The Colour-Line through Africa

February 7th, 2026

In this text, we will summarise the latest developments in Europe's outsourced border areas. The synopsis provides an overview of the latest phase of neo-imperialist encroachment on Africa.

In 1899, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote the following sentence in his famous book The Philadelphia Negro:

In all walks of life, the Negro will encounter rejection or rude treatment, and the bonds of friendship or memory are rarely strong enough to hold across the colour line. A few years later, he wrote the following in his essay Of the Dawn of Freedom:

"The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the colour line – the relationship of darker to lighter people in Asia and Africa, in America and in the islands of the sea."

Du Bois was a traveller between worlds.[1] He knew that "race" is a cultural and historical construct with no basis in biology or skin colour. Today, 100 years later, we must acknowledge that the colour line was not just a problem of the "racial century", as Dirk Moses called the period between 1850 and 1950. Black Lives Matter is an issue that remains highly topical, across continents.

Currently, a field of tension is emerging from Europe to the South, characterised by the re-emergence of the colour line running through the Sahara. The current global crisis of economic stagnation and rearmament, in which the digital transformation of capitalism remains uncertain, comes down to many regions of Africa as a period of extractivism, war and displacement. Borders have become zones of necropolitics.

Racism as Migration Management

We see a cascade of racism, from the Brandenburg marshes and the Dresden hinterland, to the Italian Alpinisti and Fraternelli, to the Libyan militias, the Guardia in Tunisia, and the butchers in Darfur, we see a cascade of racism in which racism based on skin colour is also resurgent.. The colour line through Africa forms part of a European cordon which is designed to confine Black Lives in areas of war and displacement. We are witnessing a racialisation of the mobility regime, which begins with visa regulations and is characterised by "Torture Roads" and push-backs to the south.

The racist stratification of space evokes the idea of colonial continuity. Racism based on skin colour dates back to the enslavement of Africans, becoming overlaid by colonial racism in the second half of the 19th century. The ideology of white supremacy, which is currently experiencing a resurgence in the far-right spectrum and is being propagated alongside the market liberalism of Hayek's Bastards, perpetuates this theme. This ideology is a reaction to feminism, diversity and the Black Atlantic. At the same time, it is being used as a weapon against the migration movements of recent decades.

When we speak about racism in Europe, we must consider Antisemitism at every point. Since the Middle Ages, there have been repeated racist excesses against the Jewish diaspora.[2]] Antisemitism became modern when it turned against the subsistence culture of the Schtetl and against the refugee movements of the impoverished Eastern Jewish population.[3] From today's perspective, colonial crimes are also overshadowed by Nazism. The Nazi Ostpolitik was part of a long colonial tradition and must be discussed in this context.[4] Since "Charlemagne the Saxon Slayer" since 772, colonial expansion has followed a "drive to the East". In the "General Plan East," the extermination and exploitation of populations and territories reached a dramatic climax.[5]

Antisemitism makes it clear that racism can be invoked also without the spectrum of skin tones, and also as "socialism of the stupid". Sometimes it was about the supposed defence of a wage differential, as in anti-Irish racism in England and North America, or anti-Slavic racism in Germany, sometimes it is about hatred of "foreign" modes of reproduction, as in anti-Gypsyism. Since the 1990s, migrants in particular have once again become the target of racism across Europe.

This "new racism", which A. Sivanandan and Liz Fekete have impressively described in Race&Class,[6] is essentially a state-induced racism that is staged in the media and implemented through state policies. In fact, in Europe, and to some extent also in the Maghreb, it is not solely and primarily about racism based on skin colour, but rather about racism of migration management. It is about regulating labour markets (the "multiplication of labour") and consolidating the immense income gap betrween North and South.[7] The legitimisation of the far right through the rejection of refugees is partly desired and partly accepted.

It is the politics of a new centre ground. The less certain the circumstances, the greater the desire for national reassurance. But the majority of voters is a poor argument. Let us remember the words of Aimé Césaire from Discourse on Colonialism, that the greatest criminal is not the ideological fanatic, but the European bourgeois, the 'decent fellow next door', because for over a century he tolerated colonial abuses: the wars, the torture and the mass deaths, by approving the harsh measures of politicians.

The Cordon is not Stable.

In January 2024 the New York Times published a summary article entitled: 'Living Through Hell': How North Africa Keeps Migrants From Europe. It states that

Libya deported more than 600 men from Niger last month as North African countries — funded by the European Union to combat migration — have stepped up the expulsion of people from sub-Saharan countries.

As anti-migrant sentiment grows across Europe, from France to Germany to Hungary, citizens from sub-Saharan Africa attempting to reach the continent are being pushed back by North African governments on a scale not seen in years. The EU has signed bilateral agreements with Tunisia, Morocco, Libya and Mauritania that include financial support to “stem the flow of migrants”.

The strategy seems to be working: according to the latest data from the EU border agency Frontex, illegal border crossings fell sharply in 2024.

This article highlights a dynamic development. Europe needs migrants, not only in the labour markets, but above all to revitalise society and finally finally leaving the colonial legacy behind. New York is our beacon. The number of migrants reaching Europe has been declining in 2024 and 2025. However, the Central Med route is not yet broken, despite all the suffering and drowning. And, as a report by Mixed Migration Centre MMC notes:

The recent decline in numbers is likely to be a short-term fluctuation rather than the beginning of the end of irregular sea crossings to the EU. The urge to cross the Mediterranean or the Atlantic to reach the EU is likely to remain constant, if not increase. [...] The rigorous policy has not prevented irregular migration and has only increased the risks for migrants.

