Nigeria

Published April 30th, 2023 - written by: Kwaku Arhin-Sam

Basic Data and Short Characterisation

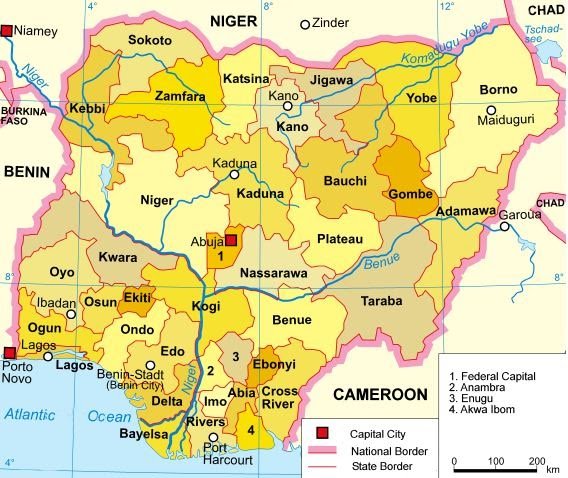

The Federal Republic of Nigeria is a country in western Africa. With an estimated population of over 220 million as of 2022, it is the most populous country on the continent and 7th in the world.[1] Nigeria is Africa’s largest economy and leading oil producer and wields significant political and economic influence in the West Africa Region. After gaining independence in 1960 from British colonial rule, the country was ruled by one military leader after another until 1999. After the death of the then-military head of state, Gen. Sani Abacha, in 1998, the country was ruled for less than a year by Gen. Abdusalami Abubakar and then ushered in an era of democratic rule. It adopted a new constitution in 1999, paving the way for civilian government and a president who exercises executive powers over 36 states and a federal capital territory. As of 2015, the country has over five hundred ethnic groups and languages. It has over 90 million Muslims who reside mainly in the North and about 87 million Christians in the South, representing 50% and 48% of the population, respectively. In 2017, Nigerians made up the highest group of illegalised arrivals (18, 100 migrants) from West Africa to Europe (arrivals by sea in Italy). Despite the war against Islamic insurgency in north-eastern Nigeria, which causes over 3.2 million internally displaced persons (IDPs)[2] and 333,411 refugees[3], most Nigerians arriving in Europe are from Southern Nigeria. Reasons behind international migration in Nigeria can be attributed to a lack of prospects and opportunities, unemployment, political neglect, as well as – albeit to a minor degree – conflicts.

Economy and Government

Since 1999, Nigeria has been a multiparty democracy. Its national assembly consists of the Senate (the upper chamber) with 109 senators and the house of representatives (lower chamber) with 360 representatives. Governance conditions have broadly improved over the past two decades. In 2015, the first democratic power transfer between political parties occurred in Nigeria when former military ruler Muhammadu Buhari became the president. Many Nigerians anticipated his election to usher the country into prosperity and reduce corruption. President Buhari was re-election in 2019 in an election marred by historically low turnout, allegations of pervasive vote-buying, and widespread violence, which heightened concerns over Nigeria’s democratic trajectory. The February 25, 2023 election[4] has seen former Lagos governor Bola Tinubu, from the ruling All Progressives Congress party (APC) government, elected president in one of the most controversial and highly disputed elections following the highest level of reported polling irregularities. Before the March 11, 2023, gubernatorial elections, Nigeria’s political landscape was dominated by the ruling APC, which holds 217 out of 360 seats in the National Assembly and 64 out of 109 in the Senate, 19 out of 36 State Governors.

As the biggest economy in Africa, Nigeria’s economy is predominantly petroleum-based. However, since the 2008-09 global financial crisis, efforts have been made to diversify economically through strengthening other sectors such as agriculture, telecommunications, and services. Nigeria follows a blended economic model, combining state-owned and private businesses. Nigeria is equipped to emerge as a global economic powerhouse with massive oil reserves, vast agricultural and service sector potential, and a youthful population. The country’s economy was impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic when GDP shrunk from 448.12 billion USD in 2019 to 432.29 (representing a 4% decrease) in 2020 (World Bank, 2022).

Nigeria’s challenges include corruption, infrastructure gaps, insecurity, and a failure to adequately diversify the economy away from petroleum products, which has constrained economic growth and development. Consequently, unemployment is high in the country. In 2020, the country recorded a 27% unemployment rate (NBS, 2020).

Migration in Nigeria

Since immemorial, migration has been a crucial part of everyday life for many Nigerians. It has evolved over the years from within the country (internal migration) to crossing the borders of Nigeria in the colonial / post-colonial period (international migration).

A large number of Nigerians migrate internally. Internal migration patterns in Nigeria are characterised by rural-rural, rural-urban, urban-urban, and inter-state migrations. In addition, forced migration in the form of internal displacements are part of internal migration. Drivers of internal migration are security, education, economic, and climate factors.

Many Nigerian youths migrate from villages and remote parts of the country to bigger cities (rural-urban or inter-state migration), searching for education, jobs and other economic opportunities. Cities like Lagos, Port Harcourt, Kano and Abuja are popular destinations for such migrants. Other federal-state capitals also attract rural-urban migrants who may be seasonal migrants or permanent dwellers.

Several conflicts in Nigeria continue to drive people away from their homes to different parts of the country. For example, the ongoing war between the Nigerian Army and Boko Haram/ Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWAP) militants in the Northeast has displaced many Nigerians. Over 3.2 million displaced people stay within the country (Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs)). In addition, trans-humance (herders) – farmer conflicts, particularly in north-central Nigeria, lead to internal displacement.

Again, Nigeria’s climate-induced migrations come about due to flooding, wildfires, and lack of rain. Extreme climate conditions often destroy livelihoods and push people (approximately 24,400 climate-induced IDPs as of 2021) to migrate.

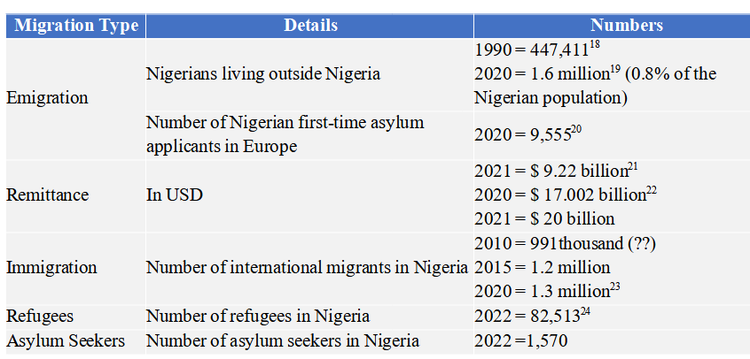

Furthermore, international migration has increased since Nigeria’s independence. Nigeria’s international migration patterns include irregularised migration, diaspora migration, asylum seekers, immigration, refugees, and asylum seekers. Furthermore, many forcibly displaced Nigerians (approximately 333,411) are forced to become refugees in neighbouring Cameroon, Niger, and Chad. Nigeria is an important destination, origin, and transit country for international migration. Besides emigration (regular, irregular, refugees and asylum seekers), the country attracts many immigrants with diverse backgrounds, goals, and expectations who enter Nigeria to stay or transit to other destinations. A 2018 global attitudes survey indicated that 45% of adult Nigerians plan to move to another country within the next five years. The number of Nigerians living outside Nigeria has almost tripled between 1990 and June 2020, from 447,411 (Unicef Migration Profiles) to 1,670,455 in June 2020 (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division), representing about 0.8% of the country’s population.

