RefugeesInLibya: An Unheard Mass Protest and Update March 2022

April 7th, 2022 - written by: Migration-Control.info

In December 2021, Dorothée Krämer wrote a blog entry for migration-control.info about the self-organized protest movement of the Refugees in Libya. Doro's text was originally published in German (RefugeesinLibya: Ein ungehörter Massenprotest). We translated the blog post and added a short update of the events that have taken place since December.

Update March 2022

On 10 January 2022 Libyan militias raided the informal settlements of about 1,000 refugees in Tripoli, in front of the UNHCR office, where they have been protesting for over three months. Violence was used against refugees, people have been beaten up, shot and tents were set on fire. It seems that the raid was conducted by the DCIM – the Libyan Department Against Illegal Migration – but also militia groups like the Janzour group. More than 600 refugees were then arbitrarily detained in the Ain Zara detention centre. The MSF team who aided some of those detained later communicated to “have treated patients with stab wounds, beating marks, and signs of shock/trauma caused by the forced arrests. Among them there were people who had been beaten and separated from their children during the raids”.

The raids that led to the detention of more than 600 people were the first public actions of the new head of the DCIM, Mohammed Al-Khoja. Al-Khoja is also a militia leader who has been accused of many occasions of trafficking and smuggling of human beings. Moreover, one of the most infamous detention centres where migrants are held – Tarik Al-Sikka – is owned by al-Khoja himself. (https://euromedrights.org/migrants-and-refugees-in-libya/)

Since January 10, the Refugees taken to Ain Zara have been subjected to ill-treatment, inadequate unhealthy food, unhealthy drinking waters, and unsanitized places to sleep in.

To this day the responsible NGO (UNHCR LIBYA) declined to give comments on why it forsook its refugees in the streets for over three months of unimaginable chaos and then to the hands of the militias. (https://www.refugeesinlibya.org/post/i-will-return-them-to-your-headquarter-in-three-days-time-says-afandi-hakim-of-ain-zara-prison)

Mid February 22: A group of asylum seekers staged a four-day hunger strike to protest against what they say are inhuman living conditions. Several people became too weak to stand and lay on the floor during open-air time. At least eight of them were brought away by security guards and militia officers controlling the centre, according to the testimonies of the three asylum seekers. Their fate is unknown. (https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/2/23/inside-ain-zara-where-europes-unwanted-are-disappeared)

On 13 April, Refugees in Libya published an online conversation as part of the protest action "It's time to listen", in which activists on the run address the conditions they and many other people are facing in Libya.

Refugees in Libya: An Unheard Mass Protest

Originally published in December 2021 by Dorothée Krämer. The author researches and writes on border violence and counter-mobilisation, among other topics as part of the independent news blog Are you Syrious? The pictures are taken from RefugeesinLibya or their Twitter-Account, if not labelled differently.

The international community ignores the years of hardship for the refugees in Libya. The UNHCR’s policy space is small; for most people it can do nothing. Thousands of refugees are left to fend for themselves, in a constant cycle of detention camp system, escape and re-arrest. Yet despite the catastrophic situation, they manage to organise themselves and draw attention to their situation.

“Jean Paul, tell the international community that you are not able to protect the people in Libya under the mandate of the UNHCR!”

If they are to be left to their fate, the world should at least know this truth. Yambio David Oliver Yasona is angry and disillusioned. Resignation is a privilege of those who have alternatives. He, and the people who have been stuck outside an UNHCR building in Tripoli for weeks, are not among them. At times, 3,000 people have been waiting outside a United Nations Refugee Agency building after thousands of people managed to flee one of Libya’s infamous detention camps in early October. Hoping for minimal assistance and safety from arbitrary arrests, they turned to the UNHCR.

