Sahel

Published April 15th, 2022 - written by: Ekaterina Golovko

Please find a pdf version of this wiki entry here.

Imaginaries, Mobility, and Interventions

This report focuses on mobility in the Sahel and international political and humanitarian interventions related to mobility taking place there. In the last years, the Sahel became a key focus area of geopolitical interests. As a consequence, the Sahel increasingly became a space of international interventions.[1]To legitimize them, Sahel was framed as a space of ‘crisis and insecurity’, of ‘migration’ and of ‘intervention’. Each of these labels gives rise to different ways of dealing with the Sahel at the policy level and mutually constitutes the ‘identity’ of the Sahel, including the type of intervention taking place there. Considering the focus on the ongoing interventions, the present report will focus on the area of the Sahel denominated ‘Central Sahel’ embracing the Sahelian territories of Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali.

While policy interventions bear their own imaginaries of socio-spatial organizations, which often center around social fixity, this report aims to move beyond these neat categories and explore the ‘Sahel’ as a more fluid, social, spatial, political and historical space. This report analyzes the Sahel as a space conceptualized through movement and migration as a ‘mobile space’.[2] This definition understands the Sahel both as a space of human mobility, as well as a space that does not have clear-cut boundaries and various definitions. The fundamental question addressed in the report is how the Sahel can be defined through mobility and what possible spatial imageries derive from this? How could these imageries nurture policy approaches to migration in the Sahel?

The aim of the report is to get a picture of the recent developments related to mobility in the Sahel. In order to cover the different fundamental aspects of the political economy of Sahelian mobility, the report is structured as follows; the first section is dedicated to a variety of possible definitions of the Sahel: geographical, climatological, historical, administrative etc. The second section is focused on patterns of migration in the Sahel such as regional, seasonal and circular migration. The most common migration patterns that define the region are described in this subsection to illustrate a close connection and interdependence between livelihoods and migration. The third section is dedicated to the idea of the Sahel as a space of crisis based on the history of droughts and natural disasters, as well as the current multidimensional humanitarian crisis. The discursive and political definition of the Sahel as a space of ‘migration crisis’ is a consequence of the discursive and political creation of the European ‘refugee crisis’ of 2015. The creation of the EUTF (EU Emergency Trust Fund) and the narratives behind the political choices are examined in this subsection. The final section is focused on the externalization of the EU borders and the Sahel as a space of intervention. This section looks closely at some responses to the migration crisis in the Sahel, for example, the construction of the evidence base, i.e. data on migration that is used for the policy response, the reinforcement of the border management as a way to tackle transnational crime and ‘irregular’ migration; widespread use of returns as a type of assistance to stranded migrants.

Sahel as a geographical / political / imaginary space

‘The Sahel’ at the present moment has been framed as a region, as an idea, a space, a policy area and an area of study. Different approaches - spatial, geographical, political or historical – use different definitions. In any case, the Sahel’s identity is inherently related to the historical developments and political transformations in West Africa that occurred during the past centuries. As writes Alisa Lagamma, political transformations and historical developments are also partly “the stuff of legend, places whose stories remain vivid in the imaginative retellings of a living West African epic tradition’ contributing to the intersection of oral and written culture”.[3] More recently, the “Sahel” has become a generic name for the spatial construct comprising the Sahel-Sahara. The expanded definition of the Sahel includes now the Saharan zone, as well as a reformulation of the area’s characteristics. Very often the Sahel is associated with individual or collective shortcomings of the Sahelian countries in terms of security, governance, and monitoring of territory and borders.[4] In recent years, it is seen as an epicenter of violence, as a policy priority and as a center of neocolonial intervention by international actors.

This section is dedicated to different existing definitions of the Sahel and its multiple conceptualizations, from geographical definition to bioclimatic and administrative based on traced boundaries. It also focuses on the role of the Sahara desert for the conceptualization of the Sahelian space.

