrant communities and social media. The idea is that refugees who get into trouble should first make an emergency call and then inform the Alarm Phone initiative.

Alarm Phone, which is funded by donations, went into action on 11 October 2014. This was the first anniversary of a terrible accident: In 2013, more than 260 Syrians drowned off Lampedusa as Italian and Maltese coast guards argued back and forth who should be responsible. This was the first time that German, Italian and Swiss activists documented in such detail how organized irresponsibility leads to the death of hundreds of refugees at sea. “We want to make sure that this won’t happen anymore,” says Barocco.

They found the Alarm Phone, create a detailed manual and train volunteers. The first thing is to tell callers that they are not connected to a rescue service. And then to ask for as much information as possible, as quickly as possible: the callers’ position, size of the boats, size of the group, are there any sick people, are there any pregnant women, is the engine still running, is water leaking into the hull?

From October 2014 to October 2021, Alarm Phone volunteers receive emergency calls like these from around 4,000 boats with a total of way over 100,000 passengers: an average of more than two emergency calls per day.

At the start of the project, the activists wrote a letter to the rescue control centers. “We announced what our role would be, that we see it as our duty to build up pressure, if we feel that a rescue is not undertaken immediately,” says Barocco’s fellow volunteer Maurice Stierl. This “may be somewhat unwelcome,” but rescue services would have to learn to cope with it. In fact, activists were convinced that rescue services were “not always doing everything” possible. At the moment, said Stierl in May 2015, this has improved: “Right now there is a great willingness among the Italian rescue services, but there is far too little rescue capacity, and that is a political decision.”

Official rescue capacities fall short, but others step in to help: people like Harald Höppner. On 19 May 2015, the small business owner from the German state of Brandenburg registers the nonprofit association Sea-Watch under the number VR 34179 B at the district court in Berlin-Charlottenburg. Three weeks later, a converted fishing cutter that Höppner bought for $112,000 leaves from Hamburg to Malta. On the boat, which is also named “Sea Watch,” a crew of volunteers aims to keep an eye out for refugees on the Mediterranean and help them. They carry drinking water and life rafts for up to 500 people. The ship is not meant to take on refugees, but to alert the coast guard in emergencies. A “complicated undertaking,” says Höppner. But “doing nothing is not an option for us.”

Many people share his attitude and follow Höppner’s example: By 2020, the NGOs Doctors Without Borders and Save the Children (both international), SOS Méditerranée, Jugend Rettet, LifeBoat, Mission Lifeline, Sea-Eye, CivilFleet, Mare Liberum, United4Rescue/#WirSchickenEinSchiff (all based in Germany), Migrant Offshore Aid Station (Malta), Proactiva Open Arms, Salvamento Marítimo Humanitario (Spain), Stichting Bootvluchteling (Netherlands), Mediterranea and Mayday Terraneo (Italy) have sent rescue or monitoring boats to the Mediterranean – all are funded by donations.

Their goal is to rescue the living and recover the dead. Where the EU states fail to meet the need, alternative communities emerge to rescue shipwrecked people. They buy ships and drones and lease planes. Growing numbers of volunteers join them to meet the boats full of refugees and distribute life jackets, pint bottles of water and emergency blankets. These volunteer groups shoulder state tasks, but unlike official welfare organizations, they get no state funding, because their work undermines state policies. They do not just reject these policies; they resist by fulfilling their own demands. Although they first stepped up in response to an emergency, in time they build solid professional structures, adapt to circumstances and seek pragmatic solutions. They change state institutions. And they change themselves.

For a long time, refugee groups held all authorities equally responsible for the high death toll. Yet, since forming working relationships with state rescue organizations through their activities, some refugee activists are now more discerning. The Italian Sea rescue center in Rome, MRCC, also dropped its initial mistrust. Since spring 2016, the MRCC has been inviting private sea rescuers to regular meetings.

The sea rescue community hopes to become redundant at some point, hoping the navy and coast guard will eventually start doing their job again.