Likewise, Nigeria hosts 82,513 refugees and 1,570 asylum seekers as of May 2022 (UNHCR, 2022). The highest refugee population in Nigeria are Cameroonians (77,253) fleeing armed conflict due to separatist agitation in Anglophone Cameroon. Many Cameroonian refugees are primarily located in southern Nigeria, close to the border with Cameroon. They are readily accepted in Nigerian communities due to common ethnocultural ties and because they speak English and Pidgin.

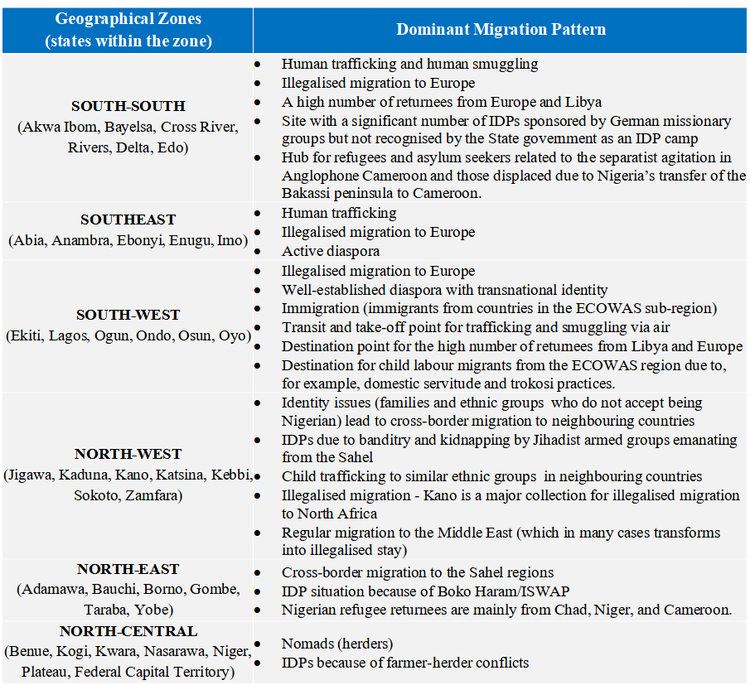

The table below shows the various states in Nigeria and the dominant migration patterns in the states.

Key Migration Patterns in Nigeria

Over the years, migration, including immigration, diaspora migration, illegalised migration, refugees and internally displaced people in Nigeria, and refugees and asylum seekers from Nigeria, have become prominent topics in Nigeria’s public and political sphere. Migration has attracted policy attention, become part of social discourses and is considered relevant for Nigerian and foreign actors’ interests. For each migration type, some actors are more active than others. Understanding these migration types and their respective actors’ interests determines the extent of attention in political and public discourses domestically and outside the country.

Immigration in Nigeria

Immigration to Nigeria has a long history. Throughout pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial history, Nigeria has attracted an immigrant population, mainly from the West African region. Despite regular migratory movements within the present central and western Africa, Nigeria recorded early waves of immigration during the early days of colonial times[5] when an estimated 30,000 Tuaregs moved from Niger to Nigeria (Abba, 1993; Mberu, 2010).

During colonial rule, Nigeria attracted many labour migrants from different West African countries, like Ghana, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad, Mali, Guinea, Cape Verde, and Togo (Udo, 1975; Adepoju, 1996). Many of these immigrants came to Nigeria to meet up the British colony’s need for a large labour force in mining, public administration, and plantations, especially after 1956 when oil was discovered in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria (Dunn, 2008); (Mberu & Pongou, 2010).

The immigration trend during the colonial era continued after Nigeria’s independence from 1960 to the early 1970s. The high immigration rate in Nigeria was interrupted by conflicts, particularly the political power struggle between the North and the South, where mainly military officers from the North were killed in a coup believed to be orchestrated by an Igbo officer from the South, and northern groups in reprisal attacks killed many Igbo residents in the North. The result was the Biafra civil war of 1967-1970 between the newly created Biafran state and Nigeria. These conflicts made Nigeria unattractive to immigration (Ikwuyatum, 2016). Another factor that contributed to reducing immigration during these times was the introduction of the Immigration Act in 1963. The Act, the first state policy relating to migration, tightened the monitoring and documentation of immigrants, restricted entry to specified groups, and set out requirements for entry and stay in Nigeria (Adepoju, 2005).

Immigration and immigration policy in Nigeria took another dimension after the country ratified the ECOWAS protocol on the Free Movement of Goods, Capital, and People in 1980. The Free Movement of Persons, Residence and Establishment under the Protocol stipulates, among other things, the right of ECOWAS community citizens to enter, reside and establish economic activities in the territory of member states (Aderanti et al., 2007). Between the 1970s and early 1980s, Nigeria’s economy was booming due to the oil-led employment opportunities in several sectors of the economy. The positive economic performance of Nigeria at the time, coupled with the coming into force of the free-movement protocol, attracted many ECOWAS citizens. Between 1983 and 1985, there was a sharp decline in world prices of oil. As a result, Nigeria’s economy, coupled with violence and political repression, took a downturn. The vast number of migrants in the Nigerian labour market had fuelled the already existing job crisis, and pressure to emigrate had increased among Nigerians. Confronted with these economic hardships and political problems, the government responded by expulsing many undocumented ECOWAS citizens whose 90 days residence permits and the grace period under the ECOWAS protocol had expired. This mass expulsion targeted labour migrants, including about 1 million Ghanaians (De Haas & Flahaux, 2016). The Structural Adjustment Programme in 1986 brought additional economic hardship to Nigeria, making it less attractive to many ECOWAS citizens.

The 2020 immigration data shows about 1.25 million immigrants[6] in Nigeria, representing 0.61% of the country’s population (UN DESA, 2020). The proportion of immigrants to Nigeria’s population is below the global average (3.6%) and in West Africa (1.9%). This proportion also means Nigeria has the lowest rate of immigrants to the population. This is not surprising because of Nigeria’s population size. ECOWAS citizens constitute the highest number of immigrants in Nigeria coming from countries such as Benin, Ghana, Niger and Togo (ibid).

Regular (Diaspora) Migration

The Nigerian National Migration Policy (NMP) defines diaspora as populations outside their country of origin, usually sustaining ties and developing links with the country of origin and across countries of settlement/residence. This section uses the term diaspora migration mainly for regular migrants outside[7] Nigeria.

According to Wapmuk et al. (2014), the driving force behind the formation of the prominent Nigerian diaspora is linked to globalisation and racialised capitalism[8]. Factors such as slavery, colonial labour policies, post-colonial conflicts and structural adjustment programme-induced economic hardships are behind the enormous Nigerian diaspora. Like immigration, emigration in Nigeria has a long history dating back to the colonial era. Education was the main reason for migration, primarily to the United Kingdom. After their education, many migrants stayed back in the UK for work. This trend continued after independence as the United States became another attractive destination in addition to the UK (de Haas, 2006; Mberu & Pongou, 2010). In post-colonial Nigeria, the Biafra war of 1967 – 1970, economic hardships, and neo-liberal policies contributed to high emigration rate (Mberu & Pongou, 2010, Wapmuk, Akinkuotu, & Ibonye, 2014).