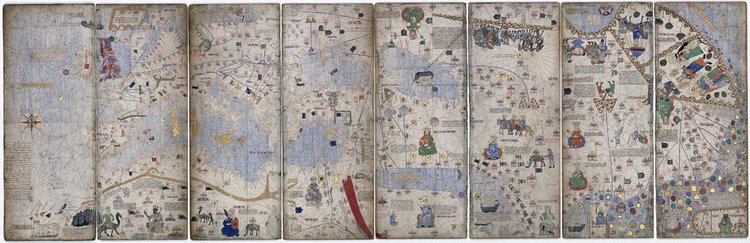

While speaking about the space, it is important to define from which point of view the space is seen. One of the most significant historical representations of the Sahara-Sahel region – seen from the outside – is the Catalan Atlas, created in 1375 by Abraham Cresques, a Majorcan map maker.[5]The Atlas consisted of the representation of the ‘known’ world and contained six folio vellum leaves folded vertically that were mounted on six wooden panels. The Atlas includes the representation of the African continent and features the Sahara Desert, shown with the common medieval mistake of a lake in its center. The map text beside a Tuareg riding a camel states that this land is inhabited by people who live in tents and ride camels. To the east of the Tuareg figure is Mansa Musa, King of Mali between 1312 and 1337, who encouraged the development of Islamic learning and whose kingdom was known for its substantial gold reserves. The map shows the relative predominance of Christianity vs. Islam by location, picturing crosses and onion domes, respectively.

This map had a significant impact on the way the Sahel, West Africa and the Sahara were imagined in the Middle Ages from the outside. It also shaped the representation of the region’s cultural identity particularly influenced by the tales of gold mining and narratives of wealth.[6]

Geographical definition of the Sahel

From a geographical point of view Sahel – from sahil ‘shore’ in Arabic –stands for the semiarid savanna zone stretching between the Sahara desert and the tropical savanna. The stretch between the Senegal and Niger River in West Africa is the first area that comes to mind when speaking of the Sahel.[7] Called in the Arabic manuscripts also a bilād as-sūdān - ‘land of Blacks’ – it also referred to as the divide between the desert and the savanna and also distinguished between North and West Africa or North and sub-Saharan Africa. This idea of the Sahel as a ‘shore of the desert’ discursively embodies the concept of ‘separation’, while in actuality the Sahel is a land of connections. Bilād as-sūdān incorporates both the idea of the desert’s two “shores,” with autochthonous “black” populations occupying lands below the northern sāḥil, alongside “nonblack” communities in territories above the southern sāḥil”.[8] The question of the utility of this binary and dichotomous representation of the space is also an important one, because it can be seen more productively as a borderland, as a liminal and transitional space “within which variegated communities and cultures were [and are] in mutual exchange over millennia”.[9]

Bioclimatic definition: Searching for the Sahel’s boundaries

While in the case of the Sahara desert a ‘shore’ is spatially quite a fluid concept. The desire to define the boundaries of the Sahel was also an important question for colonial scholars trying to fit the space into fixed boundaries. The neat separation between the Sahara and the Sahel was produced by the colonial geographers who wanted to divide and compartmentalize the space in order to make it ‘governable’ for the colonial administration. In an attempt to draw boundaries, the scholars searched for objective indicators. One such indicator, for example, is the level of rainfall, which was also interpreted as a line separating sedentary and nomadic ways of life. In this case, the equal amount of rainfall per location allows to draw isohyets, which are lines on a map connecting points having the same amount of rainfall in a given period. For instance, the 200 mm annual precipitation isohyet was defined as the cut-off for aridity, below which farming and herding were no longer possible. Regions receiving less than 200 mm of rain per year were considered Saharan while those receiving between 200 and 600 mm were considered Sahelian. Further south, the Sudanian domain was characterized by precipitation between 600 and 1300 mm, and the Guinean domain with precipitation greater than 1300 mm.[10]At the same time this distinction should also be seen as variable due to changing climatic conditions that are particularly strong in this area. Thus, any effort to use isohyets to define the boundaries of the Sahel proved challenging. Being a transitional zone between the Sahara and the Savannah, the variation of precipitation proved to be the highest in West Africa.[11] Observation of climatic conditions showed that rainfall anomalies are the norm rather than the exception and wet seasons can be followed by droughts in a rather unpredictable way. Isohyets thus do not represent fixed values and change over the years, making it impossible to draw a fixed line on the map. This impossibility fits into the Sahel’s description as a mobile space and also as a space of (human) mobility. The invention of a frontier between sedentary and nomadic lifestyles, as well as a line cutting off aridity proved to be an explicit example of use of presumably objective factors for the analysis.

Administrative definition: Tracing boundaries

Besides isohyets multiple possible grids for the organization of the space can also be used to frame the Sahel like national and administrative borders. The contemporary nations of Mali, Niger, Mauritania, Burkina Faso, and Senegal introduce an additional, quite recent, grid of subdivision of the space that does not coincide with bioclimatic lines. These fixed boundaries come as a result of a complex historical process of colonization and subsequent self-determination in 1960. Most parts of the West African Sahel between 1895 and 1960 were part of the Afrique Occidentale Française (AOF), or French West Africa.