A big mess, as in any time of major upheaval. The EU is relying on the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), and it cannot be ruled out that the ever increasing restrictions on the right to asylum could lead to asylum losing its significance as a medium for trans-Mediterranean migration. Perhaps this is the end of an era that began in 1948,[8] and is ending with the crisis of liberal democracies.

But much remains open. Already before, in the 2000s, the EU believed it could organise the Mediterranean region according to it’s interests. Then came the uprisings in 2011, then came the long summer of migration in 2015. Europe's fight against migration cannot be won with or without Frontex. New routes will open up, like recently the one from Eastern Libya to Crete. It is bad enough that despots like Haftar and Lukashenko appear to refugees as their last resort.

Meloni's initiatives will not pacify Libya.. The European-Egyptian memorandum is built on desert sands. Tunisia is not safe, and Saied will not live forever. In Morocco, Gen Z's discontent cannot be appeased by repression and prestigious investments alone. The billions that the EU spends on externalisation and containment do not benefit the population in the Maghreb, let alone the Black population. The situation in the Sahel is more unstable than ever: more people are being killed and displaced in Darfur than ever before. In the AES (Confederation of Sahel) states, the war against the jihadists is depopulating large areas. The UNHCR recorded 4 million displaced persons there. The Gen Z of these states is burning in militia wars. The military regimes of the Sahel Alliance and Chad get no EU-money and have no interest in stopping migrants, yet the chronic wars are blocking the migration routes.

There will be no permanently closed borders. No amount of EU funding could secure them. But what will immigration look like when the asylum system no longer functions? Irregular migration will increase, bringing with it all the suffering that this entails. Anti-racist projects will have to adapt. Migration studies and paid social work will become less prevalent, while projects in the grey areas of society and, above all, projects promoting self-organisation among migrants will become more important on both sides of the Mediterranean.

The Belt of Wars

In our blog posts on the Sudan war and the Emirates, as well as Talk About El Fasher, we have described the connection between displacement, extraction, land grabbing and war. Not only are the Emirates fuelling this war through the gold and arms trade, they are also interested in land grabbing through displacement. This is not an isolated case. We must extend this analysis to include recent developments in the Sahel and other rregions, such as the Horn of Africa, eastern Congo, northern Mozambique.

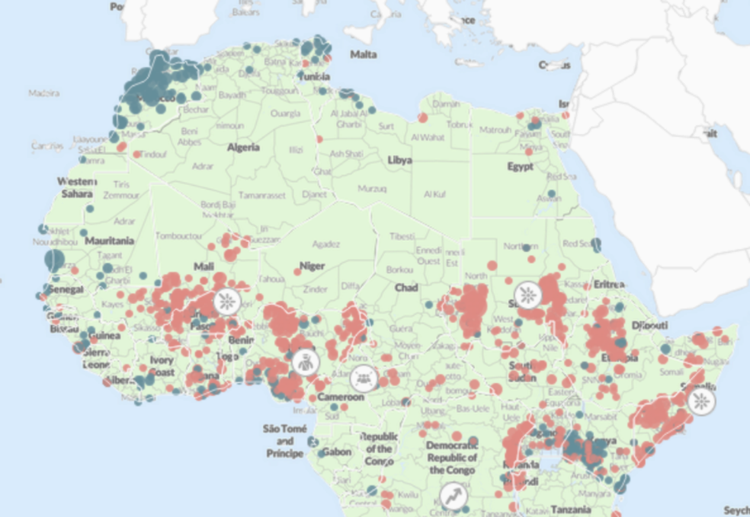

The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) recently published a map showing red-dot-marked belt of wars across Africa. As we know, there is not one but many reasons for the concentration of armed conflicts in this region. The most important causes of conflict include:

- climate change and the restriction of pastoral economies,

- the failure of post-colonial states and the rise of warlordism, including under the guise of the military, and the greed of many members of the political class,

- the rise of regional imperialist actors, primarily the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Turkey, but also China and Russia (and also USA are coming back),

- the spread of mineral and land grabbing as an economy of "real values" since the 2007 financial crisis.

- The increasing focus of large investors on African resources is another cause of conflict,

- also the European hunger for "clean" energy and the protection of nature in a "green war", and

- the role of transnational jihadism.

The European policy of containment is another very important factor. When migration routes are closed, young men are forced to work in the gold mines or join a militia. European commentators often cite population growth as the primary cause of poverty and war. These are classic racist patterns of argumentation. Rather than being perceived as a labour force for the future, the population is seen as an obstacle to investment. An economy which David Harvey has described as an economy of accumulation through expropriation, has more than ever been engaged in a war against the reproductive economy of the impoverished population since the 2007 crisis.

All forms of "War Capitalism"[9] in the belt of wars have one thing in common: the definition of populations as "superfluous". This overlaps with the ideology of far-right market liberals (Hayek's Bastards), which is based on “White Supremacy” and values biology, racism and population policy highly. They are concerned with "race, gold and IQ". MAGA, big capital and war profiteers, regional powers and nationalist military regimes are transforming entire regions of Africa into "new frontiers" in a global race for resources at a time of peak oil, peak soil, peak water and peak nature.

