Libya

Published August 11th, 2023 - written by: Joschka Dreher, Christian Jakob, Migration Control Redaktion

The article was originally published in German.

Basic Information and Brief Characterization

Libya has the smallest population (ca. 6.8 million) of the states in North Africa,[1] but its huge territory makes it the fourth largest state in Africa. Libya is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt and Sudan to the east, Chad and Niger to the south and Tunisia and Algeria to the west. The capital and largest city in Libya, with a population of around 3 million, is Tripoli. Other important cities are Bengasi, Misrata and Tobruk.

As on the entire African continent, state formation in Libya is an imperial product. The state as it is today, was constructed as an Italian colony encompassing the Ottoman provinces of Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and Fezzan.

The western region of Tripolitania is predominantly populated by Arabs and (arabised) Berbers/Imazighs. Furthermore, the two large refineries (in Zawiyah and Ras Lanuf) are located in this region, and the Mediterranean location benefits high-yield agriculture due to high rainfall. More than half of Libya's total population lives here.

The Tuareg and Tebu have been historically influential in the desert region of Fezzan. The infrastructure is in poor condition, which periodically leads to uprisings and protests. The important oil fields of El Heel and Sharara are located in Fezzan. Historically, the economy in this region is based primarily on trans-Saharan trade, which is undertaken by transnational networks of indigenous minorities.

The eastern region of Cyrenaica is characterized by the contrast of a Mediterranean climate in the north and an arid desert climate in the south. Before the Arab conquests, the region was inhabited by indigenous Imazighen. There are three small oil refineries along the coast. The Kufra oases in the southeast, where many Tubu live, are agriculturally valuable, but their future cultivation is uncertain as they require extensive artificial irrigation. However, there are gigantic freshwater reserves under Libya's territory, which are currently tapped mainly from Egypt.

Economy and Government

After the genocidal colonial reign, and as a result of the Second World War, the UN appointed King Idris (1951-1969) to head the new nation-state. Idris established a strong regime, including banning political parties, expelling political opponents and strictly controlling the press. His successor Muammar al-Gaddafi, who ruled Libya after the military coup of 1969 until his killing in 2011, built his power by delegitimizing state institutions and repressing civil society (e.g. scouts, trade unions and student movements).[2]

Since the revolution in 1969, the Libyan economy has been highly planned with elements such as import bans, price controls and state-controlled distribution. Libya has the largest oil reserves in Africa. The state invested the oil yields on a large scale in public infrastructure, launched housing programs and increased minimum wages. Basic foods, electricity, petrol and gas were subsidized. As a result, Libya was the country with the lowest wealth gap in Africa. The education sector and public healthcare were established, schooling became compulsory from the age of 6 to 15, and school attendance is free.

From the 1990s onwards, the UN sanctions, home-grown economic mismanagement combined with population growth, also due to the recruitment of labor migrant and a (partially) pan-African policy, increasingly led to discontent among the population and resulted in attempts to overthrow the government.[3] During this phase, Gaddafi established a nepotistic network of family members in the state and security apparatus. He pitted tribes against each other and deliberately neglected the Cyrenaica, where King Idris had his conservative base. Through these measures, Gaddafi attempted to mitigate the class struggles caused by the rentier economy between the growing working class and the handpicked upper class, which profited directly from the distribution of oil revenues. Family and descent structures were mobilized, politicized and instrumentalized, for example through clan liability for opposition members.[4] Family loyalties and group-based trust have since played an increasing role.[5] These dynamics still shape the social organization and intensified after the so-called Arabellion. Revolutionary alliances organized along local identities. Acts of revenge erupted between revolutionaries and those loyal to the regime. To this day, family affiliations are gateways to political elite networks. European externalization strategies utilize this social reality. Many projects aim at local ownership: local actors such as militias and ethnic structures are supposed to identify with the measures and internalize the imposed border protection rules and norms.[6]

Nationalism

From the beginning, Gaddafi legitimized his political rule through Libyan-Arab nationalism. At the beginning, this was still under the pan-Arab imprint of Nasserism and the decolonisation movement of the 1950s and 1960s. With time, an more and more exclusive definition of belonging as a purely Arab one gained importance.[7] According to this notion of belonging, only Arabs, women married to an Arab and only individuals under the age of 50 can obtain citizenship. The division into an Arab self versus the non-Arab other functions as a strategic means of constructing a racist Arab social system.[8]

The Arabellion

The initial spark of the Arabellion was the self-immolation of the vegetable vendor Mohamed Bouazizi on December 17th 2010 in Tunisia due to his devastating economic circumstances. By early 2011, Libya saw first mass protests, waves of arrests and state killings, as well as the shutting down of the internet.[9] The protesters demanded "bread, freedom and social justice". Gaddafi met with four lawyers, among them Abdul Hakim Ghoga, the president of the bar association, who played an important role in the uprising, first as spokesperson for the National Transitional Council, then as its vice president. In response to their far-reaching demands for freedom of the press and freedom of expression, housing and education, as well as a voice, he replied: "All that the people need is food and drink."[10] A few days later, the opposition called for the "Day of Rage", during which protests took place across Libya and many brave people lost their lives.

On March 17th 2011, the UN Security Council established a no-flight zone and NATO began its military campaign against Gaddafi. Now the tide turned in favor of the opposition. On October 20th 2011, Gaddafi was assassinated and his body defiled.

Disintegration and War of the Militias

Although the first free election of the Libyan National Congress took place in 2012, the political and territorial power structures differentiated and fragmented from 2014 at the latest. This resulted in open wars in 2014 and 2019. The majority of the parliament and the government-in-exile under Abdallah al-Thinni established their new power base in 2014, supported by the self-proclaimed General Chalifa Haftar,[11] in the eastern Libyan city of Tobruk and installed the "House of Representatives (HoR)" in Al-Baida. In Tripoli, another government, the Government of National Accord (GNA), was formed in 2016 under the leadership of Fayiz as-Saraj. This power faction also included part of the National Congress and various militias from Misrata. In early 2021, after the resignation of as-Saraj, a new transitional government was formed under UN mediation, with the businessman Abdul Hamid Dbaiba appointed as its prime minister. Internationally, the alliance in Tripoli is portrayed as Islamist because of its proximity to the Muslim Brotherhood, in contrast, the alliance that dominates the east is portrayed as anti-Islamist. However, both sides reject this external ideological categorization and the alliances are predominantly based on balancing different interests through participation in power and funds.[12]

European Interests

The direct or indirect European interventions in the Libyan conflict each pursue their own geopolitical and economic interests. While Italy supports the supposedly Islamist government in Tripoli, France backs the allegedly anti-Islamist Haftar. In spring 2020, Haftar's troops reached Tripoli, supported by the Egyptian air force and the Russian "Wagner Group". A massive Turkish intervention pushed them back from the region in April 2020. All these countries are competing for influence and access to Libya's oil reserves.[13] Both sides are supported by numerous militias, but none of the rival governments can access the national budget or the divided central bank. Thus, the militias and warlords either seek support from neighboring states or find other sources of income (smuggling oil, weapons and migrants, drug cartels, kidnapping and extortion).[14] Those militias that did not have a direct military presence in Tripoli after 2011 occupy oil infrastructures to gain political bargaining chips.[15] The "Anger of Fezzan Movement" is a social movement broadly supported by the local population and democratically legitimized. It occupied the Sharara oil field in 2019, demanding fundamental changes in the historically disadvantaged region in the south: e.g. infrastructure, health care, water access, regional development.