Ferries not Frontex, demands Sea-Watch, safe and legal routes to Europe. Nobody should be forced onto the smuggler boats; nobody should need to be pulled from the water by volunteers or Italian navy forces. Above all, sea rescue NGOs want to draw attention to the ongoing catastrophe at the fringes of Europe. Their activists seek to break through the indifference and the numbing of public empathy: if need be, with the photo of the dead baby recovered by Sea-Watch on 27 May 2016. The NGO shared the image with news agencies to show the world, once again, the fate of one in 23 refugees trying to reach Europe via Libya at that time.

The Libya situation

While Harald Höppner of Brandenburg was buying his first ship and thus catalyzing the growth of a whole generation of new NGOs, the EU was increasingly looking to Libya. To Europe, the country is the key to gaining control over irregular migration. Almost all migrants who come to Italy by sea set out from Libya. But since the fall of Gaddafi in 2011, turmoil has spread throughout the country. Can a state like this be a partner?

In May 2015, EU Foreign Affairs Commissioner Mogherini travels to the UN Security Council in New York. She wants a mandate to use military force against the smugglers. The EU is considering using combat helicopters to destroy smuggler boats along or off the Libyan coast, before they take refugees on board. This proposal has no precedent. Multiple groups and militias are vying for power in the oil-rich state, which is dominated by tribal structures. The interim Government of National Accord (GNA) around Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj has been internationally recognized in 2015.

In June 2015, a month after Mogherini’s trip to New York, the EU must accept that a military operation is out of the question for now. The UN has given a mandate only for “phase one” of the operation: reconnaissance on smugglers. “We view every landing attempt in Libya as an attack,” says Khalifa Ghwell, prime minister of the Islamist Fajr Libya (Libya Dawn) rebel government. “After all, we haven’t even been consulted about the plan.”

Hence, the EU navy mission EUNAVFOR MED starts off without teeth in June 2015. “The target is not the migrants. The target is those who make money with their lives and, far too often, with their deaths,” Mogherini explains. The Italian aircraft carrier Cavour leads the operation, which includes five ships, two submarines and drones, three aircraft and three helicopters. 1,000 soldiers are deployed.

But almost nothing happens. Despite its diplomatic efforts, the EU is unable to quell the chaos in Libya. It does not even dare to open an embassy for security reasons. And the EUNAVFOR MED soldiers are not allowed to approach the Libyan coast. So, the smugglers go on about their business.

The EU interior ministers meet on 13 October 2016. German Minister of the Interior Thomas de Maizière demands once more that refugees rescued in the Mediterranean be returned to North Africa. He says that asylum claims should be examined while the seekers wait there, in “safe accommodations.” His Austrian colleague, Wolfgang Sobotka, wants “an agreement by which Europe can send refugees back to Libya immediately.” Hungary wants similar conditions. But the EU is still divided on the Libya option.

Phase two of the navy mission begins on 24 October 2016. EUNAVFOR MED is now renamed Operation SOPHIA, after a baby born on the German frigate Schleswig-Holstein. A Dutch and an Italian training ship leave the port of Catania in Sicily. For months, the EU has searched Libya for participants to join its upcoming training measure. Candidates must have served two years in the Libyan Coast Guard, commit for another two years, and be loyal to Prime Minister al-Sarraj’s government. A security check is supposed to prevent jihadists from joining.

On 26 October 2016, 89 selected Libyan coast guards board the vessels for an 84-hour cram session: the course schedule includes human rights, maritime law, maritime safety, marine conservation, sea rescue, fishery monitoring and English, a full twelve hours per subject. The instructors come from Belgium, Greece, Germany and the Netherlands. The UNHCR and Frontex are also sending experts.

Some of the coast guards still came from the Gaddafi era, says SOPHIA commander Manlio Scopigno. They were “well organized, eager to learn and teachable.” However, they had “no knowledge of human rights or maritime law” and were “not at the standard of Western coast guards.” They stood out for their “very aggressive demeanor,” says Scopigno. Hence, the goal of the training course was “less aggressive behavior.” The EU has trained a total of 237 Libyan Coast Guard members as of 2018.

The Libyans are supposed to catch the smugglers, while sending refugees back to Libya is still a taboo subject at this time.