Although Europe is deeply involved in this process due to colonialism, it is no longer the most important player; rather, it is an accomplice, taking advantage of windfall profits and supporting European interest groups, but above all by closing escape routes and containing the population in war zones.

One could argue that the belt of wars was caused by failed revolutions. The deaths of Lumumba in 1960 and Sankara in 1987 are significant events , but even more important, in our view, are the "uprisings in Africa" in the 2010s: "Widespread urban uprisings by young people, the unemployed, trade unions, activists, writers, artists and religious groups challenge injustice and inequality. They "spread across national borders and regions, even crossing vast distances from Egypt to Uganda, Senegal to Malawi, South Africa to Nigeria."

These uprisings were about the right to a dignified life and prospects for the future, not about "development" or "nationhood”. They were collective actions by "ordinary people", particularly young people, against corruption and political wheeling and dealing. Born of imagination and the will to live, these uprisings continue in the revolts of Gen Z. There are good arguments for interpreting these uprisings as "encroachment", as Asef Bayat did in relation to the Arab situation in 2011. However, in all these movements, the question remains open as to what happens after the regime is overthrown. Perhaps the neighbourhood committees in Sudan could have developed into a "missing link" between uprising and revolution?

Over the past 50 years, the most important social movements have included not only uprisings, but also migratory movements: to the cities and metropolises (and back). As Mbembe and others have told us, forming diaspora communities is one of the key skills of many Africans. People migrate to escape violence and hunger, to see the world and find a better life, and to support their families. They carry the moral economy of their village, compound or slum into the world. Paul Gilroy spoke of "moral economies in the culture of the Black Atlantic".[10] The "cosmopolitanism of small migrants"[11] could be one of the most important social forces of change, in Europe and beyond.

The European Cordon

Following the withdrawal of MINUSMA, Europe is no longer one of the main players in the belt of wars. Europe's role in maintaining the war zones is to deploy FRONTEX, supply surveillance technology and distribute funds for prisons and border protection.

Since the economic crisis of the 1970s, the focus of efforts to curb migration has shifted from Turkey and North Africa to Eastern Europe after the fall of the Iron Curtain, then back to North Africa after 1993, then to the “Middle East” when people fled Iran, Syria and Afghanistan, and finally, since 2016, to everywhere that people have fled from. Sub-Saharan Africa has been the focus of the Khartoum Process since 2014. Although skin colour has always played a role in immigration regulation, these racist tendencies were concealed behind a facade of liberal decency, except on the fringes of society.

The EU's common asylum policy has only ever been effective in its negative aspects, such as externalisation, push-backs and deportations. Conversely, a common reception policy is not foreseeable, and the distribution of asylum seekers will not work, even with a Common European Asylum System (CEAS). The number of push-backs at EU borders exceeded 120,000 in 2024, including pull-backs by the Libyan coast guard. In 2025, Frontex recorded a 25% decrease in the number of irregular border crossings into the EU, but had to concede that the route across the central Mediterranean continues to be of great significance:

In 2025, the Central Mediterranean remained the most active migration route into the EU, with detection levels broadly in line with 2024. Departures from Libya remained a key factor shaping movements towards Italy.

The Zone of Letting Drown

While the CEAS projects involving external hotspots and FRONTEX-led deportations are a recent development, the zone of drowning has been used as a deterrent since the EU foundation in 1993, albeit with some crocodile tears shed along the way. Monitoring of migration across the sea is carried out by various organisations, including IOM, Frontex and UNHCR. However, the most important sources of information are Alarmphone and Echoes, the magazine of the Civil MRCC (Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre), as well as Caminando Fronteras for theAtlantic route.

Due to pressure from coast guards and conditions in the Maghreb countries, many people have attempted to cross to the Canary Islands in the last two years. According to figures from Caminando Fronteras, 10,475 people died on this route in 2024 and a further 3,090 died in 2025, including 192 women and 437 children. The number of arrivals had fallen by 62% to 17,788 in 2025, meaning that one in six people drowned during the crossing.

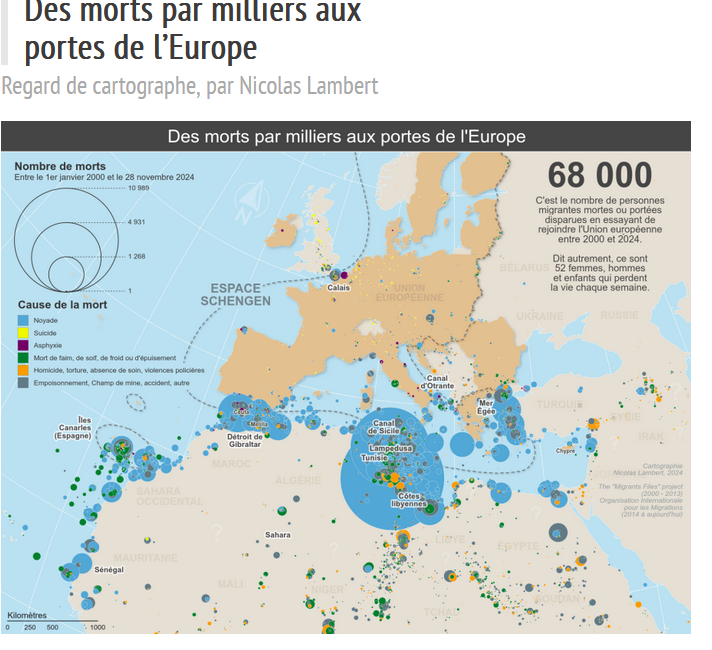

Nicolas Lambert has mapped the 68,000 deaths of people on their way to Europe between 2000 and 2024.