The EU and the Berlin Process

While Italy, France and Turkey have for the most part pursued their own geostrategic and economic interests (and those of the oil companies INI and Total, respectively), Germany pledged to safeguard the interests of the EU as a whole. In June 2021, the second round of the Berlin Conference on Libya was held. Officially, the German government wanted to support the peace negotiations in Libya with the Berlin Process. However, it is first and foremost part of the European border and migration policy. After all, only a stable Libya can keep all the migrants in the country. The widespread war crimes and crimes against humanity in Libyan prison camps committed by militias that are largely financed by the EU and the German government show how insignificant self-commitments are for Germany and the EU.[16] The final declaration of the second Berlin Conference on Libya calls for "peace and prosperity for all Libyans", however, indigenous minorities, de jure and/or de facto stateless persons and people on the move are excluded.

Six months and another Libya conference later - in Paris in November 2021 - it is clear that the situation in Libya has not changed. France is still pursuing its own interests. The presidential elections of December 24th 2021 were boycotted and postponed by the elites,[17] the Turkish and Russian military units[18] have not been withdrawn, the militias and the so-called Libyan coast guard continue to operate, and thousands of refugees protested in the streets before being transported back to the detention centers by brute force.[19]

Migration Movements

Libya remains one of the crucial countries along the central Mediterranean route. In 2016, a few months after the peak of the long summer of migration, 181,000 people reached Italian territory from Libya. That was 90% of all registered crossings to Italy,[20] on the deadliest route in the world. Therefore, Libya has become a focus of European foreign and security policy. Since then, the number of people arriving via the central Mediterranean route has fallen dramatically. The reason for this are the externalization strategies of extra-territorialisation, privatization and technologisation/militarisation[21] - but above all also the "European solution" of letting people drown, which reached a sad peak once again at Christmas 2021. State-run maritime rescue missions have been discontinued and simultaneously the actions of private rescue ships are being systematically obstructed and their crews criminalized. Today, "rescue" mostly means the pull-back of refugees to Libya and internment by EU-supported and trained Libyan coastguards or militias.[22]

Mixed Migration: Regional and Local Perspectives

Most migrants in Libya originally did not plan to cross the Mediterranean on rubber boats. Indeed, Libya is not just a transit country on the way to Europe, as the common EU narrative frames it, but has been a destination country for up to 1 million labor migrants. The dramatic deterioration of the situation in Libya has forced them to flee across the Mediterranean. As a sparsely populated and oil-rich country, Libya offered relatively well-paid work until a few years ago. In the course of the oil price crisis, many people migrated for work from Tunisia and Egypt from 1973 onwards.[23] Later, people from sub-Saharan and East Africa as well as West Asia and North Africa also came to the oil-rich country in search of economic prospects, work and social security.[24] In September and October 2000, pogroms against migrant workers in Libya took place in Tripoli and the surrounding area: 130 to 500 black Africans were beaten to death. To escape the hounding, thousands of construction and factory workers from Niger, Mali, Nigeria and Ghana fled south. Many of them got stuck at road controls in the Sahara and ended up in Libyan military camps. In this context, "Le Monde Diplomatique" reports on a number of detention centers where migrants and refugees have been interned since 1996.[25] Parallel to Libya's rapprochement with the EU, labor migrants have been increasingly criminalized and detained following the introduction of a range of visa regulations. In the most recent surveys, migrants came from Niger (20%) and Egypt (18%), followed by Chad (15%), Sudan (15%) and Nigeria (6%).[26]

Statelessness as a Means of Political Rule

While in power, Gaddafi exploited the right of citizenship as part of his rule. This created contradictory and precarious residence situations, especially for immigrants, and continues to shape who is considered Libyan or non-Libyan to this day. Indigenous minorities, who live predominantly nomadically, also barely had access to naturalization documents. In the 1970s and 1990s, Gaddafi exploited the resulting lack of prospects and recruited his militias among the indigenous and migrant population in exchange for a prospect of naturalization. In 2010, Arabs who had immigrated since the 1980s and those returning from exile were suddenly declared stateless. The principle of descent in the respective laws in particular discriminates against women, as citizenship is passed on from the father's side. Non-Libyan women are granted citizenship through marriage, if they discard their former citizenship. Overall people are being naturalized based on their usefulness in terms of labor politics.

Migrants and Refugees

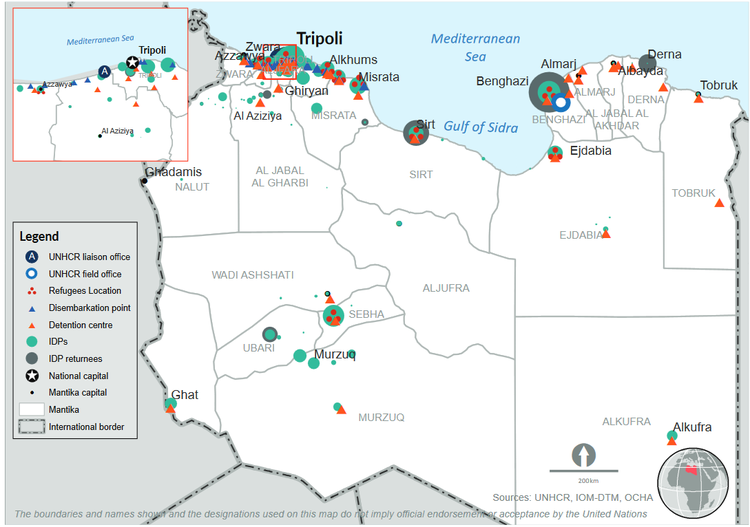

As numerous as the countries of origin of the people in Libya are, as manifold are their reasons for fleeing and migrating: droughts and climate catastrophes, terrorism and political instability, exploitation in neo-colonial power relations, youth unemployment and fears for the future, but also the search for a better life. In Libya, economic, political and ecological causes and motives for migration culminate.[27] In March 2021, the IOM registered 571,464 migrants, 278,177 internally displaced people and 604,965 supposedly voluntarily repatriated persons. UNHCR recorded 43,624 registered refugees and asylum-seekers in the same month. Thousands of migrants are interned in official or informal detentions centers run by militias: the estimate of 3,934 made by UNHCR for February 2021 is far too low. In all this, the geographical distribution is highly uneven: The West is home to 53% of all people on the move, while the other half is distributed 29% in the East and 18% in the South. Urban strongholds are Tripoli, Ejfabia and Misrata.[28]

The living conditions of vulnerable people are extremely precarious. This applies to the working conditions of migrants, insofar they have not been detained, and even more so to people in the detention centers. In 2017, video footage of a slave auction in Libya gained international attention. The Xchange report from 2017, the reports by Sally Hayden and Ian Urbina and the documentary by Sara Creta disclose the detention system in Libya, which is funded by and thus in the responsibility of the EU.