In early February 2017, an internal situation report becomes public. It was written by the German embassy in Niger’s capital Niamey and deals with conditions in Libyan prisons, where smugglers detain migrants who intended to leave the country. “Executions of migrants who cannot pay, torture, rape, blackmail and abandonment in the desert are the order of the day there,” states the wire report to the Federal Foreign Office in Berlin. It tells of “the most severe, systematic violations of human rights.” The following words make the public listen up: “Authentic cell phone photos and videos document concentration camp-like conditions in the so-called private prisons.” Later, the diplomats explain that they chose the drastic phrasing because they learned of regular, fixed times for shootings in the camps. Some of these private prisons are in the hands of militias who control parts of the country. Islamists, militia fighters and state actors are equally entangled in the smuggling business.

Nonetheless, starting in 2016, the EU Commission allocates around $350 million for border protection in Libya until mid-2020. This is not enough for Fayez al-Sarraj, the powerless prime minister in Tripoli. He demands nearly $900 million from the EU to stop migrants in 2017; General Heftar even calls for $20 billion a few months later. There is nothing Al-Sarraj can offer in return, since the smugglers’ bases are out of his reach.

The Italy situation

Italy does not want to accept this. Since the EU has not helped Italy, it is counting on cooperation with Libya. Italy is the only EU state with an embassy in Tripoli. At a meeting on 3 February 2017, al-Sarraj promises Italy’s Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni to better control the borders and to set up camps from which refugees are to be returned to their home countries. Italy offers money.

One day the same day later, the EU heads of state meet in Malta. For the first time, they question the taboo against sending people back to Libya. They decide that Libya should now have more border guards, more training and new camps, which they call “adequate reception capacities and conditions for migrants.”

Within a few months, everything is set in motion. Italy’s EU ambassador Maurizio Massari had threatened the EU with closing Italy’s ports but achieved nothing, so Europe probes the Libyan option, which it had avoided until then. The so-called Libyan coast guard receives inflatable boats, jeeps, buses, bulletproof vests and communication equipment from the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF). The consequences are fatal.

On August 15, 2017, the Golfo Azzurro, a boat of the Spanish sea rescue NGO Proactiva Open Arms, nears the Libyan coast. Around 5pm, a Libyan Coast Guard boat arrives. Its identification number ‘654’ is visible on photos: it is one of six ships of the Bigliani V series that Italy supplied to Libya in recent years. It heads towards the Golfo Azzurro. Ricardo Gatti, 39, formerly a social worker on Mallorca, now commander of the boat, summons the crew below deck. The Libyan boat heaves to. Men with guns are on board. They make radio contact in English, demanding an “authorization” from the Libyan government. “We don’t have one and we don’t need one,” Gatti replies. The Libyans want to come aboard; Gatti refuses. Then the Libyans order the Golfo Azzurro to follow them, to Tripoli. Or “we will target you,” they threaten, as Gatti reports. The Golfo Azzurro complies. “We knew that once we got to Libya, our ship would be gone,” says Gatti.

Gatti uses a satellite telephone to call the Spanish and Italian Ministries of Defense, the EU Operation SOPHIA headquarters and the assistant to the then President of the European Parliament Antonio Tajani. Finally, after about an hour, the Libyans stop. The Golfo Azzurro is allowed to turn north. “’If you come back, we'll shoot,’ they said,” Gatti reports.

It is the second incident of this kind within a few days. On 8 August, the Libyan boat ‘654’ had approached another Proactiva Open Arms rescue ship. A video shows the coast guards firing a machine gun into the air, obviously to drive off the sea rescuers. According to Gatti, this incident also occurred in international waters. “We’re really disturbing the EU, but we’re not leaving. So now they’re sending the Libyans,” Gatti says.

A short time earlier, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) in London received a letter from the Libyan government. The letter declares that Libya will now be responsible for emergencies in the southern half of the maritime area between Libya and Italy. While this is the international standard, Libya has been unable to comply, so Italy coordinates rescue operations up to the 12-mile limit off Libya’s coast. That was to end now. “No foreign ship has the right to enter” the area without authorization, said General Abdelhakim Bouhaliya, commander of the Tripoli naval base.