The North African Zone

The Maghreb countries and Egypt make up the second zone of the cordon. Migration-Control.Info and others have thoroughly documented the billions of euros that the EU has paid to the rulers and military regimes in Morocco, Tunisia, Libya and Egypt. Mauritania has also joined the group of proxy border guards, and Senegal has just received millions more for migration control. Coast guards have been financed and equipped in all these countries, except eastern Libya. Several large IGOs, such as UNHCR, IOM, ICMPD, and GIZ are involved in setting up border structures and dealing with "people on the move".

The North African population has not benefited from the European funds. Instead, these funds have been invested in weapons and equipment, or used for the personal benefit of the Moroccan king, the Egyptian military aristocracy, Libyan militia leaders or the Tunisian presidential administration. The situation in the Rif region of Morocco, the Tunisian hinterland and the Nile Delta has continued to deteriorate in recent years, and many potential “harraga” are waiting for their chance. The young people who swim to Ceuta offer a glimpse of what could happen if the regimes in the Maghreb or Egypt were to collapse.

Interception of People on the Move

In 2012, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that rescued at sea in the central Mediterranean could not be returned to Libya. Italy then discontinued its "Mare Nostrum"sea rescue operation. In 2017, a coast guard was established in Libya to return boat people back to Libya (pullbacks). Aerial reconnaissance is carried out by FRONTEX. Italy and the EU have cooperated with the Tunisian coast guard for more than 20 years. A "civilian" sea rescue center is now to be set up in Eastern Libya as well, as quickly as possible.

The actions and abuses of the Libyan coast guard have been well documented. At least the Western Libyan militias have some interest, albeit limited, in the survival of the boat people, whether to extort ransom, sell labour or force women into prostitution. The Tunisian coast guard, on the other hand, has no interest in these people. They are abandoned in the desert. In October 2024 a UN expert stated:

"We have received shocking reports of dangerous manoeuvres when intercepting migrants, refugees and asylum seekers at sea, of physical violence, including beatings, threats to use firearms, removal of engines and fuel, and capsizing of boats."

21,762 interceptions were recorded off the Libyan coast, in 2023. The number of interceptions by the Tunisian coast guard was significantly higher in that year .Morocco claims to have thwarted 78,685 attempts to reach Europe in 2024, with 58% of migrants coming from West Africa. Figures on interceptions by the Egyptian and eastern Libyan coast guards are not available. The Atlantic route has become more important in recent years, but the number of interceptions by the Mauritanian and Senegalese coast guards is unknown.

Racism and "Routes of Torture"

The situation of people on the move in North Africa has deteriorated to the extent that Europe has paid to keep them out. Large sections of the population live in poverty, and nothing has improved since 2011. Racism against Black people is a way of channelling disappointment and rebellion. This racism has existed subliminally for centuries. Now it is flourishing anew, in Morocco, Egypt, Libya, and most of all in Tunisia.[12]

The situation in Tunisia has been documented on this website and in a cartography of violations by Organisation Mondiale Contre le Torture (OMCT), entitled Les Routes de la Torture – The Routes of Torture. In November 2025 Amnesty presented a documentary: "Nobody hears you when you scream". In summary, Melting Pot also reported on the "Invisible Borders of Europe".

Refugees in Libya stated in an interview in September 2024:

According to migrants living in these makeshift camps [in Tunisia, editorial note], more than 80,000 migrants are stranded in these camps (known as kilometres) from km 19 to km 38, and about 1,500 are stranded daily at the Libyan-Tunisian border, and about 2,000 more at the Algerian border, where many face dire conditions, including a lack of food, water and medical care. At least 300 have already died this year after being abandoned in the desert or due to medical negligence in the makeshift camps.

In May 2025, the camps around Sfax were largely cleared and destroyed with bulldozers and excavators. Hundreds were pushed from Tunisia to Libya or deported to Algeria. At the same time, Algeria deported thousands to Niger.

Many people still travel to Libya in search of work, but the security situation is deteriorating and racist attacks are common. This encourages the decision to board a boat to Europe. Hell begins when the boat is intercepted and the people are detained, extorted, tortured or killed. Families in the southern war zones are increasingly impoverished and cannot pay the ransom. Many refugees are sold as labourers; some have been shot and buried in mass graves.[13] Others are deported indiscriminately on a large scale.

Afrique XXI has just published an investigation into prisons in Libya: "A prison system in Europe's shadow", in which thousands are abandoned to their deaths. Meanwhile, there are reports of Italy's plans to build 70 new return centres in Libya.