EU Projects

The EU shapes the border and migration policy in Libya significantly in line with its interests. This influence started in the early 2000s and was further consolidated with the "New EU Pact on Migration and Asylum" in 2020. The EU is implementing a variety of programs in Libya based on multilateral, bilateral, military and humanitarian agreements and initiatives. These projects blend humanitarian aid and so-called migration management. Humanitarian actors thus become part of, if not a driving force behind, the outsourcing of European border and migration policy to Libya. In addition to humanitarian actors, EU member states and the EU cooperate with various Libyan actors to implement their migration policy - including militias that have been involved in war crimes. However, the "New EU Pact on Migration and Asylum" also shows that the EU hoped for comprehensive cooperation on migration and border issues with the new Libyan government and sought to give its actions a legal appearance. After the elections scheduled for 24 December 2021 have been postponed, this goal is receding into the distance. The desired cooperation at the highest government level could have been based on existing programs and projects. Until consolidation, the EU will probably continue to cooperate with those actors with whom the EU's interests can best be implemented.

Bilateral Agreements

The outsourcing of the European border and migration regime is also facilitated through bilateral agreements. Annex 2 provides an overview of the bilateral cooperation on migration. The cooperation between Libya and Italy is especially noteworthy; reflecting the importance of the central Mediterranean route between the two countries. The friendship treaty that Libya concluded with the former colonial power Italy in 2008, led to a close cooperation on migration related issues. The treaty is an attempt of the Italian government to establish itself as a partner, also by paying reparations amounting to 5 billion euros. However, the core of the treaty was to push bilateral efforts on migration control. It established a legal framework that enabled the Italian coast guard to hand over people it intercepts on the high seas to the so-called Libyan coast guard without checking their legal status.[29]

Another landmark agreement was signed by Libya and Italy in 2017. The agreement on the "containment" of migration stipulates the provision of funds for detention centers and the training, equipment and financing of the so-called Libyan coast guard. The members of this so-called coast guard are recruited from militias and carry out illegal pull-backs in the Mediterranean, in cooperation with Frontex reconnaissance aircraft. Indigenous actors are controlling the central routes in the south and in the desert regions. Some of those Indigenous groups have been border guards since colonial times and are regionally well connected.[30] The Italian-Libyan agreement was extended for another 3 years in February 2020.

European Union Border Assistance Mission (EUBAM) in Libya

In order to implement its migration-policy interests in Libya, not only Italy, but the entire EU cooperates with militias. Such cooperation takes place, among others, through the "EU Integrated Border Assistance Mission in Libya" (EUBAM Libya). EUBAM is a civilian mission to support the control of Libya's land, sea and air borders. It was decided by the European Union in 2013 within the framework of the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). The mandate, which has been extended until 2023, includes support for the Libyan authorities in the area of border management and internal security. The core of EUBAM is the training of Libyan police, border guards and customs - and with it the training of members of Libyan militias. In addition, EUBAM aims to develop so-called "Integrated Border Management" (IBM). The "New EU Pact on Migration and Asylum" reaffirms EUBAM's role in strengthening Libya's borders, allocating it a budget of 85 million euros for the period 2021-2023.

Politics in the Central Mediterranean

The EU is paying particular attention to the Mediterranean Sea. In June 2015, the EU launched a military operation called EUNAVFOR MED (European Union Naval Force - Mediterranean) to fight so-called traffickers in the central Mediterranean. Initially, this operation was supposed to also take action against the traffickers on Libyan territory. This failed due to opposition from both the Libyan parliament in Tobruk and the Libyan central government under Prime Minister Fayiz as-Sarraj. The mission Operation SOPHIA, which was renamed EUNAVFOR MED in October 2015, was therefore limited to training the so-called Libyan coast guard. Since 2016, Frontex has been involved in this training.Part of the SOPHIA mission also included patrols outside Libyan territorial waters, which boarded several thousand people in distress at sea. Within the EU, their fate became an ongoing dispute. Some states feared the operation would attract more refugees. As of April 2019, the EU therefore no longer deployed its own ships, but limited itself to training the so-called Libyan coast guard. Operation SOPHIA was discontinued at the end of March 2020.

On 31 March 2020, the military operation IRINI was launched to enforce the UN arms embargo against Libya. Today, "capacity building" and training of the so-called Libyan Coast Guard are again among its tasks. Frontex continues to participate in these trainings. Moreover, in 2018 Libya was linked to the border surveillance system EUROSUR, which runs under the auspices of Frontex. Using drones, reconnaissance equipment, offshore sensors and high-resolution cameras, it mainly monitors the airspace over the Mediterranean Sea. Libya received a "tailor-made software application". In addition, Frontex supplies data informally to the so-called Libyan coast guard via Whatsapp. The practice has been heavily criticized. At least eight reported cases of pull-backs from the Maltese search and rescue zone to Libya, a Frontex aircraft was circulating near the boats. But even before these documented incidents, Alarmphone, Sea-Watch, Borderline Europe and Mediterranea published a report accusing Frontex of being complicit in pushing tens of thousands of people on the move back to Libya based on their aerial surveillance. "EU actors have thus become accomplices in serious human rights violations", the report "Crimes of the European Border and Coast Guard Agency Frontex in the Central Mediterranean Sea" states. This complicity will increase. The "New EU Pact on Migration and Asylum" emphasizes, that the EU wants to continue to strengthen the so-called Libyan Coast Guard and the "General Administration for Coastal Security" (GACS) through training and equipment - most recently by donating new surveillance technology.

Funding

The funding of these and other migration policy projects of the EU and individual EU member states is opaque. Multiple funds finance numerous programs and actors that implement these programs and policies. However, since it is often not well documented, the funding as well as the implementation of outsourcing politics remain intransparent.

One important financial instrument is the European Union Emergency Trust Funds for Africa (EUTF). This fund, established in 2015, finances a range of for-profit and non-profit actors operating in Libya, but also in other African states - be they IOs or the so-called Libyan Coast Guard.

List of the EUTF partners in Libya

The list of international or governmental organizations working in Libya on behalf of the EU and paid from the EUTF can be found on an official website of the European Commission. We also refer to the projects in Annex 1. The programs deal with the management of "mixed migration flows" or "protection and sustainable solutions for migrants and refugees". Funds for migration management, financed with 90 million euros since 2017, are shared by UNDP, UNHCR, UNICEF, IOM and GIZ. "Protection and sustainable solutions for migrants and refugees" is financed with 115 million euros and implemented jointly by UNHCR and IOM.

The major project partners funded by the EUTF:

- UNHCR: 16 projects;

- IOM: 15 projects;

- UNICEF 7 projects;

- UNDP 4 projects;

- Italian Ministry of the Interior: 3 projects (Equipping the so-called coast guard and “pilot projects” at the southern border);

- Agenzia italiana per la cooperazione allo sviluppo, Danish Refugee Council, GIZ, IRC, IRCWater and Sanitation Center, Global Initiative against Transnational Organizes Crime und UNPF: each 2 projects;

- Altai Consulting, CEVESI, ICMPD, International Medical Corps, Italian Development Corp., SNV Netherlands Development Org. and UN Capital Development Funds: each 1 project.

The "New EU Pact on Migration and Asylum" also relies on other funding instruments in addition to the EUTF. For example, the new "Multi-country migration programme for the Southern Neighbourhood" provides a more flexible financing of migration control in Libya between 2021 and 2027. Furthermore, the Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI) is used to fund the so-called fight against smugglers, which includes monitoring as well as trainings for the Libyan judiciary and prosecution. Other EU instruments include the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF) and the Border Management and Visa Instrument (BMVI). It is also proposed to introduce the Team Europe Initiative (TEI) as an additional funding mechanism for border externalization programs to Libya. Without this indirect and flexible funding, the EU would not be able to interfere with the different levels of power in Libya – as officially, it only supports the internationally recognised government in Tripoli.