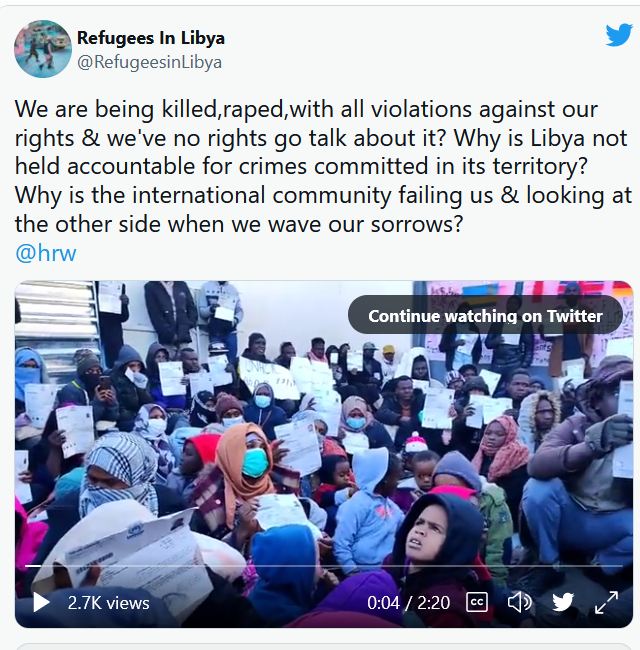

Since then, week after week has passed without anyone taking care of them. The situation on the ground at the UNHCR Community Day Centre is precarious: people are sleeping on the side of the road, without tents, without toilets. They are under-supplied and in constant fear of attacks by militias. Among them are many children. Diseases are circulating. Three people have already lost their lives, right in front of the UNHCR building. At least one child was born there on the street. The refugees have hardly received any help so far; instead, the UNHCR suspended support activities at the centre. The head of the UNHCR mission in Libya, Jean Paul Cavalieri, repeatedly calls for this temporary camp to be closed – without offering the people on the ground a safe alternative. He accuses the demonstrators of making the organisation’s efforts to provide for the most vulnerable refugees impossible through their presence and protest. The refugees clearly disagree and accuse the UNHCR of leaving them without help.

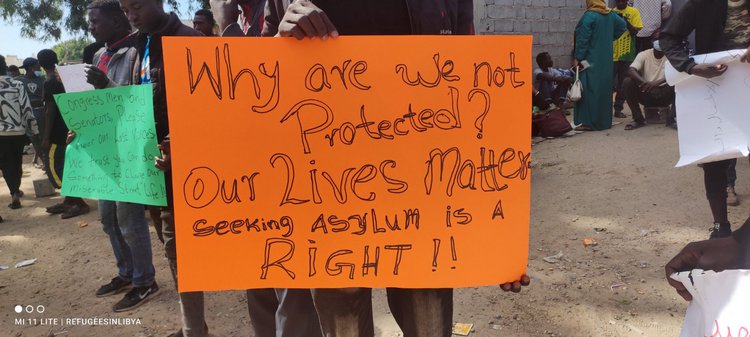

For weeks, the refugees have been demonstrating daily on the ground, with chants and banners in four different languages. Through Twitter (@RefugeesinLibya) and Facebook accounts (@refugeesinlibya) as well as a website, they have built up their own communication channels through which they try to capture the attention of the international public. They insist to finally be heard and make clear political demands: The liberation of all refugees held in Libya’s detention camps, as well as safe accommodation and evacuation from Libya as soon as possible. They condemn the support by the European Union of the so-called Libyan Coast Guard and the camp system and the inaction of the international community, including the African Union. They are particularly harsh in their criticism of the UNHCR, the organisation whose mandate is to protect them – and which, instead of standing behind them, is now using the protestors as scapegoats.