Furthermore, international migration began diversifying in the early 1980s. Within this period, the country witnessed an increase in emigration, primarily due to the economic challenges caused by the decrease in oil prices in the late 1970s and early 1980s (Black et al., 2004). Apart from destinations like the UK and the US and wealthy economies in Africa like Gabon, Botswana, and South Africa, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, Italy, and Ireland emerged as new destinations of labour migrants from West Africa, including Nigeria (Black et al., 2004; de Haas, 2006).

The Nigerian diaspora comprises people from different parts of the federation. Nevertheless, the majority originates from the country’s South-South, Southeast, North-Central, and South-West geopolitical zones (ICMPD & IOM, 2010). For example, research on Nigerians in the UK shows that most are Yoruba from the South-West, Ibos from the Southeast, and Ogonis and Edos from the South-South (Marchand, Langley, & Siegel, 2015;).

As of 2015, it was estimated that over 15 million Nigerians live in the diaspora, of which over 27% live in the US and the UK (UNESA 2015, Policy Development Facility, 2017). A high number of Nigerians in the diaspora are highly skilled.[9] As of 2000, 34.5% of all Nigerian migrants in OECD countries had tertiary education. Likewise, 83% and 46% of Nigerian migrants were high-skilled workers in the US and Europe alone (Docquier & Marfouk, 2004; OECD, 2012; Darkwah & Verter, 2014). Since 2000, approximately 10.7% of tertiary-educated Nigerians have emigrated (World Bank, 2011). The bulk of Nigeria’s highly-skilled migrants is in the US and Canada. Apart from the UK, most Nigerian migrants in Europe are low-skilled (OECD, 2019).

Today, the considerable number of Nigerian diaspora pays off through remittances. For example, in 2018, Nigeria became the largest remittance recipient country in sub-Sahara Africa after receiving more than $24.3 billion in official remittances (an increase of $2 billion from 2017), representing a total of 6.1% of Nigeria’s GDP (World Bank, 2019). However, the country received a sharp decline in remittances in 2020 (only $17.21 billion) due to the Covid-19 pandemic. By 2021 however, Nigeria received remittances inflows of close to $20 billion, representing four times the Foreign Direct Investments into the country.

Illegalised Migration (to Europe)

The majority of illegalised migration originates from south-south and southeast Nigeria. Edo State (Benin City, to be precise) is often described as the corridor to Europe (Hoffmann, 2018; Agbakwuru, 2018; O’Grady, 2018). This is because many Nigerian migrants with irregular status in Europe are from Edo State. The state ranks high in the number of returnees or rescued victims of traffickers from Libya who were initially destined for Europe.[10] When migrants with irregular status arrive in Europe, many rely on the asylum application systems in the host European country in an attempt to regularise their stay. Overall, Nigeria has the highest number of asylum applicants (see the section on Refugees and Asylum Seekers from Nigeria) in the EU compared to other West African countries (Eurostat, 2019).

Historically irregular migration from Edo state dates back to the 1980s. Many Nigerians, including women from the Edo state, emigrated to Italy, responding to the high demand for low-skilled agricultural labour (Carling, 2006). While in Italy, some of these women sought other work sources, including prostitution, when agricultural work became competitive, and opportunities began to diminish. Many women became popularly known as “the Madams” and started bringing other women to join. As regular migration across Europe became more restricted, many of these Madams sought diverse ways, including irregular means via trafficking and smuggling networks (Carchedi, 2000; Wolthuis & Blaak, 2001; Baldoni, Caldarozzi, Giovanetti, & Minicucci, 2014) to go around these migration restrictions.

Today, much of the illegalised mobility from Benin City can be attributed to poverty, unemployment, and material incentives like financial remittances for families and investments (Green, Wilke, and Cooper, 2018). In addition, the lack of hope and prospects in Nigeria pushes young girls and boys who see migration as the only way to a hopeful future to migrate illegally, some becoming victims of sex and other forms of human trafficking (Osezua, 2016; Plambeck, 2017).

Furthermore, misinformation plays a crucial role in illegalised migration in Nigeria. Many times, smugglers and so-called migration agents deliberately misinform and manipulate households into believing that there are excess employment vacancies in Europe. In return, many families and young persons pay these “agents” to facilitate their migration. They do not inform their “clients” about the deadly challenges associated with crossing the Sahara desert, the modern-day slavery situation in Libya, pushbacks by Frontex and a high number of deaths in the Mediterranean Sea, arrests and interrogations, integration and accommodation problems, the growing anti-migrant sentiments in Europe, and the lack of access to education and employment due to their irregular status.

Many irregular Nigerian migrants start their journey from Benin City, transit through Kano in northern Nigeria, Agadez in the Niger Republic, and then on to Libya before crossing to Europe via the Central Mediterranean to Italy or Malta. Current figures show an increasing shift towards the Atlantic/Western Mediterranean route to Spain (Brenner, Forin, & Frouws, 2018). Due to the tightening of the Niger (Agadez) route, Mali has become an attractive route for traffickers despite the current security situation and instability in Mali. Smugglers and traffickers make different arrangements with the various factions in the Mali war for ‘safe’ passage. Weaker border controls and corruption at these borders further aid the movement regimes of these traffickers within the ECOWAS region.

Discussions on irregular migration from Sub-Sahara Africa to Europe, mainly from Nigeria, often ignore the desperation of many young people without alternative prospects in their home country. These people face increasingly difficult situations throughout their journeys to Europe due to restrictive migration policies. The increasing use of illegal and life-threatening migration pathways results from the absence of regular/legal migration pathways. Equally, the scarcity of legal pathways creates marked opportunities for facilitators of illegalised mobility, increasingly criminalised as migrant smugglers, as well as traffickers who are often linked to organised crime. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), human trafficking involves the recruitment, movement or harbouring of people for exploitation – such as sexual exploitation, forced labour, slavery or organ removal. The smuggling of migrants involves assisting migrants in entering or staying in a country without the statutory documentation for financial or material gain. In the broader framework of illegalised migration, the distinction between the smuggling of persons and the trafficking of persons is sometimes blurred (Salt, 2000). Thus, a migrant who agrees to be smuggled can quickly become trafficked along the migratory route.

Internally Displaced Persons in Nigeria

As of March 2022, there were 2,197,824 registered IDPs in Nigeria (UNHCR, 2022). Effects of climate change, natural disasters, and conflicts (insurgency, farmer-herder and inter-communal clashes) all account for internal displacements in Nigeria. However, a major cause of internal displacement in Nigeria has been the conflict between the Nigerian government and the Boko Haram insurgents. It started in 2009 when the Nigerian security forces clamped down on an Islamic sect, killing 800 people (Ioannis Mantzikos et al., 2013). Among those who died in this operation was Mohamed Yusuf, the leader of an Islamic sect called Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati Wal-Jihad – meaning ‘People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teachings and Jihad’ also known as Boko Haram, which means “Western education is forbidden” (Adelaja, A, Labo, A, & Penar, 2018; Home Office, 2017; Ioannis Mantzikos et al., 2013). This Islamic sect which was basically on a low profile since its inception in the early 2000s became highly violent after the death of Mohamed Yusuf (Adelaja, A, Labo, A, & Penar, 2018; Ioannis Mantzikos et al., 2013).