His forces will now cruise the Libyan coast. When they spot refugees, they stop them and bring them back. After a brief treatment by the UN organizations UNHCR and IOM, the refugees go straight back to hell: to the internment camps of the Libyan interior ministry’s Department for Combatting Illegal Migration (DCIM). Reports of “extremely serious human rights violations” are credible, states the German Federal Foreign Office. The camps are characterized by “heavy overcrowding, poor sanitary conditions, food and drug shortages.” Journalist Michael Obert reported on inmates’ horrifying descriptions from one of the camps near Zawiya. Bloodstained women told him about mass rapes, he writes. The German Foreign Office states that it is “not possible” to track what happens to people after they enter the DCIM camps. Amnesty International estimates that about 20,000 people were returned in 2017. As of August 2018, the figure already reached 29,000, according to a report by the UN mission in Libya. Images of torture or mock shootings in the camps surface repeatedly. In November 2017, CNN released a video recorded undercover at a slave auction in Libya. Young Black men and women from the internment camps are for sale.

But the so-called Libyan Coast Guard does not stop all the refugees. So now Italy, in particular, starts targeting the sea rescuers, who are bringing the rest of them to Italy. At first everyone underestimated the private initiatives, which were mostly crowdfunded. But from January 2016 to May 2018, according to an IOM count, 301,491 people were rescued in the central Mediterranean and brought to Europe – and 97,236 of them were taken on board by sea rescue NGOs. They are one of the major actors in the Mediterranean.

And they have upgraded: A civil air reconnaissance mission off the Libyan coast is launched in April 2017. A search aircraft, type Cirrus SR22, funded mainly by the Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD), Germany’s official Protestant federation, is stationed on Malta and named after the migratory “Moonbird.” It is the latest project of the NGO Sea-Watch, which just recently introduced an app which is supposed to let refugees make emergency calls. This technology reinforces the NGOs in the moral trench war along the EU’s external border.

This war now has NGOs coming under fire. Frontex director Fabrice Leggeri claims that their activity “leads smugglers to force even more migrants onto unseaworthy boats than in previous years. Therefore, we should put the current concept of rescue measures off Libya under scrutiny.” Sebastian Kurz (Austrian People’s Party), at that time Austria’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, calls it “NGO madness.” Stephan Mayer, Home Affairs spokesman for the CDU/CSU parliamentary group in the Bundestag, speaks of a “shuttle service” to Italy.

The Italian government demands that the eight maritime rescue NGOs then active in the Mediterranean sign a code of conduct. This would make their work much more difficult. The German NGO Jugend Rettet IUVENTA is one of five NGOs who refuse to sign at a meeting at the Ministry of the Interior in Rome in early August 2017. On the following day, the rescue control center in Rome calls the Jugend Rettet ship IUVENTA to the port of Lampedusa. There, state prosecutors seize the boat. The charge: “Encouraging illegal entry.” Human rights organizations expect the trial against the 12 crew members to start in Agrigento, Italy, in 2019. They face up to 15 years in prison. Additionally, Italy could charge fines of nearly $17,000 per person brought into the country – and the IUVENTA has rescued just over 14,000 people.

From early 2013 to mid-2018, some 681,000 refugees and migrants arrived in Italy. Had Europe shared the load fairly, Italy, according to its size and economic power – about one-ninth of the EU’s – would have had to take care of about 75,000 in those five and a half years. With such a small load, the Italian mayors who started sit-ins or even hunger strikes so that their municipalities would not be assigned any more refugees would have been considered Nazis, or insane. But the real imbalance allows politicians like Simone Dall’Orto, the Lega Nord mayor of Traversetolo near Parma, to blame the EU and threaten to go on hunger strike against more migrants. Many local politicians followed his example.

By 2015, the EU agreed to take on a total of 160,000 refugees from Greece and Italy in the following years, 45,000 of which were to come from Italy. Even that would have been insufficient, but the EU never followed through. Hungary and Slovakia took legal action against the agreement but lost – and still refused to take a single refugee from Italy. Seven other states did not appeal, but also did not accept a single refugee by the end of the program in October 2018. Overall, the so-called relocations to other EU states reduced Italy’s burden by just 12,706 refugees – only about a quarter of the paltry number promised.

Already in 2017, the Italia government had turned to use unprecedented methods to stop the migration movements across the Med. The minister of interior, Minniti, travelled to Libya with suitcases full of Euros in order to persuade not only the militias of the coastal regions of West Libya to cooperate, but he also visited militia leaders in the desert regions of the south and tried to make them people hunters instead of people smugglers. Minniti, unlike his successor Salvini, had large intelligence networks and capabilities. His cooperation with the militias went hand in hand with initiatives of European governments in the Sahel region in the wake of the Valletta Process.