History of the protests in Libya

The current protest is not the first of its kind in Libya. In recent years, refugees have repeatedly organised themselves to fight their desperate situation. In March 2019, for example, a protest in Camp Sikka was violently repressed by the police. As a result 50 people were injured. In June 2019 the journalist Sally Hayden published pictures from Zintan Camp, where 22 people had died of malnutrition six months earlier. The prisoners were demonstrating, hands into fists, crossed over their heads tilted towards the ground. On banners they had written with tomato sauce: “Why the UNHCR ignores our tears in Libya?”. In front of them in the hall where they spent days and nights was a huge pile of rubbish from which flies rose. Fleeing to UNHCR buildings in the hope of international attention and safety is also not new: after 53 detainees were killed during an airstrike on Camp Tajoura, and the UNHCR later evacuated only 55 of the remaining 360 people from the camp, a hunger strike ensued. 350 persons were eventually released. They sought shelter at an UNHCR facility where the extremely vulnerable refugees who were selected by the UNHCR evacuation program were temporarily housed. Initially, UNHCR provided shelter for the new arrivals, but as more and more people arrived and the security situation deteriorated dramatically due to the prevailing civil war, the facility was closed.

Those who persevere and demonstrate in front of the UNHCR Community Day Centre in Tripoli today show great endurance and mobilisation capability. But still, it looks like their outcry will once again be ignored. The situation is messed up. In early December, the UNHCR announced that it would give up the building at the end of the year. No one has an answer to where protesters should turn when the United Nations flags at the Community Day Centre have been taken down and they are defenceless against renewed arrests.

Libya as a legal vacuum for refugees

The situation for refugees in Libya has been catastrophic for years. Survivors report an endless cycle of arbitrary arrests, detention camps, torture and forced prostitution. A recent UN report found that refugees heading for Europe face an endless chain of abuse as soon as they set foot on Libyan soil.

There is no right to asylum in Libyan law, as required by the Geneva Refugee Convention. Libya has never signed onto the Geneva Refugee Convention and acts in clear contradiction of its content. Refugees are regularly deported from Libya without verification of their eligibility for protection. The Libyan law even goes further: Law No. 19 of 2010 renders illegal all irregular entry, stay and exit and enables unlimited imprisonment with forced labour and subsequent deportation for all “illegal migrants”. Thus, there is effectively no possibility for refugees to stay in the country legally, no matter what they are fleeing from. They are people with no rights and no means of protection against arrest and exploitation. In a country battered by years of dictatorship, international intervention and militia warfare, there are people who profit from their desperate situation.

A look back: Libya as a hub of migration – and migration defense

The current situation in Libya can only be understood through taking into account the practice of externalising migration control, as carried out by the European Union far into the states of Africa.

In the second half of the 20th century, Libya was a destination for migrants from various countries on the continent. The economy was growing, fuelled by recently discovered oil reserves. Long-term dictator Muammar al Gaddafi cherished pan-African views, which were expressed through liberal regulations on employment migration, among other things.

In the course of sanctions by the international community, there was a collapse in economic power. Migrants were increasingly declared scapegoats and blamed for the situation. The climate became more radical and there was an increase in racist attacks. Visas and residence permits became more difficult to obtain. In the year 2000, 130 migrants were killed in pogroms in Tripoli and Zawayia. Thousands more were arrested and deported, often dropped off in the middle of the desert on the border with Chad and Niger and left to their fate. Libya became increasingly unsafe and the flight from Libya across the Mediterranean more obvious. This in turn put Italy on the map, where people arrived after the dangerous crossing. The reports of violence, deportations and internment camps did not prevent Berlusconi from starting talks with Gaddafi about taking back migrants. Similar agreements already existed with Morocco and Tunisia, in which the countries committed themselves to detaining and taking back migrants. The temporary climax of the cooperation between Italy under Berlusconi and Libya under Gaddafi was the so-called Friendship Agreement in 2008, which allowed Italy to bring refugees being intercepted in the Mediterranean back to Libya – a practice that was classified as a breach of human rights by the European Court of Human Rights in 2012. Shortly after the conclusion of the Friendship Agreement in 2010, the aforementioned law No. 19 was passed in Libya. This abruptly turned thousands of foreigners into illegal migrants who were threatened with internment.