In 2014, with authorisation from the African Union (AU), the Lake Chad Basin Commission reactivated the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF)[11] to conduct combat operations against Boko Haram, intercept trafficked weapons, free hostages, and encourage defections. This was after Boko Haram extended its insurgency to neighbouring countries of the Lake Chad Basin (Niger, Cameroon, and Chad).

In August 2016, Boko Haram split into two factions. The split was ideological and about engaging or targeting attacks. The new group, Islamic State-West Africa Province (ISWAP), with links to the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, wants to engage with Muslims rather than target them. On the other hand, the remaining members of Boko Haram continue to target all, including Muslims (Mahmood, 2018).

In 2018, in collaboration with the MNJTF, the Nigerian Army scaled up its counter-insurgency campaign with significant offensives against the insurgents in Yobe and Borno State. The same year, the Jihadists intensified their operations, changed tactics and staged deadly attacks on the Nigerian Army. This violent crisis has impacted all demographics of the affected communities. Girls and women were abducted, raped, and turned into sex slaves, while boys and men were forcefully recruited to either fight at battlefronts or commit suicide bombings.

In addition to the Boko Haram insurgency, other conflicts and situations have led to internal displacement in Nigeria. In 2018, Adamawa state experienced deadly inter-communal disputes involving more than 100 communities leading to further displacement in the Northeast. Also, political violence and clashes in the last elections (2015, 2019 and 2023) led to internal displacement across the country.

Refugees and Asylum Seekers from Nigeria

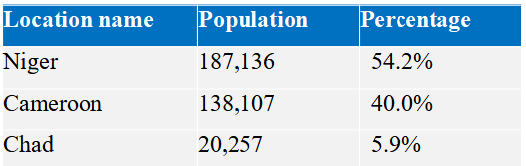

The Nigerian government’s fight against the Boko Haram insurgency in northern Nigeria continues to be a complex situation that bothers migration and humanitarian issues. In addition to the IDP situation, the Boko Haram insurgency has forced many Nigerians to flee to neighbouring countries for asylum and refugee protection. As of October 2022, there were a total of 345,500 Nigerian refugees in Niger (187,136), Cameroon (138,107), and Chad (20,257).

Countries in the Lake Chad Basin (Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, and Chad) have struggled with a difficult humanitarian situation since the Boko Haram insurgency spread from Nigeria to these neighbouring countries in 2014. The attitude and reaction of Niger and Chad towards Nigerian refugees have been warmer than the Cameroonian government’s attitude towards Nigerian refugees. The Cameroon military has, since 2015, deported over 100,000 Nigerian refugees, often on suspicion of being Boko Haram members. According to Human Right Watch, many deported Nigerian refugees from Cameroon often end up in Borno State, where the war is ongoing. These returnees go back to areas of war as they become displaced and destitute in Nigeria. (Human Rights Watch, 2017; 1). The Nigerian government has criticised Nigerian Refugee deportations from Cameroon as going against the tripartite repatriation agreement between Nigeria, Cameroon and UNHCR, the 1954 UN convention on statelessness and the 1969 Organisation of African Unity (OAU) convention governing the specific aspects of refugee problems in Africa[12].

Aside from Nigerian refugees in neighbouring countries (Chad, Niger, Cameroon), Nigeria has the highest number of asylum applicants to the EU compared to other West African countries. In 2018, 25,755 Nigerian migrants applied for asylum across Europe (Eurostat, 2019).

In addition to the Boko Haram and other none state fighters, reasons for Nigerians seeking asylum in the EU include state persecution of militant groups in the Niger Delta, separatist movements, farmers-herders conflicts, and student cultism (European Asylum Support Office (EASO, 2019).

EU Engagement and Migration

Following the so-called 2015 migration crisis in Europe, the European Union and its member states scaled up efforts to externalise its borders to African countries,

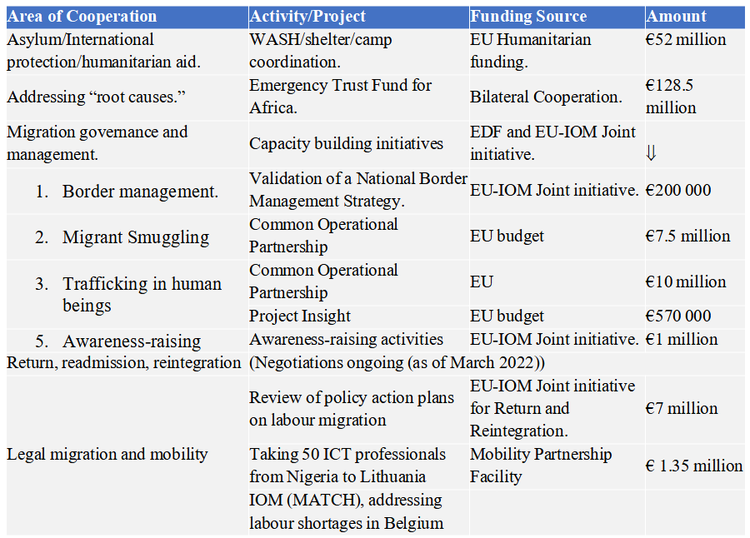

As a response, the EU introduced several initiatives, including setting the 2015 European Agenda on Migration, organising the Valletta summit and coming up with the Valletta Action Plan, and establishing the EU Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF). These added to instruments established in earlier EU frameworks such as Common Agenda on Migration and Mobility (CAMM) and Migration Partnerships. In all these initiated responses to the 2015 migration “crises”, the EU considered Nigeria a priority country, which it continues to occupy in the EU’s external migration policies. Nigeria has been central in various frameworks, agreements, and financial instruments. For example, Nigeria was the first country to sign a CAMM in 2015 and one of the five countries(including Ethiopia, Mali, Niger, and Senegal) targeted by the MPF.

There are several reasons why Nigeria is critical to the EU’s engagement and cooperation on migration in sub-Sahara Africa. First, Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa and thus contributes to most migrants from Sub-Sahara Africa trying to enter the EU. Secondly, Nigeria is both an origin and transit country. Thirdly, Nigeria plays the role of superpower in the Western Africa region and thus poses some political, social, and economic powers that can come in handy for the EU’s interests.

The importance of Nigeria in the EU’s external migration governance agenda has resulted in relatively high EU funding granted to Nigeria. Between 2006 and 2019, Nigeria received not less than 425 million Euros from various EU-funded projects. In addition, Nigeria is one of the 26 countries that benefit from the EU-IOM Joint Initiative for Migrant Protection and Reintegration, launched in 2016 to facilitate the ‘voluntary’ return of migrants to their countries of origin.

Seven years after the “European migration crisis”, Nigeria is still critical for the EU’s external migration agenda in Africa. On the first page of a new EU Action on Nigeria (draft) released by the EU in September 2021, “the EU recognises Nigeria’s pivotal importance in the economic, social and political landscape in Africa”. For the next seven years (2021 – 2027), the EU seeks to strengthen its migration partnership comprehensively and “is committed to the reinvigoration of a strategic political partnership with Nigeria” (EU, 2021. p.1). The EU acknowledges its considerable investment in Nigeria in migration partnership cooperation and outlines the following areas of collaboration with the West African superpower.