While, with Minneti, Italy started a very efficient informalization of anti-migrant policies, his successor was a man of strong words and symbolic gestures. In the Italian parliamentary elections of March 2018, the populist Five Star Movement (Movimento Cinque Stelle, M5S) and the far-right Lega Nord both win a narrow majority. Soon afterwards, the interior ministers Horst Seehofer of Germany, Matteo Salvini of Italy and Herbert Kickl of Austria meet in Innsbruck. They discuss matters that would have been utterly impossible until recently: Austria wants to ensure that no more asylum applications can be filed on European soil. Salvini asserts that he will reject all ships with rescued refugees. The main goal is “to reduce arrivals and increase the number of deportations,” he says. This is all that matters now.

If 2015 was the summer of migration, then 2018 is the summer of isolation. An axis of far-right governments, from Rome through Vienna to Budapest, is now in power. And the media are playing into it. The German weekly Zeit publishes a pros & cons essay titled “Or should we just keep out of it? Private helpers rescue refugees and migrants at sea. Is this legitimate?” This question, in one of the most reputable newspapers on the continent, shows how far the debate has sunk.

“Suddenly, there are two opinions on whether to save people in mortal danger or to just let them die,” writes the Süddeutsche Zeitung, and calls it “the first step towards barbarism.” The words quickly cause a stir, but they miss the mark. The debate is not new, but now those who prefer not to rescue are in power. They have created conditions that allow them not only to flaunt this view, but also to brazenly act upon it.

On 1 July 2018, Captain Pia Klemp of the vessel Sea Watch receives an email from the Maltese Port Directorate: the boat is forbidden to sail. The ships Lifeline and Seefuchs and the search plane Moonbird are also banned from setting out. The Maltese government briefly explains that it must “verify that all who use our ports comply with national and international standards.” Why is there any doubt? And why now? At the same time, Mission Lifeline captain Claus-Peter Reisch is accused of not registering his ship properly in Malta. Reisch’s attorneys reject the charge. Other ships are abruptly deprived of lose their flags registration.

For a long time, Malta struggled with the mass arrivals of refugees. The number of people taken in by other EU states was insignificant. In 2014 Italy finally promised the island state to take in those picked up in Malta’s rescue zone. The two countries never officially confirmed this agreement.

But now this arrangement is over. In June 2018, Italy turns away the Aquarius from the German NGO SOS Méditerranée. After an odyssey lasting for days with 629 people on board, the boat is allowed to dock in Spain on 17 June. Next, Italy rejects the Lifeline, which is carrying 233 people. Italy wants the shipwrecked migrants returned to Libya. But the rescue groups strictly refuse to expose the ships’ passengers to the abuse and imprisonment in Libya. The Lifeline has to dock in Malta. The island’s government fears a precedent.

In the 72 hours before the Lifeline arrived, Maltese politicians made every effort to ensure that the refugees could travel on to other EU states. Malta, a country of 122sq meters, population 432,000, had to negotiate on its own what the entire EU has failed to achieve for years: an effective distribution system. “It was an insane challenge,” says an official on staff for Prime Minister Joseph Muscat. Alone, Malta probably could have accommodated the Lifeline’s 230 people, maybe even another thousand, but not many more.

There were days in 2018 when rescue ships pulled 5,000 people from the Mediterranean and brought them to Italy. “Now everyone in Europe is saying: Our country first. What are we supposed to do?” asks a Maltese official. According to government insiders in Valletta, Italy used to be the biggest ally, but not anymore. Though nobody says it openly, this is the real reason why Malta is blockading the sea rescuers, not some faulty registrations. Malta was the rescuers’ base as long as the refugees could go somewhere else: to an Italy under social democratic rule. But now, others are running, not just Rome.

So, the rescuers are chained up in port. There are times when no rescue ship is at sea. Italy now frequently refuses responsibility for emergency calls and refers them to the Libyan Coast Guard.

The death toll in the Central Mediterranean among those who reach Europe is still rising. In the first half of 2017, one person drowned for every 38 who made it. In the first half of 2018 it was one in 19 and in June, one in seven.