What is the role (of which) IOs and NGOs?

International organizations (IOs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) assume a central role in the externalization of the European border and migration regime to Libya. Funded by the EU, they implement the policy of externalization and at the same time give it a humanitarian veneer. Therein, IOs and NGOs compete for the financial favor of the EU. Many IOs, such as the IOM, finance their operations on a project basis. The projects need not only meet the political requirements of the donors, but their results must also be quantifiable and correspond to a supply-oriented service. In the "Technical Coordination Groups", which meet regularly, the project partners have to account for their activities to the EU delegation. The more effective and transparent the programs are, the more respected and legitimate they are in the eyes of the donor countries. And the more likely IOM, ICMPD or private providers like Altay Consulting are to secure lucrative contracts and access a variety of funding mechanisms. Even if no congruent overview of the operations of IOs and NGOs exists, their predicament to either engage in the dirty business of externalization or forfeit access to funds is undoubtedly discernible. This often leads to a two-faced game. While the IOM laments the deaths in the Mediterranean on the one hand,it has been functioning as a service provider for camps and migration management for more than 30 years on the other hand. This is similar to the function of the ICMPD, a pacemaker of externalization, which masquerades as a research institution. But things are not much better for UNHCR and other venerable IGOs and NGOs that have become partners of the EUTF.

The role of international as well as national NGOs in Libya, is discussed in the blog post on migration-control.info by Paolo Cuttitta. The author describes the role of NGOs in Libya, in an area of tension between "externalized and humanitarian space":

«Since 2011, the Libyan context has changed radically. In the last ten years, about twenty larger and smaller INGOs have been active in migration-related projects alone. They often work on behalf of international organizations (IOs), such as the UNHCR, or run their own projects funded by individual governments or the EU. With the intensification of the political and security crisis in 2014, the Libyan representations of INGOs moved their headquarters to Tunis. Remote coordination is one of the many problems that make it difficult to implement projects in Libya, a country at civil war, and one of the reasons why some INGOs entrust local NGOs with project implementation.

To date, a few hundred Libyan NGOs are active in Libya in various fields, including migration. Officially, around 5,000 NGOs are registered, but most are inactive. Many smaller NGOs work on a voluntary basis, with little to no donor support. Others operate mostly as implementing partners of IOs and INGOs and live off their contracts. Some have grown into large firms. According to representatives of other NGOs, for example, the main partner of the International Organization for Migration (IOM) is „not an authentic expression of civil society“ but „an enterprise“ that is „ready for anything“.

[…]

With the sole exception of MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières), whose projects are only made possible by private donations, all INGOs working on migration in Libya are directly or indirectly funded by government money (from states, from the EU, etc.). This raises the question of the relationship between humanitarian and externalized space.”

The role of UNHCR in Libya

This intertwining of humanitarian and externalized space is also illustrated by the UNHCR and its Libya programs. The role of the UNHCR is anything but simple. Dorothée Krämer analyzes the situation on our blog:

«When states are unable or unwilling to protect refugees, the agency tries to fill the void by providing direct assistance to people under its mandate. […] In the spirit of bureaucratisation, people have to register with the UNHCR as asylum seekers in order to receive basic support services. Yet registration does little to help people. The certificate they receive as asylum seekers from the UNHCR is not recognised by the Libyan authorities. Accordingly, it does not protect them from arrest and detention. Many of those who are in the camps are registered with the UNHCR. […]

The UNHCR has extremely limited access to the detention camps, usually only through partner organizations. The IOM and the UNHCR are often on the ground at the port when intercepted people are brought back by the so-called Libyan Coast Guard. They can try to save lives, provide some water and food, and register people – but they cannot prevent them from being taken to the camps. Nor can the UNHCR provide safe accommodation for those who have escaped the camps. […] All that is left for the UNHCR to do is to regularly call for the liberation of all people held in the camps and for the EU to increase quotas for humanitarian visas and to link support for Libyan authorities to their compliance with human rights. But the European Union ignores these words without batting an eyelid.»

Evacuation Programs

The intertwining of humanitarianism and migration control can further be seen in evacuation programs. These programs sometimes function to refute the accusation that the EU's migration and border policies lead to the martyrdom of thousands of people in Libyan detention centers - even more, that this martyrdom is a building block of the EU's migration defense.

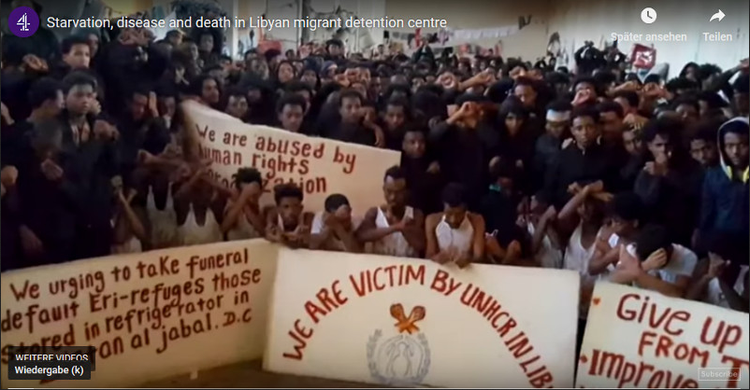

The conditions in the Libyan detention centres are well known: Torture, extortion, rape and slavery prevail. Human rights organisations such as Amnesty International have been accusing the EU of being largely responsible for this: "Fresh evidence of harrowing violations, including sexual violence, against men, women and children intercepted while crossing the Mediterranean Sea and forcibly returned to detention centres in Libya, highlights the horrifying consequences of Europe’s ongoing cooperation with Libya on migration and border control," reads an Amnesty report from July 2021. The EU is seeking to rebut this accusation with two programs. This means that the EU grants funding to the UN agencies IOM and UNHCR to bring some of the detainees out of captivity. But getting them out of the detention centers is much more difficult than making sure they get in.

Voluntary Assisted Return (IOM)

People on the move, including detainees in Libyan detention centers, are classified by UN institutions into two categories: People with potential refugee status and migrants. The latter are assumed to be able to return to their country of origin. For this group, the UN migration agency IOM runs the Voluntary Humanitarian Return Programme (VHR). Between 2017 and February 2020, IOM flew more than 50,000 migrants out of Libya to over 44 countries of origin at EU expense. IOM charters planes and accompanies the migrants. IOM claims that those “returned” are met by IOM staff in their countries of origin and receive assistance, including transport allowances and temporary accommodation. According to IOM data, the returnees are entitled to 1,500 euros in reintegration assistance to help them re-establish themselves economically. This is usually considerably less than the people spent on the trip to Libya, which is why they are often highly indebted. Furthermore, the claimed voluntary nature of such a return is more than questionable.

Emergency Transit Mechanism (UNHCR)

People on the move from countries that are not so-called safe countries are potentially classified as refugees. This applies for nationals from Eritrea, Sudan, Palestine, Ethiopia, Iraq or Afghanistan, for example. UNHCR is responsible for them. UNHCR runs the Emergency Transit Mechanism (ETM) program in Libya, which is also funded by the EU: evacuation flights for captured refugees from Libya who are to be taken to safe places. But not many states are willing to take them in.