A migration route from East Libya to Crete has opened up, from which Haftar's army profits in two ways: high fees are collected from migrants, and on the other hand, Haftar has allowed himself to be bribed by Meloni, staging a campaign against Sudanese refugees in the summer of 2025. Refugees in Libya has published several videos about the violence in Tobruk. Hundreds were deported back to the war zone. In December 2025, a meeting between Haftar and EU representatives was reported: the road to Crete could soon be closed again.

In Egypt, the situation for Black migrants has also become very serious, particularly since the war in Sudan began. This has had a particularly severe impact on impoverished refugees. According to a 2024 report, thousands of refugees from Sudan are victims of political persecution or being detained for deportation,: In August 2025, the human rights organisation RPEGY wrote:

These measures [by the Egyptian authorities, editorial remark] include mass arrests, organised and nationwide forced deportations without judicial review and virtually without due process, as well as raids on the homes of refugees or asylum seekers and racist checks during random checks and street raids based on skin colour or neighbourhood. Many of these practices are unprecedented in the history of Egypt, which has been relatively open to refugees until now – especially in terms of their scale and scope.

In Morocco, many Black Africans continue to find shelter in the poorer areas of large cities. However, UNHCR is the subject of protests, as it provides little support for refugees, and travelling onward via Algeria to Tunisia is no longer an attractive option. The atmosphere in northern Morocco is still marked by the Melilla massacre. Black migrants are only tolerated in the southern half of Morocco. The raids in northern Morocco have, in a sense, shifted the colour line to the interior of the country.

Push-backs to War Zones

Along the southern borders of the Maghreb states and Egypt, which extend across the Sahara Desert (excluding the Nile Valley), there has been an increase in pushbacks, with Black migrants being left to fend for themselves in the desert. This southern border corresponds to the trans-African colour line. Until the end of the 19th century, Black Africans were forced to cross this line as slaves. They worked in the oases or were traded as commodities by the Arabs and Ottomans. Following the withdrawal of the colonial powers, this line became blurred as an increasing number of Black migrants crossed it in search of work in Libya or en route to Europe. It is only recently that these borders have been sharply redrawn due to pushbacks and the resurgence of racism.

However, we are speaking of a "line" in a figurative sense. The area is actually a sparsely populated, but permeated by mobility and connectivity, with "villages and crossroads" (Saharan Frontiers, 131). The relationship between the desert peoples and Black migrants would be a topic in itself that we cannot address here. The oases were cultivated by slaves for centuries, and entrenched racism still exists among the Berber and Arab desert populations today.[14] However, the income from the transport business, especially in Agadez, was always welcome.

Algeria deported 31,000 persons to Niger in 2024 and in 2025, Alarmphone Sahara has documented 34.236 deportations. Alarmphone Sahara has been reporting on such deportations for several years (including those from Morocco or Tunisia to Algeria). Many of those deported end up in Agadez, where transport agents have become more ruthless and far more expensive.

Deportations from Libya, involving more than 600 men in December 2024 and 400 men in July 2025, were directly linked to initiatives by the Italian Meloni government. Militias proceeded to expel thousands. Only a few were fortunate enough to be flown to Mali and Chad. Chad repatriated 157 nationals in July 2024 in "partnership with the IOM".

In December 2025, the Libyan authorities stated that

they intend to increase the number of migrant repatriations, particularly in the case of migrants from sub-Saharan African countries. Migrants from Bangladesh are also regularly sent home, and according to the IOM, the number of irregular arrivals is also decreasing.

The Interior Minister explained that the government had been operating what he called a "national repatriation program" since October, and that their goals were to try and return "thousands of migrants" a month to various countries, including Chad, Somalia and Mali. At least two repatriation flights are being planned per week, prioritizing women, children and the elderly, reported AFP.

Trabelsi made clear that Libya does not want to play host to any migrants that are rejected by the EU and it will not act as a third country resettlement spot.

The situation in Egypt has already been mentioned. A report by Sara Creta and Nour Khail (April 2024) documents how thousands of Sudanese refugees are currently being held captive by the Egyptian military and police in secret military bases, awaiting deportation to war in Sudan. Another report by these authors, from December 2025, documents the intensification and expansion of deportation campaigns into cities, as well as the inaction of the UNHCR. These measures are a direct consequence of new asylum legislation demanded and financed by the EU.

Mauritania has recently begun deporting hundreds of Malians across the Senegal River. The raids began shortly after the EU Commission had announced a €210 million migration partnership.[15] The chain of deportations continues in Senegal, to which €30 million of European funds have just recently been allocated for migration control.

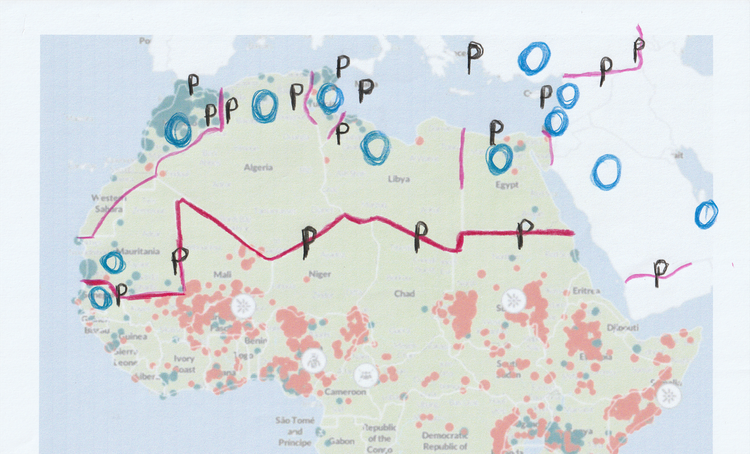

The map is a modification of the ACLED map.