At the EU member state level, several cooperation partnership projects have been established by countries like Germany, Sweden, and Lithuania. Swedish cooperation on migration in Nigeria has been focused on deepening migration governance. Many more EU countries have focused on campaigns to discourage irregular migration. Establishing the Nigeria-German Migration Centre in Lagos (with other offices in Abuja and Benin City) is one example of Germany’s cooperation projects on migration. The migration centre aims to provide information on job prospects in Nigeria and information on regular migration to potential migrants and Nigerian youths. The project offers training and workshops on skills for seeking jobs. One aspect of the migration centre that needed to be clarified was the impression that the Centre would provide Nigerians with information on potential job prospects in Germany. In effect, the policy to establish the Centre is interested in educating and informing Nigerians to find jobs in Nigeria and reducing migration to Europe. At its establishment, the Centre had little to do with genuinely establishing regular migration pathways for Nigerians, which the Nigerian government is interested in establishing with Germany.[13] Perhaps, initiatives such as the Digital Explorers[14] can serve as a reference point to build pathways for regular migration in other sectors.

Indeed, EU-Nigeria cooperation on migration is marked by challenges and opposing interests despite the EU’s financial investment and Nigeria’s vital position in the EU’s external migration policies. The two partners have both diverging and converging interests. For example, take border management or control; Nigeria has 114 recognised land border posts and several ungoverned land borders. An immigration commissioner interviewed in this study blamed the porous nature of borders for human smuggling and trafficking in Nigeria. Even for the recognised posts, maintaining all these borders puts enormous pressure on the country’s financial and human resources. As a result of the EU-Nigeria migration cooperation, the EU has supported Nigeria’s border management. For example, a project like the Free Movement and Migration (FMM) in West Africa was one of the initiatives for border management across the ECOWAS sub-region. The FMM project trained immigration officers in ECOWAS member countries, including Nigeria. In addition, all Nigerian international airports (Enugu, Kano Port Harcourt, Abuja, and Lagos)got security upgrades (hardware, software, and training) to meet the Airport Excellence (APEX) standards under EU support for border control. In the broader sense, the EU and Nigeria are interested in seeing well-managed/ controlled borders. Nigeria wants border control to counter human trafficking, given more general security considerations. The EU is interested in border control to reduce illegalised mobility towards Europe.

Besides border management, the EU and Nigeria’s interests converge on reducing the humanitarian challenges resulting from the Nigerian government’s war with Boko Haram. Closely related to this interest is ensuring security in the Sahel and Horn of Africa regions.[15]

Return readmission and reintegration are the most outstanding diverging interests observed from the EU/Nigeria migration partnership/cooperation. On the one hand, Nigeria is aware of illegalised migration originating from the country. In contrast to the EU and its member states, the government is more interested in diaspora engagements to attract investments and increase remittances for development. On the other hand, EU and EU-member states have shown more interest in irregular migration and return, readmission, and reintegration, even though Nigeria is interested in increasing regular legal pathways for Nigerian migrants. Despite failing to secure a return and readmission agreement with Nigeria, the EU has shown in its action plan for Nigeria on migration cooperation that it still aims to obtain such a formal agreement (Council of the European Union, 2021).

Impact of EU’s Involvement in Nigeria on Migration

Since 2015, EU-Nigeria development cooperation has deepened on migration mainly because of the focus of EU external migration policies on Nigeria. The EU’s development cooperation with Nigeria has undoubtedly impacted migration governance/management and migration discourses in Nigeria, contradicting the EU’s failure to finalise a return and readmission agreement. An analysis of the impact of EU-Nigeria cooperation is provided below.

A new focus of EU-Nigeria bilateral cooperation

“Since the EU prioritised migration, bilateral cooperation on trade, for example, have all been pushed back. But we would also like to see trade cooperation back on the table” (Amanda, Migration Researcher on Nigeria and ECOWAS – Interview conducted in March 2019).

Bilateral cooperation between Nigeria and the EU has been prioritised on migration by the EU, wrapped under the ‘disguised’ narrative of finding the “root causes” of migration. Notwithstanding critiques of using development cooperation funding for migration problems, the EU’s development cooperation funds, such as the EU trust funds, have been channelled toward migration-related projects across West Africa. In Nigeria, EU development funds have gone into training, capacity building, equipment, and awareness campaigns. A major reason for the focus of bilateral cooperation on migration for the EU is to tackle irregular migration to the EU. Meanwhile, other equally important contributing factors, such as reduction in trade, insecurity, low agriculture outputs, and other economic challenges, need equal attention in this new development cooperation focus. Instead, activities such as youth training programs and awareness campaigns supposedly linked to addressing the root cause of migration have become the focus for development corporations, with unclear outcomes on addressing these perceived root causes.

Stimulated political interest in migration

In discussing the impact of the EU’s involvement in Nigeria on migration, one cannot ignore the increased political interest of the Nigerian government as a result. Since 2015, the government’s interest in migration has further increased for the following reasons. First, there has been growing international pressure from development partners, especially from the EU and EU member states, for Nigeria to make migration a policy priority. In national debates, the topic gained prominence after the 2017 reports about the sale of African migrants by some criminal gangs in Libya. International actors have also used these events to legitimise further their focus on migration control vis-à-vis Nigerian state actors – highlighting their failure to respond adequately. Second, post-2015 EU development funding under the EUTF has been tied to migration management/governance, which requires the Nigerian government to react to migration issues. Third, the interest in migration has increased because of the prominent Nigerian diaspora community. For example, the Nigerian government realises the Nigerian diaspora’s substantial financial resources (in remittances and investments).

Harnessing these financial resources is vital for national development. Fourthly, the high number of IDPs and Nigerian refugees in Chad and Niger was a major political challenge for the Buhari government and will continue to be a challenge for the recently elected Tinubu government. Indeed, President Buhari campaigned heavily on defeating Boko Haram in his first term (2015 – 2019). Nevertheless, with the ongoing war and more Nigerians becoming displaced, the All Progressives Congress (APC) government cannot ignore these displaced people. From the above reasons, which account for the increased political awareness in Nigeria, it is fair to assess that pressure from the EU and other international partners turned out to be a “bitter-sweet” situation for Nigeria.

Hence, the government faced international and national backlash for its failure to curb the legal emigration of many Nigerians. Also, the flow of IDPs from the war in Northeast Nigeria constituted a political fiasco for the government, which campaigned to end the war in the first place. Additionally, the government used these years of migration (2015-2019) to strengthen its diaspora relations and institutional capacity to address migration challenges and set its agenda on labour migration.[16]

Improved migration legislation and engagement, albeit securitisation of migration

Nigeria’s decision to develop migration policies did not originate from the EU. For example, in 2003, the country enacted the Human Trafficking Act, which arose from the activism of the former Vice Lady Amina Abubakar Atiku. The Act subsequently established the National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking In Persons (NAPTIP) in 2003, making Nigeria the first country to criminalise human trafficking in Africa. The Trafficking Act was revised in 2005 and 2015 to protect minors and give stricter sentencing to culprits. Yet, the interest in anti-trafficking policies only translated into meaningful migration-specific-policy developments once the cooperation and partnership with the EU on migration gained momentum from 2010.

The Nigerian government’s increased interest in migration –resulting from EU policies and influence – has impacted migration policymaking in Nigeria. For example, Nigeria has comprehensive migration policies in addition to the ECOWAS migration protocols (see table 4).