The first evacuation flight took place on 11 November 2017. In the initial phase of the project, several hundred people were flown to European countries via the ETM. In 2019, Rwanda has also agreed to take in a few hundred refugees from Libya through the ETM project. However, most of the evacuees have been taken to Niger. In order to make a selection, the category of "special protection needs" is applied. Especially victims of torture, pregnant women, girls, women, minors or sick people are categorized as such. On this basis, UNHCR draws up the lists for evacuation. But even for those who are considered "particularly in need of protection", there are not enough places in the ETM program, which is why most of them remain in Libya. This program serves the EU to a large extent to conceal its own role: after all, it pays the so-called Libyan coast guard, who take the people to the detention centers from which UNHCR then claims to free them.

Who Benefits?

Numerous actors are profiting from the outsourcing of the European migration and border regime to Libya. A comprehensive overview of the profiteers has yet to be compiled. Besides the political and economic profit of the EU and companies involved in the border business, militias also profit from oil and arms smuggling as well as from the refugee business. Their trading partner in the oil business is the Italian mafia, partly via Malta as a stopover. Howeber, since the devaluation of the Libyan dinar, oil smuggling has become less attractive. This also leads to people on the move being coerced now even harder than before.

The militias earn money from the people on the move business both by herding people onto the overcrowded boats and by extorting payments in the detention centers. Both the militias of the so-called Libyan coast guard and the central administrators collect money from the EU. Militias on the southern border also receive payments from the EU to control the borders. Migrants who are not interned and who have to work for pittance benefit the informal sector of the economy, especially construction, agriculture and households.

The European externalization policy also benefits the European, Turkish and Russian security and arms industries. Several states are vying for influence and access to the oil wells. And last but not least, the humanitarian organizations that implement this policy in Libya also benefit.

IOs and NGOs

With the humanitarization of borders, so-called humanitarian actors become profiteers of the outsourcing of borders as well. Organizations such as UNHCR, IOM, but also UNICEF, the Danish Refugee Council and GIZ implement European border policies in Libya, financed through instruments such as the EUTF.

For more on this, see section What is the role (of which) IOs and NGOs?

Private Security Firms

Private security companies and the arms industry are also interested in the increasing outsourcing of European border control. It opens up a new sales market. In order to maintain and even expand this market, the arms industry is lobbying. Private security companies are often involved in migration-specific risk analyses in which they themselves identify the need for their arms products. The outsourcing of the border regime to Libya began with the lifting of the weapon embargo to Libya in 2004, which resulted in the involvement of the private security and arms industry. It was followed by arms sales by French, British, German, Maltese and Russian private security companies. The Italian Finmeccanica and its subsidiaries Alenia Aeronautica and SELEX Galileo are among the biggest profiteers. But companies like BAE Systems, Thales and Airbus, Boeing and HP also have signed contracts to profit from border control in Libya. However, these profits of the arms industry are only possible through investments by investment firms, banks and states, as Martin Lemberg-Pedersen points out in a study.

Libyan Economy

The Manifesto of the self-organized movement “Refugees in Libya” elaborates, the significant, yet invisible role of refugees in the Libyan economy:

“Here we became the hidden workforce of the Libyan economy: we lay bricks and build Libyan houses, we repair and wash Libyan cars, we cultivate and plant fruit and vegetables for Libyan farmers and Libyan dining tables, we mount satellites on high roofs for the Libyan screens etc.”

With the criminalisation and thus disenfranchisement of people on the move in Libya, many people find themselves in highly vulnerable situations, since they barely have legal possibilities to protect and defend themselves against exploitation. This is exacerbated by the fact that the European border policies restrict the possibilities to escape the country. The prices for onward travel or flight are continuously rising, which makes people dependent on work, no matter how exploitative it is.

The Militias

Another consequence of the criminalisation of migration in Libya is arbitrary arrests and detention. People on the move are held in official and unofficial detention centers, some of which are run by militias. Funded by EU money and whitewashed by EU programs, these detention centers are a lucrative business for militias. Detainees have to buy their freedom, are sold to other detention centers or into slavery - sometimes at slave auctions. In the detention centers, detainees are sometimes coerced into forced labor. For example, fugitives in the Tajura center east of Tripoli report having had to clean the weapons of the Zintan brigade, to store their ammunition and unload military transports. The detention facilities are not the only source of profit for Libyan militias. They also receive money from European funds and donations of technology and military equipment in their function as the so-called Libyan Coast Guard.

Who is Losing?

With the criminalization of migration in Libya and with the increasingly sealed borders due to the militarization of border guards and the so-called Libyan Coast Guard, People on the Move are stuck in Libya - as illegalized. This illegalisation pushes people into exploitative conditions, which is further fuelled by widespread racism. Migrants are being locked up in detention centers in Libya under untenable conditions, - regardless of whether Libya is a transit country or their destination. However, it is not only migrant workers and people on the move in Libya, who are affected by the cruel consequences of European externalization policies. Their families are also impacted, as the anticipated remittances fail to arrive and many households have to come up with extortion money for the militias from afar.

Finally, the everyday violence in the militia war, which has been going on for ten years, is further fuelled by the military build-up of the violent actors, which has an impact on Libyan civil society - and further exacerbates racist and patriarchal oppression.

What Resistance Is There?

Self-organized Protest and Autonomy of Migration

Both the context of violence in Libya and the brutality and arbitrariness of local militias and gangs stifle migrant self-organization. Black people and people of colour are particularly affected by torture, racist discrimination and collective disenfranchisement. Nevertheless, there is still resistance. Like any resistance of marginalized minorities, migrant resistance is characterized by self-organized and spontaneous protests. But resistance does not only take the form of open protests: Refugees and migrants are acting subjects who react subversively and willfully to the manifold conditions and obstacles, and challenge them again and again. While the EU and its member states are raising their border fences or externalizing them further, migrants are seeking new - and often more dangerous - routes. For example, since 2020, migratory movements have shifted to Tunisia and toward the Canary Islands.

Protest Against The Camps

During the work on this article, up to 3000 people demonstrated daily in front of a UNHCR building in Tripoli. They were there for weeks, chanting and holding banners in four different languages. With Twitter (@RefugeesinLibya) and Facebook accounts (@refugeesinlibya) as well as a website (https://www.refugeesinlibya.org/), they have built up their own communication channels through which they try to reach the attention of the international public. Their demands remain: The liberation of all refugees held in the detention centers, as well as safe accommodation and evacuation from Libya as soon as possible. They condemn the European Union's support of the so-called Libyan coast guard, the system of detention centers as well as the inaction of the international community, including the African Union. They are particularly harsh in their criticism of the UNHCR, the organization whose mandate it is to protect them - and which, instead of backing them, is now scapegoating the protesters. In the meantime, the protest camp has been forcibly dispersed and the protesters transported to the detention centers. But this protest, the largest of its kind in many years, will have long-lasting effects.