Blue circles: Weapons, training & equipment from the EU, arming of coast guards for border controls

Black Ps: Push backs or pull backs

Small red lines: Fortified borders

Beyond the Colour Line

The result and goal of EU policy is the closure of borders, the drowning of people in the Mediterranean or their disappearance in deserts, the training and equipping of coast and border guards, the payment of militias or governments for pushbacks, pullbacks and deportations. Meanwhile, Europe is in retreat on the other side of the colour line.

Just a few years ago, we criticised the French military presence in the Sahel and MINUSMA, viewing them as a European commitment to stabilising dubious regimes and protecting European interests in raw material, as well as fortifying borders. The military coups in the Sahel (excluding Senegal), beginning in Mali in 2020, were welcomed by many people, particularly in the capital cities. When the new military regime in Niger lifted travel restrictions in Agadez in 2023, this seemed to mark a significant turning point. There was a new peak in the number of people arriving in Lampedusa. However, Europe responded swiftly by offering deals and funding, thereby incentivising the surge in racist violence in Tunisia and Libya, as previously mentioned, and setting in motion a cascade of pushbacks and deportations.

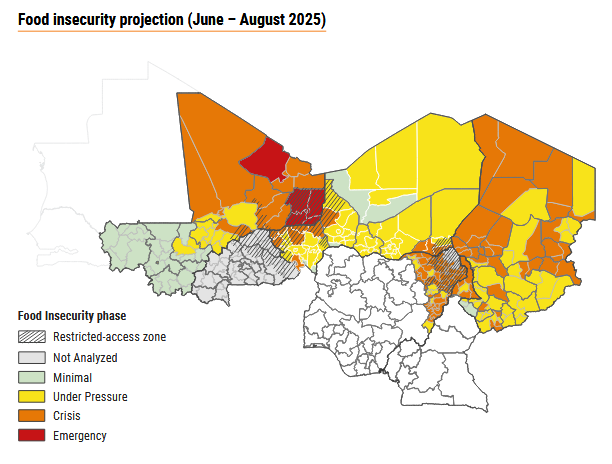

Ultimately, the disintegration of ECOWAS has a negative impact on migration.[16] The routes are blocked by militias and the military, and border restrictions between the coup states and ECOWAS have created new obstacles to migration. In 2025 alone, there were 450 attacks by jihadist militias and more than 1,900 deaths. Bamako is under siege. Four million people, mostly women and children, have been displaced from the war zones. For example, 120,000 of these individuals are currently residing in the Mbera Camp in Mauritania, where the UNHCR has been forced to reduce food rations due to insufficient funding. Others are living in temporary shelters in provincial towns, where they are not receiving assistance. Only one third of the funding for 2025 was secured. However, the rest of the civilian populatio nin the Sahel is also facing increasing uncertainty regarding food supplies.

Sahel: Economy of Chaos, Jihadism & Extractivism

The military regimes in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso have formed an alliance (AES), which has been on the defensive despite cruel military actions over the past year. The troops of France and MINUSMA have been replaced by Russian mercenaries, Turkish drones, Chinese businessmen and Chinese military interests. While European military involvement was subject to critical media and parliamentary scrutiny, the armies and mercenaries can now operate unhindered. Further areas in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger have become war zones. The Washington Post refers to this as "crossroads of conflict":

A belt of chaos stretches across the entire width of Africa, from the Atlantic to the Red Sea. Nowhere else have Islamist extremists seen such astonishing growth since the defeat of Islamic State in the Middle East, with this stretch of land becoming the new epicentre of jihadist activity.

The pastoralists, caught between the desert advancing from the north and state-subsidised agro-industry in the south, are more receptive to jihadist ideologies than the farmers. Their economy, on which more than 20 million people depend, has been severely damaged. The villagers are torn between the jihadists and the army. The army forces tem to dig trenches, after which they are massacred by the jihadists Alternatively, if they side with the jihadists, they are killed by the army, Russian mercenaries and Turkish drones. The survivors are displaced and flee in their hundreds of thousands.

Beneath the military's "anti-colonial" nationalism, a new concept of dispossession and territorial valorisation appears to be emerging, becoming increasingly radical under the pressure of a new debt crisis. Drawing an analogy with the economics of war in Sudan, one could speak of an economy of chaos in the Sahel. Gold is the main source of greed throughout the Sahel region, especially in Mali.

Over the past five years, the price of gold has risen by 75 per cent. [...] In Africa, the gold boom is fuelled by millions of people mining in often illegal mines without safety standards. The main beneficiaries are smugglers, China, Dubai and jihadists. West Africa, and the Sahel region in particular, is experiencing a gold rush reminiscent of the Wild West in the United States.

A main player in the extractivism and land grabbing in Sahel are the Uniter Arab Emirates where all men with suitcases full of gold are welcome. Also the extraction of uranium, oil, rare earths and lithium is being pursued aggressively.