The above table shows the adopted migration-specific policies that address the major migration patterns in Nigeria. It is hard to argue that Nigeria has policy gaps regarding migration with these policies. It is also true that the desire for migration policies originated from some national interests (for example, labour and diaspora) other than the EU’s involvement in Nigeria on migration after 2015. However, these policies were accelerated with EU funds and IOM technical support. Here, another area of impact of EU cooperation was the development of a coordinating framework. It follows the Swiss Whole of Government Approach that encourages inter-ministerial and multi-actor migration management. The coordinating framework brings together governmental, non-governmental, and international agencies and actors. The above-described policies and framework reflect that the involvement of the EU and its actors has resulted in policymaking on migration in Nigeria. The major challenge in Nigeria’s migration governance is implementing these policies (implementation gaps).

On another front, the involvement of the EU in migration management in Nigeria has led to rather securitised migration management. For instance, Nigeria enacted anti-smuggling policies and laws in the 1990s were in the context of human rights and security concerns. They linked trafficking to individuals’ economic survival and cultural practices. This has changed in recent years as trafficking is now linked to transnational networks of cartels and concentrated checking irregular migration to Europe –mainly in the interest of the EU.

Foreign Dominance and Domestic Rivalry

The Nigerian government is progressively showing political interest in illegalised migration and trafficking, return, and reintegration. Still, this interest does not correspond with the needed resources to address the issues. Budget allocations for key federal agencies have been fluctuating, showing a need for more consistency in sustaining the growing interest in migration with the needed funds. For example, in 2016, the government reduced the annual funding of NAPTIP from 2.5 billion Naira ($8.22 million) in 2015 to 1.69 billion Nairas ($5.56 million) (USDOS, 2017). Subsequently, the government allocated approximately 3.14 billion Nairas ($8.7 million) to NAPTIP in 2017, a significant increase from the 1.69 billion Nairas ($4.7 million) issued in 2016 (USDOS, 2018). Still, the overall budget allocated to migration agencies needs to be higher.

Meanwhile, the EU and EU member states fund the most initiatives on irregular migration, trafficking, return, and reintegration (see tables 2 & 3). Several EU member states like Germany, France, Denmark, and Switzerland also fund trafficking and irregular migration projects, support vocational and entrepreneurial skills training for returnees, and offer advice to potential migrants and returnees.

The National Commission for Refugees, Migrants, and Internally Displaced Persons N and NAPTIP are the statutory coordinating agencies for illegalised migration, trafficking, return, and reintegration in Nigeria. Nevertheless, due to inadequate resources by national actors, foreign organisations like the IOM, GIZ, and ICMPD, with substantial funding from EU and EU member states, have dominated migration projects and management in practice. This leads to ownership problems for Nigerian agencies that feel financially overshadowed by foreign organisations.

More so, the EU-Nigeria cooperation on migration has resulted in inter-agency rivalry at the federal and federal-state levels and amongst international organisations.

First, there exists a mandate-related rivalry between government agencies. For example, the National Immigration Service (NIS) considers itself better equipped to coordinate migration issues than the NCFRMI, established in 2009. The NIS is the oldest migration agency (established in 1963), with over 27,000 staff in 774 local governments and generates the largest volume of migration data. Additionally, the 2015 Immigration Act gives the NIS the power to prosecute people who break migration laws.

Second, there are disputes between some federal and state actors, such as between Edo State Taskforce Against Human Trafficking (ETAHT) and NAPTIP. On the one hand, the Taskforce seeks a broader mandate at the state level because of its capacity to deal with the issue of trafficking. NAPTIP, on the other hand, has the power to prosecute as a federal agency and will not tolerate any mandate of the Taskforce beyond investigating cases.

Third, there is an intense inter-organisation rivalry between leading international organisations, especially the IOM and UNHCR. At the UN level, the different mandates of these UN organisations are clear. However, in Nigeria, due to the enormous funding for IOM by funders like the EU, IOM is involved in almost all aspects of migration. These extensive roles of IOM leave less room for other international organisations like UNHCR, ILO, and ICMPD to operate. In the end, these disharmonies affect national actors. For example, in an interview with some NGOs and CSOs in Edo and Lagos, interlocutors mentioned that some foreign organisations would only choose to work with specific agencies, CSOs, or NGOs who do not have projects from their “rivals.”

These “powerful” institutions like IOM, UNHCR, ICMPD, GIZ and other EU member states’ development cooperation agencies have overshadowed NGOs and CSOs in migration governance but not in implementing grassroots projects. While the migration governance framework is unclear about the role of NGOs and CSOs, international organisations, the primary funding source for NGOs and CSOs projects, are significant backers of the framework. As a result, CSOs and NGOs, although very active at the community level, have yet to find functional space to play a role at the macro level.

Fragmented programmes between the federal and state level

Political stakes in irregular migration and human smuggling and trafficking differ between federal and state governments in Nigeria, leading to fragmented approaches to managing irregular migration. For example, using Edo and Lagos states, the political stakes on irregular migration differ from the federal government. In Edo state, issues of irregular migration are political and draw much societal attention compared to other states. Most EU and EU member states’ campaigns on irregular migration and return and reintegration projects are concentrated in the Edo state. Such campaigns focus on the dangers of irregular migration and neglect addressing the negative attitude against deportees. These campaigns fail to consider that the stigmatisation of deportation propels deportees to engage in a new cycle of irregular migration.

Lagos is a source and transit city for the many people trafficked to different destinations worldwide. It is also the “city of return” for the many Nigerians that are returned or deported from the EU and other parts of the world. Hence, successive Lagos state governments have prioritised job creation initiatives like the Lagos State Employment Trust Fund (LSETF). The Federal and State divide in Lagos is apparent when dealing with irregular migration and trafficking. National agencies like NAPTIP and NCFRMI take centre stage in close collaboration with IOM on these issues. This is not the case in Edo, where the State task force on trafficking is active and visible at the state level. Overall, the Nigerian government is yet to improve the smooth coordination of all programmes relating to migration in the country and support States’ initiatives that address their peculiar migration pattern challenges. This remains a challenge because of fragmented and uncoordinated donor funding.

Migration Statistics

Table 5: Migration Statistics – Nigeria[17]

18 UNDESA-Population Division and UNICEF. (2014). Migration Profiles.

19 United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2020). International Migration 2020 Highlights.

20 Eurostat. (2021). Asylum applicants by type of applicant, citizenship, age and sex – annual aggregated data (rounded).

21 See Oyekanmi, S. (2021). Nigeria attracts $9.22 billion in diaspora remittance in H1 2021, an increase of 16%.

22 World Bank Group. (2022). Personal transfer, receipt (Bop, current US$)- Nigeria.

23 Varrella, S. (2021). Number of international migrants in Nigeria in selected years from 1990 to 2020.

24 UNHCR (2022), Refugees and Asylum-Seekers in Nigeria as of May 31 2022.

Bibliography

Adelaja,A, Labo,A, & Penar, E. 2018. “Public Opinion on the Root Causes of Terrorism and Objectives of Terrorists: A Boko Haram Case Study.” Perspectives on Terrorism 12(3), 35-49. Retrieved from https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/binaries/content/assets/customsites/ perspectives-on-terrorism/2018/issue-3/03—public-opinion-on-the-root-causes-of-terrorism-and-objectives-of-terrorists-a-boko-haram-case-study.pdf.

Adepoju, A. 1996. “International migration in and from Africa: Dimensions, Challenges and Prospects.” Population, Human, Resources and Development in Africa (PHRDA), Dakar.