Protest in front of the UNHCR Day Center, Tripoli, Januar 2022 (C) @RefugeesInLibya

This protest was not the first of its kind in Libya. In recent years, refugees have repeatedly organized themselves to fight their desperate situation. When the UNHCR wanted to close the Choucha detention center in Tunisia on the Tunisian-Libyan border in June 2013, the 650 or so people still living there reacted with hunger strikes and protest detention center. In September 2018, detained people, mainly from Eritrea and Ethiopia, protested to open the detention center in Qasr Ben Ghashir, on the southern outskirts of Tripoli. Their subsequent protest march led them towards Tripoli, 20 kilometers away. They also took to social media to denounce the inhumane conditions in the detention centers and demanded immediate assistance and evacuation by UNHCR. In February 2019, out of fear and desperation, similar protests were held in the Sikka detention center (near Sabha), but were bloodily crushed by Libyan security forces. Fifty people were injured. In June, there were again protests, mainly by Eritrean refugees, this time in the Zintan detention center, where 22 people had died in the six months prior.

The detainees demonstrated, hands crossed into fists above their heads tilted to the ground. On posters they had written in tomato sauce: "Why does the UNHCR ignore our tears in Libya?” In the space in front of them, where they spent their days and nights, there was a huge pile of rubbish around which flies were flying. After 53 detainees were killed in an airstrike on Tajoura dentention center in July 2019, UNHCR evacuated only 55 of the remaining 360 people from the center, which caused a hunger strike. The survivors refused to return to the detention center. One of the survivors summed it up like this: "We don't need food. The only solution is to get us out of here. We need evacuation to a safe place." 350 people were eventually released. They sought shelter at a UNHCR facility that temporarily housed those of the extremely vulnerable refugees selected by UNHCR for evacuation programs. Initially, UNHCR provided shelter for new arrivals, but as more and more people arrived and the security situation deteriorated dramatically due to the prevailing civil war, the facility was closed.

Annex 1:

Existing EU cooperation and areas of engagement under the New Pact

(Source: https://migration-control.info/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Libya.pdf)

I. Protection

EU action focuses on protecting migrants, refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs) while supporting social cohesion and vulnerable local communities. Protection support provided under the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa includes facilitating access to basic services, assistance and protection to vulnerable migrants, fostering shelter and alternatives to detention, and ensuring protection monitoring notably through improving conditions for migrants and refugees at disembarkation points and in detention centres as well as in urban areas with multi sector assistance services, and providing employment opportunities and resilience at community level.

Concrete projects under the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa include:

- Strengthening protection and resilience of displaced populations in Libya - DRC, CESVI, IRC, IMC - €6.9 million

- Managing mixed migrations flows in Libya through expanding protection space and supporting local socio-economic development' protection pillar - IOM, UNHCR, WHO - € 99.6 million (overall programme € 178.2 million)

- Integrated approach to protection and emergency assistance to vulnerable and stranded migrants in Libya’ - IOM, UNHCR - € 29 million

- Durable solutions for Refugee Unaccompanied and Separated Children and Family Reunification – UNHCR - € 800 000

- Protecting most vulnerable populations from the COVID-19 pandemic in Libya - WHO, IOM and UNICEF - € 20 million

- PEERS: Protection Enabling Environment and Resilience Services – addressing protection, GBV assistance, host families in Misrata medical assistance, community-based health-care targeting migrants and refugees - CESVI/IMC - € 5 million

- Regional Development and Protection Programme II (development pillar) – in case of Libya, focusing on Labour Mobility and Human Development, to strengthen labour migration governance in Libya – IOM € 8 million

- Regional Development and Protection Program III (development pillar) – in case of Libya, reinforcing inclusive services and fostering social cohesion and employment opportunities – Norwegian Refugee Council, INTERSOS, ACTED, IMPACT, Danish Refugee Council, International Rescue Committee - € 6 million

- Regional Development and Protection Programme in North Africa (RDPP), protection pillar, co-funded under the EU budget and managed by the Italian Ministry of the Interior (2020/2021):

- Refugee status determination, resettlement and direct assistance - UNHCR - €630 000

- Direct assistance to vulnerable migrants in Libya - IOM - €900 000

- Protection and health for refugees, asylum-seekers and migrants in Libya - CEFA - €900 000.

II. Humanitarian evacuations, voluntary humanitarian return of vulnerable migrants to countries of origin and the sustainable reintegration of returnees

The main objective of EU support in this area is to strengthen migration governance in the region and provide protection and sustainable solutions for migrants and refugees along the Central Mediterranean route. This is done by providing emergency protection and life-saving assistance to persons of concern to UNHCR, in the framework of the Evacuation Transit Mechanism (ETM) and by providing support to resettlement and complementary pathways for persons in need of international protection in the framework of the ETM.

Moreover, the EU-IOM Joint Initiative enables migrants who decide to return to their countries of origin to do so in a safe and dignified way, in full respect of international human rights standards and the principle of non-refoulement. It also provides sustainable reintegration assistance toreturning migrants to help them restart their lives in their countries of origin through an integrated approach to reintegration that supports both migrants and their communities.

Concrete projects under the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa include:

- Protection and sustainable solutions for migrants and refugees along the Central-Mediterranean Route - in Libya: Evacuation Transit Mechanism – IOM, UNHCR - €56 million (overall programme: €122 million)

- Supporting protection and humanitarian repatriation and reintegration of vulnerable migrants in Libya – IRC, IOM - €19.8 million

III. Humanitarian assistance

In 2020, €9 million was provided in 2020 and €9 million in 2021 from the EU budget for humanitarian assistance programmes, including health, protection, education in emergencies and other basic needs of vulnerable people regardless of their status. €3 million of the total of €9 million for 2021 are for the COVID-19 response and in support of the vaccination campaign.

IV. Root causes of irregular migration and forced displacement

The main objective of EU support in this area is to improve the living conditions of host communities, internally displaced persons and migrants in the Libyan municipalities by improving access to basic services, including health, education, infrastructure and public services. It also aims to promoting a culture of social cohesion and peace.

Concrete projects under the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa include:

- Managing mixed migration flows in Libya through expanding protection space and supporting local socio-economic development – local governance and socio-economic development pillar - UNDP, GiZ, UNICEF - €78.6 million (overall programme: €148 million)

- Recovery, Stability and socio-economic development in Libya - to support local communities including migrants and IDPs across Libya with improved basic social services and socio-economic initiatives, such as vocational training and entrepreneurship - AICS, UNDP, UNICEF- € 75 million

- Regional Development and Protection Programme (RDPP) phase II (development pillar) - IOM - € 1.2 million

- Regional Development and Protection Programme (RDPP) phase III (development pillar) - Norwegian Refugee Council, INTERSOS, ACTED, IMPACT, Danish Refugee Council, International Rescue Committee - € 6 million

V. Migration management

The EU supports the establishment of legislative and institutional framework for migration management in Libya both for migrants and for Libyans, as well as a rights-based approach for all migrants and developing new legislation on asylum in line with core international human rights standards:

- A project to improve border management both at maritime borders and at the southern land border building on the current Phase I and II of the “Support for Integrated Border and Migration Management in Libya (SIBMMIL)”, implemented by the Italian MOI, with €59 million funded under the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa.

- Managing mixed migration flows in Libya (mediation, community dialogue, social cohesion) - UNICEF €7million under the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa.