In March 2017, when Italy was still under social democratic rule and receiving refugees but demanding relief, a high-level EU official explained to a group of journalists how Europe intended to deal with Italy’s complaints: For the time being, everything would remain the same. There was “no majority” for other options.

On 25 August 2018, Italian prosecutors opened an investigation against Minister Salvini for kidnapping, illegal detention and abuse of power. On his personal orders, refugees had been detained on the Diciotti, a ship belonging to the Italian Coast Guard. On 16 August 2018, the ship had rescued 190 migrants from the Mediterranean Sea in compliance with international sea rescue rules. Salvini’s office head is also under investigation, because the Aquarius, with 629 rescued passengers, had been denied entry to an Italian port.

Civil society is not giving up, either. In summer 2018, the German Seebrücke (Sea Bridge) solidarity movement brings hundreds of thousands of people to the streets against Salvini’s policies. Following appeals from celebrities, NGOs receive six-figure donations – and can afford new ships. The pressure forces Malta to let the ships go. In early November the new private rescue ship Mare Ionio, sailing under the Italian flag, reaches Libyan coastal waters. The Bavarian-based NGO Sea-Eye acquires a bigger ship for new rescue missions. The Sea Watch 3 is also sailing again, as is the Spanish NGO Open Arms. Even the Jugend Rettet activists, whose ship was confiscated by Italy and who are facing heavy fines, want to continue: “We are now considering options for a new deployment,” says spokesperson Kira Fischer.

But where the rescuers can take their passengers remains to be seen. Over the winter, rescue ships have to cruise the sea again, sometimes for weeks, because no country will let them dock with the refugees. Now the European Commission wants to set up “regional disembarkation platforms” in North Africa – but no country is willing to host these camps. The EU keeps mentioning Tunisia, but President Béji Caïd Essebsi calls it “out of the question.” His country “does not have the capacity to set up such centers and to carry Europe’s burdens,” Essebsi says. “Here everyone must bear their own burden.”

But nobody in Europe wants to do that anymore.

Matteo Salvini, head of Italy's far-right Lega Nord (LN), made good on his most crucial election promise just days after taking office as deputy prime minister and interior minister. In June 2018, he declared that Italy’s ports would no longer allow ships to enter if they carried migrants rescued at sea. The only way that sea rescue NGOs would see Italy would be “on a postcard.” He would prohibit fuel supplies to these organizations’ ships. Foreign naval ships carrying rescued refugees would also be denied entry. The previous administration had agreed to accept all migrants rescued by EU patrol vessels. That was no longer the case, said Salvini. “With our government, the music has changed.” This was the escalation of a decade-long policy dispute, in which the EU had consistently abandoned Italy for too long. Italy’s Ambassador to the EU, Maurizio Massari, had already threatened to enact this measure a year earlier, on 28 June 2017. If the EU wished to avoid closed ports, it must pay for Libya to expand its coast guard, Massari urged. Above all, he demanded, the other EU states should accept significantly greater numbers of refugees from Italy and ships carrying refugees should call at the ports of other EU states in the future. Berlin, Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam and Madrid respond at the EU summit in Tallinn a few days later. They say no. But the interior ministers agree to a plan presented by the EU Commission in Tallinn. Apart from the objectives for Italy, the plan comprises 19 points, 11 of which do not affect the EU per se. These are border management measures in African countries such as Libya, Tunisia, Egypt, Mali or Niger.

In Malta, this continuous refusal led to the small island state starting to lock the arrivals in prison-like camps. These are now so full that the inmates set fire twice in January 2020 in protest.

The Post-Salvini years and the „Malta-Protocol“

In Italy, in the summer of 2019 the government of Lega and Five Stars broke up. The new coalition of 5S and PD started negotiations with Malta, France, Germany and the EU Commission. A so-called „Malta Declaration“ set the rule, that all migrants rescued from Libya by the private rescue ships were to be distributed among the participating countries for their asylum procedure within four weeks. Germany wanted to take one quarter of the rescued persons.