African News. 2019, August 13. “Nigerian students call for expulsion of South Africans. The Morning Call.” Retrieved from https://www.africanews.com/2019/08/13/nigerian-students-call-for-expulsion-of-south-africans-the-morning-call//.

Agbakwuru, J. 2018. “FG inaugurates Migration Centre in Edo.” https:// www.vanguardngr.com/2018/03/fg-inaugurates-migration-centre-edo.

Alqali, A. 2016. “Nigeria: When Aid Goes Missing.” IWPR. Retrieved May 21, 2019, from Institute for War and Peace Reporting website: https://iwpr.net/global-voices/nigeria-when-aid-goes-missing.

Aremu, J. O., & Ajayi, A. T. 2014. ”Expulsion of Nigerian Immigrant Community from Ghana in 1969: Causes and Impact.” Developing Country Studies 4(10): 176-186–186.

Assembly, G. 2000, November. Protocol onTrafficking.

Benattia, T., Armitano, F., & Robinson, H. 2015. “Irregular Migration Between West Africa, North Africa And The Mediterranean.” Retrieved from www.altaiconsulting.com.

Bergstresser, H. 2018. “Nigeria.” In J. Abbink, V. Adetula, A. Mehler, & H. Melber (Eds.), Africa Yearboob 14.

Black, R., Ammassari, S., Mouillesseaux, S., & Rajkotia, R. 2004. “Migration and Pro-Poor Policy in West Africa.” Brighton: Development Research Centre on Migration, Globalisation and Poverty

Brenner, Y., Forin, R., & Frouws, B. 2018. “The “Shift” to the Western Mediterranean Migration Route: Myth or Reality? ”. Mixed Migration Centre. https://doi.org/August 22, 2018.

Carling, J. 2005. “Traficking in Women from Nigeria to Europe.” Migration Policy Institute: 1–6.

Castillejo, C. 2017. “The EU Migration Partnership Framework Time for a Rethink?”. In Die. Retrieved from http://www.die-gdi.de.

Clemens, M. A. 2016. “Losing our minds? New research directions on skilled emigration and development.” International Journal of Manpower 37(7): 1227–1248. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-07-2015-0112.

Darkwah, S. A., & Verter, N. 2014. “Determinants of international migration: The nigerian experience.” Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis 62(2) : 321–327. https://doi.org/10.11118/actaun201462020321.

EASO (European Asylum Support Office). 2019. Country Guidance: Nigeria. https://doi.org/10.2847/096317.

European Commission. 2017. Partnership Framework on Migration – one year on. Fact Sheet, (June 2017). https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/factsheet_partnership_framework_on_ migration.pdf.

European Union. 2016. Nigeria: Action and Progress under the Migration Partnership Framework – June 2016 to June 2017. (June 2016), 2016–2018. Retrieved from https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/factsheet_work_under_partnership_framework_with_nigeria.pdf.

Flahaux, M. & De Haas, H. (2016). African migration: trends, patterns, drivers. Comparative Migration Studies (2016) 4:1. DOI 10.1186/s40878-015-0015-6.

Green, D.P., Wilke, A. and Cooper, J. 2018. “Silence Begets Violence: A mass media experiment to prevent violence against women in rural Uganda.” Working paper.

Gbandi, K., & Komolafe, V. 2019. “Communiqué of the 2nd Nigerian Global Diaspora Conference April 2019, Almere, Netherlands.” The African Courier. Retrieved from https://www.theafricancourier.de/africa/communique-of-the-2nd-nigerian-global-diaspora-conference-april-2019-almere-netherlands/%0D.

Haas, H. de. 2006. “Migration, remittances and regional development in Southern Morocco” Geoforum 37, 565–580. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=b496db13e67e1fd81c0689e2191d94b8989dda05.

Haas, H. de. 2011. “Irregular Migration from West Africa to the Maghreb and the European Union: An Overview of Recent Trends”. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37(32): 522–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2010.512208.

Hoffmann, C. 2018. “Die Stadt der Rueckkehrer.” https://www.tagesschau.de/ ausland/benin-city-rueckkehrer-101.html.

Home Office, UK. 2017. Country Policy and Information Note Nigeria: Boko Haram. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/778715/Nigeria_-_BH_-_v3_-_January_2019.pdf.

HRW (Human Rights Watch). 2017. “ They Forced Us Onto Trucks Like Animals .” https://doi.org/978-1-6231-35201.

Ikwuyatum, G. O. 2016.” The Pattern and Characteristics of Inter and Intra Regional Migration in Nigeria.” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 6(7) : 114–124.

IOM (International Organization for Migration). 2017. Migration Flows to Europe 2017 Overview: 1–13. Retrieved from https://reliefweb.int/report/world/migration-flows-europe-2017-overview.

IOM (International Organization for Migration). 2019a . Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration. Retrieved September 11, 2019, from International Organization for Migration, Nigeria website: https://nigeria.iom.int/programmes/assisted-voluntary-return-and-reintegration.

IOM (International Organization for Migration). 2019b. Traditional and Religious Leaders Join Forces to Curb Irregular Migration. Retrieved July 7, 2019, from Regional Office for West and Central Africa website: https://rodakar.iom.int/news/traditional-and-religious-leaders-join-forces-curb-irregular-migration.

IOM MENA. 2015. Migration trends across the Mediterranean: connecting the dots. Migration Policy Practice IOM, (June).

Kazeem, Y. 2017. “Nigeria’s first ever diaspora bond has raised $300 million.” Quartz Africa. Retrieved from https://qz.com/africa/1014533/nigeria-has-raised-300-million-from-its-first-ever-diaspora-bond/.

Kola, T. 2018. “You are on your own, Buhari tells Nigerian irregular migrants.” Retrieved July 11, 2019, from The African courier website: https://www.theafricancourier.de/migration/you-are-on-your-own-buhari-tells-nigerian-irregular-migrants/.

Luyten, K. 2019.”Legal migration to the EU.” Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2019/635559/EPRS_BRI(2019)635559_EN.pdf.

Mantzikos, I., Adibe, J., Onuoha, F., Solomon, H., Baken, D. N., Salaam, A., … Siegle, J. 2013. “Boko Haram: Anatomy of a Crisis.” In M. Ioannis (Ed.), e-International Relations. Retrieved from https://www.e-ir.info/wp-content/uploads/Boko-Haram-e-IR.pdf.

Marchand, K., Langley, S., & Siegel, M. 2015. “ Diaspora Engagement in Development: An Analysis of the Engagement of the Nigerian Diaspora in Germany and the Potentials for Cooperation. ”

Mberu, U. B., & Pongou, R. 2010. “Nigeria : Multiple Forms of Mobility in Africa ’ s Demographic Giant. ” Migration Policy Institute (June 2010): 1–22.

NAN (News Agency of Nigeria). 2018, December 6. “Nigeria contributes $710m to ECOWAS, more than 13 countries put together.” Premium Times. Retrieved from https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/299453-nigeria-contributes-710m-to-ecowas-more-than-13-countries-put-together.html.

Newdawn, N. 2019, January 19. “Nigerians disgrace Atiku, Saraki at Town hall meeting in U.S – New Dawn Nigeria. Newdawn Newpaper, Nigeria.

News24. 2018, July 7. “Buhari says Boko Haram-hit NE Nigeria now “post-conflict.” News24. Retrieved from https://www.news24.com/Africa/News/buhari-says-boko-haram-hit-ne-nigeria-now-post-conflict-20180706.