While industrial investments are heavily militarised (Chinese companies operate their own drone stations to protect their investments), up to 2 million men work in artisanal gold mines in Mali alone. In a sense, this offsets the blocked migration to the southern countries of ECOWAS or to the north. In times of blocked migration, the alternatives for young men are the military or jihadism. Many of them would like to migrate to other countries, but all routes are blocked. Jihadism offers them some money, loot and a motorbike.

Achille Mbembe recently published an article in Internazionale entitled Il sovranismo africano che cancella la libertà (African sovereignty that erases freedom), in which he emphasises that "liberation" is based on rebellious youth and coalitions “supported by feminist organisations, civic associations, urban movements and collectives of young people, artists, intellectuals and scientists in search of alternatives”.

Favoured by demographic change, younger generations are now at the centre of public interest: faced with the ageing of power systems, they want to have a say in the continent's development. [...] They are convinced that without democracy and commitment to the community, there will be neither full sovereignty nor full decolonisation.

Mbembe also denounces the trend towards nationalism and militarism:

[This] trend is based on an illusory pan-Africanism and presents itself as the answer to the challenges of a world that is still largely determined by the interests of the major powers. In reality, it is primarily about the logic of power and internal struggles for national resources. Convinced that the balance of power determines the law, the supporters of this trend do not hesitate to support coups and military regimes as long as they are seen as effective bulwarks against neo-colonial and imperialist encroachments. [...] This mixture of coup d'état and sovereignism is taking shape and becoming institutionalised, especially in West Africa and the Sahel. More than in other parts of the continent, the increase in the terrorist threat goes hand in hand with the rise of militarism. The regimes in Mali, Burkina Faso, Guinea and Niger dream, to varying degrees, of establishing "barracks states" in which political, social and economic life is determined by the requirements of a triple war: against terrorism, imperialism and internal enemies.

Reproduction and Mobility

The military is deploying its logic and the struggle for resources in a situation of upheaval in which the reproduction of great parts the population is not yet completely permeated by the cash nexus. French colonialism advanced along the rivers, but developed more of a tributary relationship with farmers and pastoralists. In some ways, their economy is reminiscent of the peasant economy described by Alexander Chayanov, in relation to the Russian village. Migration of the younger generations is an indispensable part of such a reproductive economy. Subsistence, wage labour, and mobility go hand in hand.[17] Theodore Shanin (1971) undertook the task of makinge Chayanov's insights accessible to other regions of the world.

From this perspective, the focus is not on examining the supply of labour to the capitalist cycle, as Claude Meillassoux did 50 years ago. Nor is migration in the Sahel solely a consequence of colonial coercive measures, although forced recruitment and poll taxes played an important role. Post-colonial mobility from rural settlements to cities, to the plantation zones of Senegal, Ivory Coast or Ghana, or further on to Europe, did not simply follow capital's call for cheap labour, but (at the same time) followed a survival strategy of reproductive economy.

Migration has long been a defining feature of Africa’s Sahel region, where historical trade routes, seasonal labor mobility, and transnational kinship networks have shaped patterns of movement. (Minko 2025)

Olaf Bernau (2022, 89 ff.) reports on the importance of mobility and migration in West Africa in a chapter of his interesting book. He emphasises that (rotational) migration is indispensable for life in the villages and for supporting families in an environment of extreme poverty. Two-thirds of the population in the Sahel region live in rural areas, and migration secures their livelihoods and their connection to the cities. By cutting off important migration routes for a few thousand people, Europe is cutting off the path to survival for hundreds of thousands.

Perhaps it will soon be too late to consider the reproductive economy of villages in the Sahel? In the 1990s, there were a number of interesting studies on this topic, some of which focused on the living conditions of women,[18] while others followed the theory of the value of labour.[19] More recently, Camilla Toulmin's book (2020) on the economy of a village in the Ségou region of Mali is particularly noteworthy, as it makes it very clear that these villages cannot survive without migration.

It is not the camel, but the motorbike that is the No. 1 means of transport in the Sahel and the dream of young men. The motorbike promises unprecedented mobility. New forms of protest and a new youth culture could emerge. But the reality is different. Equipped with a motorbike and a water canister, many of the uprooted youths roam across the Sahel in search of work or loot. They fight in northern Nigeria, on Lake Chad, in Libya and currently on the side of the RSF in Sudan. Often they are paid directly with spoils of war. Like many jihadists, these young men often come from the Fulani people, who, at the same time, are increasingly falling victim to military attacks. This example could be used to discuss how the expropriation of livelihoods leads not to uprising, but to looting and warfare.[20]

Through the border cordon, through the colour line, Europe is driving even more young men not only into artisanal gold mines, where their work is reminiscent of the labour of slaves in the oases, but also to the RSF in Sudan and the jihadist militias. In large regions, the jihadists have established themselves as forces of law and order. and providers of income. In many places, they hold court and take a firm stand against capitalist expansion, and one could almost think that they are leading a rebellion against the dispossession of the population. But these fighters oppose any form of emancipation; they are part of a violent implosion behind closed borders. Jihadists need closed spaces to carry out their mischief. Revolts for freedom are inconceivable without freedom of movement.