Countering migrant smuggling

- Common Operational Partnership along African migratory routes, work package on combatting organised migrant smuggling groups that are active in the Horn of Africa and Libya (activities implemented in Ethiopia and possibly Niger) – Dutch Public Prosecutor’s Office – €1.25 million from the EU budget for all recipients, including Libya

- Dismantling the criminal networks operating in North Africa and involved in migrant smuggling and human trafficking (North Africa (Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia) – UNODC - €15 million (Libya €5.2 M) from the EU budget.

Border management

- Support to Integrated Border and Migration Management in Libya - SIBMMIL"- Italian Ministry of Interior and IOM - (2 Phases: Phase I - adopted in December 2017 with € 42.2 million and Phase II – adopted in December 2018 with €15 million)

VI. Supporting a comprehensive approach to legal migration and mobility

Under the last call for proposals for pilot projects on labour migration launched on 28 February 2020, the priority remained North Africa. The geographical scope of future Talent Partnerships should be kept wide and, if appropriate, opportunities should be sought for Libya.

Annex 2: Member States’ bilateral engagement (to be completed by EU MS)

(Quelle: https://migration-control.info/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Libya.pdf)

Austria

- Co-funding of IOM project (RDPP NA). Existing

- Enforced cooperation in the fight against counter-smuggling andhuman trafficking incl. workshops, training and work shadowing. Planned

- Co-Participation EUBAM Libya (Secondment of 5 officials). Existing

Czechia

- Support of the Libyan coast guards. Existing

- V4 financial support for the implementation of project focusing on the integrated border and migration management. Planned

- Protecting and assisting refugees and asylum seekers in Libya, in cooperation with UNHCR. Existing

- Support of vulnerable migrants, IDPs, refugees and host communities through the creation of economic opportunities along migration routes (in cooperation with WFP). Planned

Germany

- IOM project: To broaden the outreach to migrants in Tripoli as well as municipalities with high populations of migrants in transit or living in urban areas to provide them with necessary information on the dangers of and alternative options to irregular migration. Planned

Denmark

- Support for Emergency Transit Mechanism (vulnerable refugees from Libya to Rwanda with UNHCR and Rwanda as implementing partners). Existing

Hungary

- V4 contribution to the “Support to Integrated border and migration management in Libya. Phase II: V4 countries have agreed to revisit the structure of the second phase, which has been divided into two separate projects: strengthening the Libyan border guard (15 million EUR) and supporting fighting against COVID-19 (20 million EUR). Existing

Italy

- Project “Support to Integrated Border and Migration Management in Libya – First Phase”, co-funded under EUTF for Africa, that includes technical assistance and capacity building initiatives in the areas of preventing and tackling irregular migration and migrant smuggling, border security, search and rescue at sea and in the desert. Existing

- Supply of additional means and equipment, as well as delivery of training within the aforesaid Project “Support to Integrated Border and Migration Management in Libya – First Phase” through a further financing under EUTF for Africa. Existing

- Supply of two “second-hand” rubber boats to the Libyan Coast Guard and Port security (LCGPS). Planned

- Technical assistance to the Libyan Coast Guard and Port security (LCGPS) and maintenance of its naval fleet. Existing

Malta

Malta is also considering providing its expertise on reception facilities. The two coordination centres have now been physically set up but work is still in the preliminary stages. Malta will also be sponsoring the maintenance of one asset of the Libyan coastguard. A technical team has already visited Tripoli to assess the vessels available to the Libyan coastguard. Planned

Netherlands

- Migrant Resource and Response Mechanism, IOM. Existing

- Protection and Assistance in Libya, UNHCR. Existing

- Document and ID fraud trainings by the Royal Netherlands Maréchaussée. Existing

Annex 3: Key Figures and Trends

(Quelle: https://migration-control.info/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Libya.pdf)

Irregular departures from Libya

- Total number of arrivals in Italy and Malta in 2021 via all countries on the Central Mediterranean route: 45 237 (compared to 25 679 in the same nine-month period in 2020)

- Libya was the main country of departure towards Italy in 2021 (20 082 migrants), followed by Tunisia (16 453), Turkey (6 237) and Algeria (857)

- Libya was the country of departure for all arrivals in Malta in 2021. Total number of arrivals in Malta in 2021: 470 (compared to 2 162 arrivals in the same period in 2020)

Irregular migration

- Irregular border-crossing of Libyan nationals to the EU: 1 069 in 2020 (379 in 2019) of which 607 in Hungary, 386 in Italy, 32 in Malta

- Illegal stay of Libyan nationals in the EU: 4,995 in 2020 (4,025 in 2019) of which 1 730 in France, 1 215 in Germany, 835 in Hungary

Return

- Libyan nationals ordered to leave the EU: 2 535 in 2020 (2 745 in 2019) of which 1 065 in France, 355 in Greece and 330 in Germany

- Return rate: 3% in 2020 (10% in 2019)

Asylum

- First time asylum applications: 1 755 in 2020 (2 310 in 2019) of which 535 in Germany, 270 in France, 230 in Italy

- First instance asylum decisions: 1 635 in 2020 (2 185 in 2019)

- EU recognition rate excluding humanitarian protection: 50% in 2020 (49% in 2019)

- EU recognition rate including humanitarian protection: 53% in 2020 (51% in 2019)

Forced displacement in Libya, migrants in detention, evacuations, voluntary return

- 42 458 registered refugees and asylum-seekers; 223 949 IDPs; 642 408 IDP returnees;

- 16 026 disembarkations in Libya in 2021 (until 12 July 2021);

- 6 134 migrants in detention centres (on 12 July 2021);

- 6 379 persons of concern evacuated by UNHCR since November 2017 via ETMs in Niger/Rwanda for resettlement in the EU and globally:

- 1 738 persons: resettlement departures directly from Libya

- 3 318 persons: Humanitarian evacuations to ETM Niger

- 515 persons: Humanitarian evacuations to ETM Rwanda

- 808 persons: Humanitarian evacuations to Italy ( in 2017-2018- 2019)

- 53 135 migrants returned by IOM since May 2015 via humanitarian evacuation flights

Legal migration

- First time residence permits: 3 669 in 2019 of which 1 859 in Germany, 299 in Italy, 268 in France. No available data for 2020

- Total valid residence permits: 18 365 in 2019 of which 7 020 in Germany, 2 596 in Italy, 1 756 in France. No available data for 2020

Visas

- Short stay visa applications in the EU: 2 964 in 2020 (11 254 in 2019)

- Share of Multiple Entry Visas (MEVs): 91.4% in 2020 (81% in 2019). Top Member State of multiple-entry visa issuance in 2020: Italy (1 994)

- Visa refusal rate: 23.8% 2020 (20.5% in 2019)

Footnotes

-

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL; see also https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Libyen.

↩ -

Cole, Peter und Fiona Mangan (2016): Tribe, Security, Justice, and Peace in Libya today, Peaceworks, https://www.usip.org/publications/2016/09/tribe-security-justice-and-peace-libya-today, p. 5; Faath, Sigrid (2017): Politische Parteien in Nordafrika. Ideologische Vielfalt – Aktivitäten – Einfluss, p. 204, https://www.kas.de/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=4c572892-7e5f-7cf4-6f87-63feefeb9969&groupId=252038.

↩ -

Werenfels, Isabelle (2008): Qaddafis Libyen. Endlos stabil und reformresistent?, SWP-Studie, p. 8, https://www.swp-berlin.org/publikation/qaddafis-libyen.