The migration defence industry at Europe's mercy

The consequences of the Arab Spring changed the situation in Libya dramatically. To this day, there is no unified, stable government. Currently, the country is once again at a crossroads after the election scheduled for 24 December 2021 failed to be held. In this state of lawlessness, combined with militia-led war and the collapse of the economy, the exploitation of refugees through human trafficking has become a lucrative source of income for some. Over the years, a whole industry has developed in which militias have taken over the official tasks of the Ministry of the Interior and the Department for Combating Illegal Migration. This includes both the operation of camps and the interception of fleeing people at sea. In this shattered country, it is impossible to distinguish between state institutions, militias and human traffickers. To speak unreflectively about the Libyan Coast Guard is therefore just as misleading as to draw reassurance from the fact that the “official” camps are under the authority of the Ministry of the Interior. The transition between state institutions and human traffickers is fluid.

For many, the cycle of violence begins when their boat fleeing to Europe is intercepted by the so-called Libyan Coast Guard. The so-called Libyan Coast Guard ensures that no one leaves the country for Europe: Either by intercepting those fleeing, or by not responding in the case of shipwrecks – and letting the people drown. In 2021, 32 425 people were intercepted fleeing Libya, at least 1 500 lost their lives. Those who survive and are intercepted are deported to the infamous camps, which are officially under the authority of the so-called Department for Combating Illegal Migration. According to the UNHCR, there are currently 27 of these camps. In addition, there are numerous reports containing information about other, unofficial and secret camps, where conditions are likely even more dire.

According to the UN report cited above, the conditions in the camps are intentionally designed to cause suffering. It further states that "people are detained indefinitely without the possibility of having the lawfulness of their detention reviewed. The only viable option for escape is to pay large sums of money to the guards or to perform forced labour and sexual favours inside or outside the camp". Currently there are approximately 7 000 people detained in those camps. The vast majority of these camps are completely overcrowded, with inadequate supplies of food, no access to drinking water and no medical care. Toilets and showers are broken, diseases are omnipresent. Violence, torture and rape are routine. With regard to the crimes to which refugees in Libya are exposed, the UN report goes so far as to speak of "systematic and widespread attacks" that "correspond to state policy". Accordingly, these acts could be considered crimes against humanity.

Yet despite this overwhelming evidence, the EU continues to pursue its policy of outsourcing migration management. One example is the Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, a funding scheme that has been in place since 2015 and finances migration reduction projects across Africa. In Libya, these projects primarily aim to expand the capacity of the so-called Libyan Coast Guard (for details see also here and here). In this way, European taxpayers' money flows directly into the hands of militias. Large sums have been made available, for example, to set up a centre to coordinate sea emergencies, as this is required in every country involved in sea rescue. Until now, however, the centre existed only on paper; calls during emergencies at sea were simply not answered or postponed until the next day. Until recently, the Italian Navy had its own ship in Tripoli, on which the centre is to be set up in containers (Tagesschau 14.12.21). At the same time, Frontex, the European Border Agency, is working directly with the so-called Libyan Coast Guard. Journalistic investigationshave revealed that Frontex employees sent information about boats with refugees via Whatsapp to the so-called Libyan Coast Guard – even though NGOs’ ships were closer and could have rescued these boats more quickly.

The role of the UNHCR in Libya

In this situation the role of the UNHCR is anything but simple. The agency`s task is to advance the implementation of the Geneva Refugee Convention. When states are unable or unwilling to protect refugees, the agency tries to fill the void by providing direct assistance to people under its mandate. However, the relationship between Libya and the UNHCR is tense. In 2010, Gaddafi threw the organisation out of the country without much trouble. Meanwhile, the UNHCR is active again, but without a clearly defined legal agreement. Repeatedly, there are problems with the issuing of visas to staff members.

The UNHCR's mandate covers not only internally displaced persons but also refugees and asylum seekers. In the spirit of bureaucratisation, people have to register with the UNHCR as asylum seekers in order to receive basic support services. Yet registration does little to help people. The certificate they receive as asylum seekers from the UNHCR is not recognised by the Libyan authorities. Accordingly, it does not protect them from arrest and detention. Many of those who are in the camps are registered with the UNHCR. Assessment procedures on actual refugee status are only carried out in the few cases where people have already been classified as particularly vulnerable and selected for the few places in resettlement or evacuation programmes. The places in these programmes are very limited, the allocations provided by the states are completely insufficient. Currently, over 40,000 people are registered as asylum seekers with the UNHCR in Libya. In 2021, just under 1300 people were able to leave the country through evacuation or resettlement programmes. The selection criteria is extreme vulnerability - old people and people with children have the best chances, but even for them there are not sufficient places.