The governments of Italy and Malta can therefore decide whether to trigger a "redistribution case" and request European assistance. This is how it works: In the case of Italy, for example, Pietro Benassi, the advisor to the Italian Prime Minister, sends an E-mail to Paraskevi Michou. The Greek woman heads the Directorate General for Migration and Home Affairs at the EU Commission. She then writes to the so-called contact points in the governments of potential host countries. These are currently (March 2020) Germany, France, Portugal, Luxembourg, Ireland, Finland, Norway, Belgium, Spain and Sweden. It is a kind of coalition of the willing in terms of admission, consisting of one third of all EU states.

In Germany, Michous mails go to the foreign policy advisor of Chancellor Angela Merkel, Jan Hecker. Michou asks for so-called "Pledging Exercises" – the states should say how many of the shipwrecked people they want to admit. Michou forwards the feedback to Rome or Valletta. The cumbersome procedure takes days. In the fall 2019 Interior Minister Horst Seehofer had pressed for other states to agree to a blanket admission in order to make the constant negotiation of individual cases superfluous. But at the meeting of interior ministers in October 2019 in Luxembourg, no state wanted to get involved. And so Michou must continue to write e-mails – and the refugees must wait.

Once the Brussels diplomats have clarified the question of the places of refuge, Patrick Austin will be on the scene. Austin is head of department at the European Asylum Office EASO. Hardly any other EU authority is growing so fast at the moment. This also has to do with the fact that in the future Austin is to take care of the further distribution of asylum seekers within Europe more often.

Because "chaos reigned for a long time," says Austin. There were indeed the promises of admission. But Malta and Italy had to take care of everything themselves until at some point, months later, some of the refugees traveled on to other EU countries. They were not really relieved. Since the "Seehofer Plan" of fall 2019, there is now an established procedure for how this redistribution is organized. That is Austin's task.

Together with the EU border control authority Frontex, his people record the arrivals biometrically and register them in the databases of the countries of arrival. They appoint guardians for unaccompanied minors, and only these are usually allowed to stay in Italy. The EASO officials ask the arrivals if they want to apply for asylum. "So far everyone has said yes," says Austin. This is no wonder: without the application, deportation is imminent. The same applies if the arrivals do not agree to a further distribution.

Finally, Austin's employees draw up a list with a proposal of who should be sent on to which country. Today, there are also fixed criteria for this: Relatives in one of the host countries or "cultural ties", such as language skills. Sick people, minors, the elderly or people with mental health problems are divided as equally as possible. This is intended to prevent some countries from choosing people with good integration prospects and others from having to accept many people whose care is costly.

The states then examine the candidates. France, Ireland and the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees in Nuremberg (BAMF) send their own asylum officers to the hotspots for interviews. Luxembourg and Finland, for example, are content with a video conference. In addition, there is a security check. After that, the people can carry out their asylum procedure in the host country. In theory.

But everything is voluntary. „There is no legal obligation," says Austin. Germany, for example, has taken in around 500 people in this way between 2018 and January 2020 – 174[53] from Italy and 327 from Malta. But if the states say no to individual refugees, they get stuck in Italy or Malta. The EU Commission has made a commitment to the two states to ensure that all shipwrecked persons for whom places were promised actually leave the country. But it does not have any leverage. „Welcome to the world of diplomacy,“ says Austin.

On the one hand, Italy and Malta are now relying heavily on cooperation with the so-called Libyan coast guard: the latter is to stop the refugee boats and bring the inmates back to Libya. At the same time, however, the Italian and Maltese coast guards are also rescuing the refugees themselves, without the rescued people being redistributed. The same applies if refugee boats make it to Europe under their own steam.

Around 2,688 people arrived in Malta between January and the end of July 2021. In Italy, 23,300 people had arrived by the end of September, only a fraction of which came in private aid boats. Only these are covered by the EU redistribution mechanism. One could also say that despite the "Seehofer Plan" the two countries must continue to bear the bulk of the problem alone. And so, the two states are not wrong to insist that at least those rescued by the private ships are quickly absorbed by the rest of the EU.

Many observers think it is obvious that all these bureaucratic hurdles are an arrangement in order to block NGO rescue on the Med. It is a spectacle in which Italy, Malta, and also willing states take different roles in one and the same drama. If not so, Italy and Malta could just do what the Berlusconi Government did in 2012: Give papers to the boat people and let them pass.