Nkala, O. 2015. “Germany To Broaden Scope of Support for Nigerian Army.” Retrieved September 23, 2019, from Defence News website: https://www.defensenews.com/land/2015/11/20/germany-to-broaden-scope-of-support-for-nigerian-army/.

O’Grady, S. 2018. “Nigerian Migrants Get a Welcome Home. Jobs Are An- other Story.” https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01//world/africa/migrants-nigeria- libya.html.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2019. Migration Data Brief 5: Are the characteristics and scope of African migration outside of the continent changing? https://doi.org/10.0%.

Olaiya, T. A., & Chukwuemeka, E. B. 2019. “Programme Migration for Development (PMD) Migration and Reintegration Advice in Nigeria.” Retrieved from www.giz.de

Orji, S. 2018, July 4.” Boko Haram, IDP returns and political calculations in Nigeria. Why are IDPs being urged to return to unsafe areas in Nigeria’s northeast? “.Aljazeera News. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/boko-haram-idp-returns-political-calculations-nigeria-180704135508696.html.

Osezua, C. O. 2016. “Gender Issues in Human trafficking in Edo State, Nigeria.” Revue Africaine de Sociologie 20(1): 36–66. https://doi.org/10.2307/90001845.

Pascoal, R. 2018. “Stranded: The new trendsetters of the Nigerian human trafficking criminal networks for sexual purposes.”

Paul, C., & Ahmed, K. 2018. “As Nigeria elections loom, refugees ordered back to unsafe region.” Reuters. Retrieved May 21, 2019, from Reuters website: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-nigeria-security/as-nigeria-elections-loom-refugees-ordered-back-to-unsafe-region-idUSKCN1LE18K.

Plambech, S. 2017. “Sex, Deportation and Rescue: Economies of Migration among Nigerian Sex Workers.” Feminist Economics 23(3): 134–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2016.1181272.

Policy Development Facility. 2017. “Nigeria Diaspora Study: Opportunities for Increasing the Development Impact of Nigeria’s Diaspora.” Retrieved from https://www.pdfnigeria.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Nigeria-Diaspora-Study-Final-Report-2.pdf.

Sharkdam, W., Akinkuotu, O., & Ibonye, V. 2014. ”The Nigerian Diaspora And National Development: Contributions, Challenges, And Lessons From Other Countries.” Kritika Kultura 23: 292–342. https://doi.org/10.13185/KK2014.02318.

Shoaps, L. L. 2013. “Room for Improvement: Palermo Protocol and the Trafficking Victims Protection Act.” Lewis & Clark Law Review 17: 931–972.

Süß, J. 2019. “Can the European Union deliver feasible options for legal migration? Contradictions between rhetoric, limited competence and national interests.” https://doi.org/SSN 2364-7043.

The African Courier. 2018.” You are on your own, Buhari tells Nigerian irregular migrants.” Retrieved September 5, 2019, from Migration website: https://www.theafricancourier.de/migration/you-are-on-your-own-buhari-tells-nigerian-irregular-migrants/.

Udo, R. K. 1975. “Migrant tenant farmers of Nigeria: a geographical study of rural migrations in Nigeria”. African University Press, Lagos.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). 2018. End of visit statement, Nigeria by Maria Grazia Giammarinaro. Retrieved May 16, 2019, from Statement website: https://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=23526&LangID=E.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). 2019a. Nigeria Situation. Retrieved June 30, 2019, from Operational Portal website: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/nigeriasituation#_ga=2.72954389.74165055.1561847052-1572706767.1549380893.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). 2019b. Operational Portal – Nigeria.

UN (United Nations) . 2000. “United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime.” Trends in Organized Crime 5(4): 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-000-1044-5.

UNDESA (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs). 2015. Trends in International stocks: The 2015 Revision. United Nations database, POP/DB/MIG/Stock/Rev.2015

Urowayini, W. 2018, June 17. “Boko Haram: 2000 IDPs return to Guzamala LGA to celebrate Eid-el-Fitr 6 years after – Army”. The Vanguard. Retrieved from https://www.vanguardngr.com/2018/06/boko-haram-2000-idps-return-guzamala-lga-celebrate-eid-el-fitr-6-years-army/.

USDOS (United States Department of State). 2018. 2018 Trafficking in Persons Report – Nigeria Publisher. Retrieved from https://www.refworld.org/docid/5b3e0ab6a.html.

Wapmuk, S., Akinkuotu, O., & Ibonye, V. (2014). The Nigerian diaspora and national development: Contributions, challenges, and lessons from other countries. Lagos: Nigerian Institute of International Affairs. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265569685_The_Nigerian_Diaspora_and_National_Development_Contributions_Challenges_and_Lessons_from_other_Countries.

Whitaker, B. E. 2017.” Migration within Africa and Beyond.” African Studies Review 60(2): 209–220. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2017.49.

World Bank. 2019. Migration and Development Brief : Migration and remittances recent developments and outlook. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2013.785721.

Footnotes

-

This paper is based on the research project ‘The Political Economy of West African Migration Governance (WAMiG)‘ and the subsequent report titled “The Political Economy of Migration Governance in Nigeria”. The paper is an updated version of the report mentioned above.

↩ -

Conflict-induced displacement as of 2021.

↩ -

Refugees population in Chad, Niger and Cameroon as of January 2023.

↩ -

Gubernatorial elections are scheduled for March 11, 2023.

↩ -

Colonisation in Nigeria occurred between 1900 and 1960 when the country gained independence from the United Kingdom.

↩ -

This number is without refugees and asylum seekers.

↩ -

Although the Nigerian diaspora in this section refers mainly to regular migrants, it should be observed that irregular migrants and persons connected to Nigeria through the transatlantic slave trade who consider Nigeria as their fatherland can also be regarded as part of the larger Nigerian diaspora.

↩ -

Racial capitalism is the process of deriving social and economic value from the racial identity of another person. See Nancy Leong’s article on Racial Capitalism in the Harvard Law Review Vol. 126, No. 8 (JUNE 2013), pp. 2151-2226.

↩ -

The concept of highly skilled and low-skill migrants is debatable without a singular agreed-upon definition. Adopting the OECD definition, a highly skilled is an individual with a university degree or extensive/ equivalent experience in a given field (OECD, 1998).

↩ -

See the National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP) database and Country Profile 2014.

↩ -

Established by the Lake Chad Basin Commission in 1998 to fight highway banditry and other cross-border crime. The current MNJTF is made up of troops from Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, Chad and Benin and has its headquarters in N’Djamena, Chad.

↩ -

Source: Interview with UNHCR official in Abuja (April 2019).

↩ -

Source: an interview with an official from the Nigerian Ministry of Labour and Employment (March 2019).

↩ -

Digital Explorers is a knowledge exchange initiative between the Lithuanian and Nigerian ICT markets, offering an opportunity for creating connections in the ICT sectors. It aims to fill vacancies in Lithuanian technology companies with Nigerian ICT talent. ICMPD initiated it on behalf of the European Commission.

↩ -

See “Mapping Of The Interlinkages Between Climate Change, Conflict, Fragility, Displacement And Migration In The Sahel And Horn Of Africa Regions [Tender Documents : T449493494].” MENA Report, Albawaba (London) Ltd., Dec. 2019.

↩ -

Read more on pages 19 & 20 of the original 2019 report.

↩ -

Read more from the original report here.

↩