The UNHCR has extremely limited access to the detention camps, usually only through partner organisations. IOM and the UNHCR are often on the ground at the port when intercepted people are brought back by the so-called Libyan Coast Guard. They can try to save lives, provide some water and food, and register people – but they cannot prevent them from being taken to the camps. Nor can the UNHCR provide safe accommodation for those who have escaped the camps. In a recent interview, an UNHCR spokesperson, referring to the situation in front of the UNHCR Community Day Centre, stated that they could not provide alternative accommodation for the people staying there. Private accommodation would also hardly be an option. Many house owners would not be willing to rent to refugees, and if they did, then only at horrendous prices. At the same time, many temporary shelters were destroyed in the recent waves of arrests. When the UNHCR celebrated the release of 57 vulnerable people from Ain Zara Camp in November, protesters commented on the irony that these people had also joined the protest camp for lack of alternatives. After their release, they had received some financial support and then were left to their fate.

All that is left for the UNHCR to do is to regularly call for the liberation of all people held in the camps and for the EU to increase quotas for humanitarian visas and to link support for Libyan authorities to their compliance with human rights. But the European Union ignores these words without batting an eyelid. The UNHCR can hardly get more drastic because the EU is the second largest donor to the UNHCR after the US. Various projects specifically in Libya are financed by special funds from the EU. In a situation where thousands of people are subjected to greatest suffering under its mandate, the UNHCR becomes a silent witness with minimal space to act on behalf of the most vulnerable. (For more details on the funding of international organisations and NGOs in Libya, see Paolo Cuttitta on this blog).

The current situation: wave of arrests and outbreak

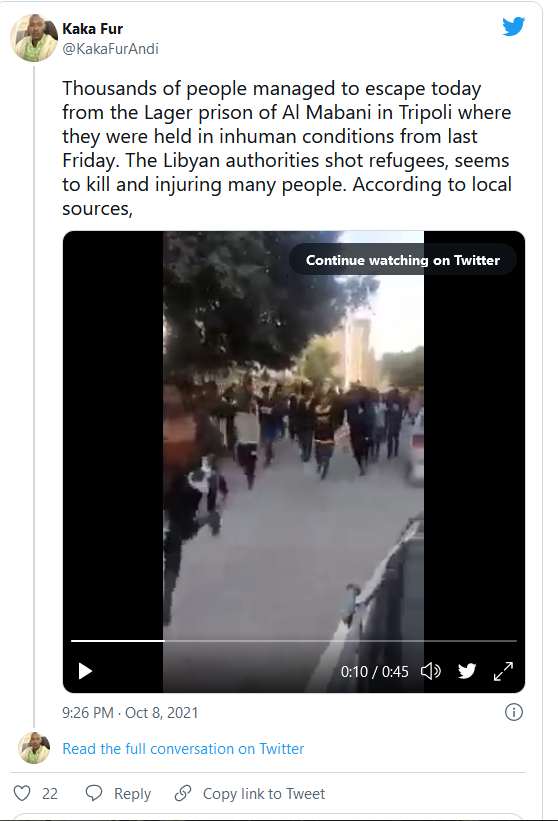

Without safe shelter every escape or release is just a short break from the next period of detention. The last large-scale operation by the Libyan Ministry of Interior at the beginning of October, which ultimately triggered the current situation at the UNHCR Community Day Centre, shows how legitimate the fear of arrest is. In the Gargaresh neighbourhood, where many refugees were living in makeshift shelters, there were massive raids in the first week of October. Thousands of refugees were arrested, countless shelters destroyed and property stolen. Pictures of the action show heavily armed men in balaclavas. They guard people lying on the ground, their hands fixed behind their backs with cable ties, their faces in the street dust. At least one person was killed in the raid. 5000 people, including hundreds of children, were arrested and taken to the camps. The already catastrophic conditions in the camps were worsened by absolute overcrowding. Al Mabani camp, where most of the arrested people were sent, was four times overcrowded. An organisation that has been given severely restricted access to the camps reports that people had to defecate on the spot on the floor because they had no access to sanitary facilities. Videos from Al Mabani circulated on social media. They show a hall full of people, lying skin to skin. One person is unconscious, another has blood running down his chest. Someone tears a T-shirt to bandage wounds. Flies buzz through the picture, there is crying, screaming and hammering against a metal door.