The existing boundaries are also very often spaces of contention of the current political regimes. For instance, Liptako-Gourma, a tri-border area between Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso represents one of the epicenters of violence in the Central Sahel.[12] In Liptako-Gourma borders and borderlands are seen as transitional non-hierarchical, flexible and changing political environments. Liptako-Gourma has been framed as a ‘remote’ area in policy and academic papers because of the limited state presence as service and security provider and as border enforcer. This can be described as center-periphery deal-making where the state seeks to cede regions to insecurity rather than gain control it never actually had.[13]The remoteness of Liptako-Gourma seen from the center should also be negotiated looking at the region not from the capitals. The example of the abandonment and return of the security forces to the Labbezanga border post between Mali and Niger on the Gao-Niamey road axis is evocative. The post was abandoned in 2012; in November 2019, a deadly attack by affiliates of the Islamic State pushed the Malian army further away from the border, from Labbezanga to Ansongo, from Indelimane and Anderamboukane to Ménaka.[14] In May 2020, Malian Armed Forces returned to Labbezanga.[15] This suggests that Liptako-Gourma should not be framed from a state-centric position. At the same time, this so-called ‘remote’ area is actually an epicenter of negotiation of Sahelian power dynamics, the site of expression of existing tensions and political negotiations between ‘worlds’ metaphorically situated on the boundaries passing through Liptako-Gourma.

While the Sahara was studied and described by many scholars, both Arab and European, the image that is still wide-spread in policy environments can be reconducted to the ‘idea’ or a ‘fantasy’ of the Sahara rather than faithful and significant descriptions done through the centuries. The fantasy of the Sahara as a pristine space untouched by time, inevitably hostile to all but the most dauntless, has not disappeared. The idea of ‘empty’ space is still present in descriptions of the Sahara and Sahel; as Scheele and McDougall rightly define it, it is quintessentially the space of mystery, timelessness, and an eternal succession of catastrophes.[16]

The Sahel as a network

Growing archeological evidence confirms the understanding of the Sahara-Sahel as an interconnected region. It demonstrates that Sahelian links with North Africa existed before Muslim traders appeared, via the desert. in the late seventh to early eighth century, trans-Saharan trade increased significantly following North Africa’s integration into the Islamic world”.[17]

An alternative approach to represent the Sahara and the Sahel avoiding dichotomic visions or the idea of separation, is to adopt a relational view of the Sahel, to see it as a network, as a crossroads, as a space of connectivity. This imagery is illustratively explored in the work of Ursula Biemann.[18]Biemann’s video project Sahara Chronicle (2006-2009) works with the notion of geography both as a social practice and organizing system. This illustrates the modalities of migration across the Sahara through an open anthology of videos. It introduces the migration system as an arrangement of pivotal sites, each of which having a particular function in the striving for migratory autonomy, as well as in the attempts made by diverse authorities to contain and manage these movements.

SAHARA CHRONICLE BY URSULA BIEMANN from Ursula Biemann on Vimeo.

Historically, the Sahel has always been linked to the rest of the region, to the Sahara and to North Africa. A demonstration of this thesis is the history of the Sahel where a succession of empires was based on the control of the trade routes, marketplaces and cities.[19] While boundaries have the characteristic of separating, the routes instead connect places and create networks. In this case the reference becomes trans-Saharan routes, trade routes, cities and towns connected by these routes and roads, as well as people moving between these places. Connection and connectivity become key terms for the understanding of this land and its complex interrelations,[20], ethnic and kinship ties, rather than physical proximity, bound—and continue to bind —the cross-border trade networks together.[21] Movement is at the basis of space organization in the Sahara-Sahel. It was the key feature of the Sahel during the epoch of empires but also presently when connectivity and migration define and organize the space where nomads and sedentary groups remain in contact.