When discussing anti-racist strategies in times of a new war capitalism and European exclusion policies, we should broaden our horizons beyond the status quo, which includes defending asylum rights and sea rescue operations:

-- We need concepts with which we can defend the de facto right of residence of migrants, even if the legal system of asylum and toleration no longer applies. The last 10 years have made a difference: there are numerous post-migrant structures of self-organisation in Europe to which we can refer more strongly. Again: New York is our beacon.

-- Beyond the Mediterranean, there are important initiatives that oppose Maghreb racism, in Morocco and in Tunisia and Egypt. It is important to support these initiatives to the best of our ability and to cooperate across the Mediterranean. It is also important to promote the freedom of movement of Maghreb youth in the same way as that of sub-Saharan Black migrants.

-- There is an Eurocentrism in the migration debate that we must address. In this context, it would be important to support South-South communication, debates and initiatives there, and to make their arguments and demands heard here in Europe.

-- Perhaps we can succeed in thinking and acting in terms of a transmediterranean reproductive economies in order to link the economy of the diaspora, the economy of metropolitan resistance and the reproductive economies of sub-Saharan populations. At least some spots in Europe could become part of the Black Atlantic!

It is not our problem that Europe is becoming peripheral (or "provincialised"). We do not want Europe to assert itself in the power structure of the new war capitalism. Europe could be a place of diaspora and freedom.

Footnotes

-

Cf. Paul Gilroy (1993): The Black Atlantic, London and New York, Chapter 4

↩ -

Cf. Léon Poloakov (1978): History of Anti-Semitism, Vol. II, Incidentally, the history of Islam with the Jewish diaspora was much more tolerant (cf. Poliakov, Vol. III). When considering the specifics of Western development, this is certainly an interesting point.

↩ -

Without wishing to reopen the long-standing debate on Antisemitism, it should just be noted that it was directed both against Jews as the personification of the indifference of cpaital, and against the subsistence networks of the impoverished population in the diaspora. Both contradicted the political economy of nations and wage labour.

↩ -

Whether the Holocaust can also be classified as "colonial genocide" is an open question. See also Empire, Colony, Genocide (Dirk Moses, 2008).

↩ -

The Nazis' "General Plan East" was about subjugating territories to a war economy and expelling the Jewish and Slavic populations. The plan was accompanied by a theory of "overpopulation" and rationalisation. It provides a backdrop of memes and ideologies, some of which are still influential today.

↩ -

Cf. A. Sivanandan, Liz Fekete (2001), Migration and Racism in the Age of Globalisation, in: Materialien 7, Die Globalisierung des Migrationsregimes, p. 175

↩ -

Germany : Morocco : Niger = 50 : 4 : 1

↩ -

The right to asylum derives from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and was enshrined in the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949. Until the early 1970s, immigration was labour migration, then followed by family reunification. From the end of the 1980s onwards, more and more migrants from the South invoked the right to asylum. This is why the law has been revised in several steps since 1993.

↩ -

Coined by Sven Beckert, this term is, in many respects, a more convincing alternative to "primitive accumulation". One of the strengths of Beckert's new book, Capitalism (2025), is its description of the centuries-long battle between capital and subsistence.

↩ -

Gilroy, Paul (2010): Darker than Blue, Cambridge and London

↩ -

Mbembe, Achille (2002), The New Africans Between Nativism & Cosmopolitanism, In: Geschiere, Peter et al., Readings in Modernity in Africa, London 2008

↩ -

Chouki El Hamel (2014): Black Morocco: A History of Slavery, Race, and Islam (Cambridge); Stephen J. King (2021): Black Arabs and African migrants: between slavery and racism in North Africa, The Journal of North Africa Studies; Arab Reform Initiative (2020 - ongoing): Mobilising against Anti-black Racism in MENA: A Reader; Laura Menin (2024): “Anti-black racism” as a slavery’s afterlife? Sub-Saharan African migrants in the marginalised neighbourhoods of Rabat, Anuac

↩ -

In January 2026, again mass graves were found in Kufra and imprisoned refugees were discovered: see Reuters 15 January 2026 and Devdiscourse 18 January 2026.

↩ -

Stephen J. King (2021): Anti-Black Racism and Slavery in Desert and Non-Desert Zones of North Africa, POMPES

↩ -

More than 300,000 refugees from Mali live in camps in Mauritania; the deportations involved people who were staying in the coastal cities of Nouakchott and Nouadhibou.

↩ -

Minko, Abraham Ename (2025): On Shifting Sands in Africa’s Sahel Region: Tensions between Security and Free Movement, MPI August 20,2025

↩ -

Gijs Kessler (2012): Wage Labor and the Household Economy: A Russian Perspective, 1600–2000 (Brill)

↩ -

Cf. Elke Grawert (Hsg) (1994): Wandern oder Bleiben? Bremer Afrika Studien Bd. 8, LIT (Münster)

↩ -

Bernal, Victoria (1991): Cultivating Workers.Peasants and Capitalism in a Sudanese Village, Columbia University Press

↩ -

In early modern Europe, “war workers” were a constituent part of capitalism, along with military revolution and excessive violence. Peter Way (2009): Class War: Primitive Accumulation, Military Revolution and the British War Worker, in: Marcel van der Linden, Karl Heinz Roth, Beyond Marx, Berlin (Assoziation A), p. 85 ff

↩