↩ -

Cole, Peter; Mangan, Fiona (2016): Tribe, Security, Justice, and Peace in Libya today, Peaceworks, pp. 5–6, https://www.usip.org/publications/2016/09/tribe-security-justice-and-peace-libya-today.

↩ -

Halm, Heinz (2017): Die Araber. Von der vorislamischen Zeit bis zur Gegenwart, München. C.H.Beck, p. 125; Anderson, Lisa,(2011): Demystifying the Arab Spring. Parsing the Differences Between Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/libya/2011-04-03/demystifying-arab-spring.

↩ -

Action Fiche I, Action fiche of the EU Trust Fund to be used for the decision of the Operational Committee. Managing mixed migration flows in Libya through expanding protection space and supporting local socio-economic development. (T05-EUTF-NOA-LY-03), p.7, https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/sites/euetfa/files/t05-eutf-noa-ly-03.pdf; EUTF, European Union Emergency Trust Fund for stability and addressing root causes of irregular migration and displaced persons in Africa. Board Meeting Minutes, 12.11.2015, p. 2; EUTF, Minutes of the fourth board meeting of the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF for Africa), 24.04.2018, p. 3.

↩ -

Polimeno, Maria Gloria (2021): Report on Citizenship Law Libya, 2021, p. 2, https://cadmus.eui.eu//handle/1814/71160.

↩ -

In addition to Polimeno, Maria Gloria (2021): Report on Citizenship Law Libya, see also Stocker (2019): Citizenship on hold: Undetermined legal status and implications for Libya´s peace process, p. 7, https://www.eip.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Citizenship-on-hold-EIP-policy-paper-July-2019.pdf.

↩ -

Dietrich, Alexander (2011): „Ich fühle, dass es zu Ende geht mit Gaddafi“, https://www.welt.de/politik/ausland/article12586732/Ich-fuehle-dass-es-zu-Ende-geht-mit-Gaddafi.html; Spiegel Online, 19.02.2011, https://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/aufstaende-in-arabien-gaddafi-kappt-facebook-und-twitter-a-746597.html.

↩ -

Gehlen, Martin, Wie Gadhafi seinen größten Gegner empfing, Zeit Online 02.03.2011, https://www.zeit.de/politik/ausland/2011-03/gadhafi-bengasi-uebergangs-rat.

↩ -

,11. Haftar was involved in Gaddafi's 1969 coup against King Idris, commanded Libyan intervention forces in Chad as a colonel under Gaddafi, was taken prisoner and later worked for the CIA in the United States for years. After the uprising broke out, he returned to Libya and promoted himself to general. Today, he is the actual ruler in Cyrenaika.

↩ -

12 Lacher, Wolfram (2016): War Libyens Zerfall vorhersehbar?, ApuZ, pp. 2–4, https://www.bpb.de/apuz/232421/war-libyens-zerfall-vorhersehbar.

↩ -

13 Al-Serori, Leila, (2019): Frankreichs unscharfe Linien, https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/libyen-frankreich-1.4401103; International Crisis Group (2020): Turkey Wades into Libya’s Troubled Waters, https://www.crisisgroup.org/europe-central-asia/western-europemediterranean/turkey/257-turkey-wades-libyas-troubled-waters; Tagesschau 18.01.2020: Wer will was in Libyen?, https://www.tagesschau.de/ausland/faq-libyen-101.html.

↩ -

14 Local conflicts also repeatedly revolve around the control of strategic nodes for the smuggling business or oil infrastructure. Murray, Rebecca (2019): Southern Libya Destabilized. The case of Ubari, p. 4, p. 11, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/southern-libya-destabilized-the-case-of-ubari/.

↩ -

15 Lacher, Wolfram (2016): War Libyens Zerfall vorhersehbar?, ApuZ, pp. 2–4, https://www.bpb.de/apuz/232421/war-libyens-zerfall-vorhersehbar.

↩ -

16 Beaumont, Peter (2021): War crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Libya since 2016, says UN, Guardian 04.10.2021, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/oct/04/war-crimes-and-crimes-against-humanity-committed-in-libya-since-2016-says-un; Guardian 08.10.21: Reports of physical and sexual violence as Libya arrests 5,000 migrants in a week, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/oct/08/reports-of-violence-libya-arrests-5000-migrants.

↩ - ↩

- ↩

- ↩

-

20 Action Fiche I, Action fiche of the EU Trust Fund to be used for the decision of the Operational Committee. Managing mixed migration flows in Libya through expanding protection space and supporting local socio-economic development. (T05-EUTF-NOA-LY-03), p.4, https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/sites/euetfa/files/t05-eutf-noa-ly-03.pdf.

↩ -

21 Binder, Clemens et al. (2018): EU Grenzpolitiken – der humanitäre und geopolitische Preis von Externalisierungsstrategien im Grenzschutz. Working Paper, p. 6, https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/59994/ssoar-2018-binder_et_al-EU_Grenzpolitiken_-_der_humanitare.pdf; see also Zaiotti, Ruben (2016): Mapping remote control. The externalization of migration management in the 21st century, pp. 6–8, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281750681_Mapping_Remote_Control_the_Externalization_of_Migration_Management_in_the_21st_century.

↩ -

22 Keilberth, Mirco(2018): Italien und Libyen gegen Migranten, https://taz.de/Kooperation-gegen-Fluechtlinge/!5521779/; Bendiek, Annegret und Bossong, Raphael (2019): Grenzverschiebungen in Europas Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik, https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/studien/2019S19_bdk_bsg_web.pdf.

↩ -

23 Polimeno, Maria Gloria (2021): Report on Citizenship Law Libya, p. 9, https://cadmus.eui.eu//handle/1814/71160.

↩ - ↩

-

25 Dietrich, Helmut (2004): Die Front in der Wüste, Konkret 12/2004.

↩ -

26 Mixed Migration Centre (2021): Quarterly Mixed Migration Update: North Africa,p. 7, https://mixedmigration.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/qmmu-q1-2021-na.pdf.

↩ -

27 Action Fiche IV, Action Document for the implementation of the North Africa Window. Integrated Approach to protection and emergency assistance to vulnerable and stranded migrants in Libya, (T05-EUTF-NOA-LY-06), p. 7, https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/sites/euetfa/files/t05-eutf-noa-ly-06.pdf.

↩ -

28 Mixed Migration Centre, Quarterly Mixed Migration Update: North Africa, 2021, pp. 7–8 https://mixedmigration.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/qmmu-q1-2021-na.pdf.

↩ -

29 Bialasiewicz, Luiza (2012): Off-shoring and Out-sourcing the Borders of EUrope: Libya and EU Border Work in the Mediterranean, Geopolitics, p. 853, https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Off-shoring-and-Out-sourcing-the-Borders-of-EUrope%3A-Bialasiewicz/b506b6a5d97e2cdc36a8afc8bf4b5e3824b7db01.

↩ -

30 Murray, Rebecca (2019): Southern Libya Destabilized. The case of Ubari, 2019, p. 11, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/southern-libya-destabilized-the-case-of-ubari/; Westcott, Tom (2019): Feuding tribes unite as new civil war looms in Libya´s south, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/feuding-tribes-unite-new-civil-war-looms-libyas-south; Minority Rights Group International (2018): Libya Tebu, https://minorityrights.org/minorities/tebu/.

↩