The interconnection and importance of flexible social networks that transcended national and climatic boundaries emerged when studies on pastoral, agricultural and trade movements of the Sahelo-Saharan populations became more prominent at the end of 1980s. These studies demonstrated that humanitarian crises had masked that local populations privileged movement over territorial fixity and the ability to circulate was primordial. Understanding the role of mobility helped to define the Sahel as a crossroads where space adapted to climatic variations and political crises.[22]

Approaching Sahara-Sahel through the lens of connectivity and movement, Scheele and McDougall suggest reconsidering the value of terms such as “local” and “regional”. They question whether one can exist without the other, especially in an area that is characterized by such a high degree of micro-regional specialization and hence large-scale, long-distance, and long-term patterns of connection and interdependence”.[23]

Informal trans-Saharan mobility represents a regional integration process beyond state control. It exists beyond regulatory frameworks and forms part of a spontaneous, worldwide movement among peripheral elements at different levels. Today, the revival of the ancient trans-Saharan routes forms the basis for a “grassroots integration” movement.”[24]

Sahel as a mobile space

Intra-regional mobility in the Sahel is overwhelmingly informal and difficult to quantify. Most of the Sahel (as it is conceived for this report) belongs to the ECOWAS, a free-movement zone.[25] Nonetheless obstacles to freedom of movements persist within ECOWAS. While the region experiences population movements due to conflict and insecurity (including forced displacement), most migratory movements fall within everyday life. For the majority of inhabitants of West Africa, migration is an important income diversification strategy for sustenance and a form of resilience to climate change, drought and desertification.[26] In the Sahel, the history of interdependence and interconnection of peoples is strictly related to trading and transhumance. The populations that are formally considered sedentary also rely on migration as an important source of their livelihoods. The common denominator for the area is ‘interdependence’, as a core feature of the movement across ethnic boundaries and economic specializations across the region.[27] This underlying structural factor continues to define the Sahel, albeit to varying degrees, notwithstanding intervening events and factors, such as colonialism and most recently, violent extremism and the so-called War on Terror.[28]

Migration also plays an important role in regional economies that engage not only those facilitating the movement of people across borders but also other sectors, including hotels, restaurants, businesses offering phone calls and mobile credit, internet access, food and water vendors, as well as the families receiving remittances or other forms of support. Migratory movements in the region are complex, often fragmented and non-linear, and migratory routes can change over time in response to environmental and contextual changes. However, regional migratory movements can broadly be classified based on their geographic extension (internal, cross-border, international movements), frequency (seasonal, circular or permanent migration) or objective (for study, work, family reasons, etc). An important distinction can also be made between rural-rural movements (mobility between rural areas, for example towards gold mines and agricultural sites, etc) and rural-urban migration (from rural to urban areas such as medium and big cities or capitals).

Rural-urban mobility: Africa remains predominantly rural. Yet over the past 65 years, its urban population has steadily increased, reaching 40.7% in 2019.[29] Movements towards capitals and large coastal cities attract migrants as places of wide economic possibilities, study and often also an obligatory stage in the fragmented migratory path towards other regions. Besides Bamako, Ouagadougou and Niamey, all other capitals in the ECOWAS region are located in coastal areas. Internal migration patterns to and from major African cities remain under-researched in comparison to migration dynamics to Europe.

Countries such as Mali and Niger experienced rapid growth in their urban population between 2000 and 2015 with urban growth rates at around 5%. It is estimated that by 2030, urban areas in Mali and Niger will welcome at least 400,000 and 190,000 additional residents each year, respectively.[30] The economic role of the capitals in countries like Niger, Mali, Senegal, Guinea and Burkina Faso is enormous. However, despite rapid population growth these capitals are marked by poor urban service delivery.

Seasonal and circular migration: Seasonal and circular migration: Seasonal migration within ECOWAS is related both to environmental factors and social traditions in West African and Sahelian societies. It is also a response to drought and desertification, natural disasters and a tool to diversify livelihoods.[31] Seasonal migrants most likely originate from Sahelian countries (such as Mali, Burkina, Niger, Chad and Sudan) facing food shortages due to recurrent drought. Serious droughts have affected the region in 1968, 1972, 1974, 1982 to 1985 and 2012, pushing people out of the region for temporary periods. The high level of dependence on subsistence agriculture causes many to diversify their livelihood activities in order to support their families, providing alternative income sources during lean times or periods of a lull in production, such as during the dry season. Migrants coming from rural areas reliant on crops tend to follow circular and cyclical migration patterns based on alternating seasons and activities. In many communities it is habitual to migrate to neighboring countries after the harvest, during the dry season and then to return home for the rainy season. For example, many young men go to gold mining sites flourishing now in Burkina Faso, Guinea, Senegal and Mali as a way to diversify incomes and earn additional money during the dry season. These incomes allow to accumulate money that can be invested in long-term projects such as marriage or business or similar. These migratory movements do not represent exceptional events but a normalized part of lifestyles and social fabrics. While migrants often lack state-issued documentation, they tend to enter the country easily due to the establishment of informal habits and relationships with those controlling the borders at checkpoints and along the route.[32]