On 8 October, there was an uprising at Al Mabani. The exact circumstances are obscure. One witness reports that a supervisor had beaten a child, which led to a collective rebellion by the prisoners. By the end of the day, six people were dead, shot by the camp operators. Three thousand people, on the other hand, managed to escape. Yet where to flee when the next arrest is looming everywhere and the last temporary home offered no security? People turned to the one place that promised minimal hope of safety and support: the UNHCR Community Day Centre in Tripoli. In the short term, the refugees hoped for safe shelter and protection from re-arrest. In the long term, they want nothing but to get out of Libya. Since then, more than two months have passed without the UNHCR taking up their cause.

The trust in the UNHCR is betrayed

The relationship between the UNHCR and the protesters is tense, to say the least. Instead of support, only harsh words came from the UNHCR: by their presence and demonstration, the protesters would jeopardise the evacuation possibilities for vulnerable people. Again and again, Jean Paul Cavalieri calls on people via social media to leave.

On 2 December, the bad news came: the UNHCR would close the Community Day Centre at the end of the year. The news was first published on the UNHCR Libya's official Twitter account, but was deleted again shortly afterwards. It can still be found on a Facebook page that is less focused on publicity and more on direct communication with refugees. It is true that support services in the centre have been temporarily suspended since the protests began in early October. But the building is still officially an UN building. It is guarded by the Diplomatic Police, a special force responsible for the protection of diplomatic facilities. From them, and the minimal effect of the international organisation's presence, the protesters hope for a small amount of protection against further arrests. Upon the announcement of the closure, the protesters took their protest to the UNHCR headquarters in the Sarraj district, where violent clashes broke out with UNHCR security personnel. Again, the UNHCR's account differs greatly from that of the refugees. Both speak of three injured, each on their side. In a video message to the refugee community, Jean Paul Cavalieri explains that the protesters are mostly people who are not under the protection mandate of the UNHCR and that through their protest they would hinder the work of the UNHCR. The protesters contradict this in a video that was also published, in which they hold up their certificates to the camera, which were issued by the UNHCR and identify them as asylum seekers. They complain that the papers do not offer them any protection. Among them are many women and children. At the same time, the demonstrators published videos showing heavily armed security personnel violently confronting the angry people. On December 20, activities at the UNHCR centre in Sarraj were also temporarily restricted.

Meanwhile, the alliance between the Libyan camp system and the international community, led by the European Union, is ongoing. José Sabadell, the European Union's ambassador to Libya, recently clarified their priorities on Twitter: he was concerned that the current situation in front of the UNHCR means that the UNHCR is being prevented from doing its work. The Libyan authorities were called upon to ensure security and to protect staff and buildings. Not a word to the protesters, not a word about the fact that it is the Libyan authorities who make the lives of these people a living hell every day.

So it looks as if nothing will change regarding the situation of the refugees in Libya. The most likely scenario is that everything will start all over again for them: makeshift emergency accommodation, then another arrest, on land or during the escape at sea. If the boat doesn't sink: camps, forced labour, torture, with luck another escape and so on and so forth. The world will forget them again. As long as the European Union sticks to its policy of outsourcing migration control and supporting the camp system, nothing will change. It is time for the UNHCR to acknowledge this and to find the courage to stand behind those it was founded to protect. It should finally let the world know what Yambio David Oliver Yasona is demanding: that it is unable to protect the people under its mandate in Libya.

Follow the RefugeesInLibya on their Website, their Twitter, and their Facebook.