Intra-regional mobility:Intra-regional mobility in West Africa and the Sahel was generally dominated by north-south movement from the landlocked West African countries of the Sahel strip (Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad) to plantations, mines and cities in more prosperous coastal West Africa (mainly Ivory Coast, Liberia, Ghana, Nigeria, Senegal and Gambia). The emerging economies of the Ghana-Ivory Coast migratory pole have attracted a large number of internal and international migrants, particularly from neighboring countries such as Togo and Nigeria (mainly to Ghana), Guinea (mainly to Ivory Coast) and Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali (to both).[33]

Migration between the Sahel and North Africa is also characterized by complex interdependence of the two areas, although apparently separated by the vast Sahara desert. In the 1960s, after the geopolitical reconfiguration of the region and independences of former colonies, countries like Algeria and Libya needed workers from the northern Sahel. Mobility from Mali and Niger to Algeria and Libya began to grow consisting mostly of seasonal migration related to agricultural work.[34]Libya and Niger signed an agreement in 1967 creating a legal framework as well as placing limits on migration, including those that were based on sectors (agricultural activities), space (the Saharan province of Fezzan) and time (seasonal).[35]

In the early 2000s close to 100,000 per year were passing through Agadez, one of the major transit points connecting the Sahel and North Africa.[36]Most of the migrants were traveling for longer periods of time and the number of migrant workers in Libya were estimated at 1.5 million, 300,000 in Mauritania, almost as many in Algeria, and tens of thousands in Tunisia and Morocco.[37]The level of connection and interdependence created by these migratory movements impacts the spatial organization of the region. For instance, due to development of the Saharan areas of Algeria and Libya the population and cities in the previously empty areas increased significantly. According to the OECD, the level of urbanization in the Saharan regions of Libya and in the Western Sahara has reached 90% and 95%, respectively.[35] At this point, migration and all connected social phenomena are an intrinsic part of the Sahara-Sahel area and cannot be forcibly halted.

As it is well known, before 2000 just a small portion of those traveling from West Africa and the Sahel intended to reach the EU. Since the early 2000s and specifically after the fall of the Gaddafi regime in Libya, a part of the interregional migration between the Sahel and North Africa became migration reaching the EU shores.

The Sahel as a space of crisis: migration crisis within a multidimensional crisis

Around 1960, West Africa and the Sahel, as already independent countries, started the process of decolonization which was widely seen as a new beginning and a new hope for the whole continent. Around the early 1970s the situation changed quite quickly due to dire climatological conditions. As Gregory Mann describes it: “Rains had failed for several years, and the huge herds of the 1950s and 1960s were dying for want of pasture.”[38] The Sahel became known around the world through media during the famine and droughts of 1973-74. The unprecedented humanitarian crisis was the cause of thousands leaving the Sahara-Sahel area in search of refuge and sustenance.[39] In the following decades rising temperatures and unpredictable extreme weather have caused prolonged droughts. Consequences were food shortages, desertification, heightened tensions between herders and farmers and abandonment by communities of locations where agriculture was no longer available.[40] Gregory Mann identifies this specific moment as a start of interventions - investment in food security and new forms of non-governmentality, - the spiral that has never stopped since then.[41] This moment also assigned the label of a ‘disaster zone’ to the Sahel.

The security situation deteriorated drastically due to the action of non-state armed groups and violent extremist groups. These developments have also caused an increased preoccupation with the mobility and transnational organized crime as threats to global security. From the academic or policy point of view, the Sahara-Sahel was framed as an interdependent region, a priority for the international actors.[42] This shifted the understanding of the area from a collection of states to a regional approach giving rise to a number of Sahel Strategies.[43]

Sahel as a space of multidimensional crisis

The humanitarian situation in the Sahel in the early 2020s continues to worsen, in particular due to expanding insecurity and growing number of attacks on civilians, both by insurgent groups as well as national and international military. From the humanitarian point of view the region finds itself in an emergency; the ongoing conflicts, jihadist attacks and governance failures all create extremely vulnerable conditions for the population that experience acute hunger and internal displacement. There is a dire need of humanitarian assistance in such domains as nutrition and food, health services, water and sanitation, shelter, education, protection, and support to survivors of gender-based violence. The proliferation of non-state armed actors exacerbates some of the predictable obstacles that restrict humanitarian access. These include but are not limited to: security and logistical barriers, decreased capacity of humanitarian actors, and the escalating challenge for aid organizations to navigate partnerships with regional and international stakeholders.[44]

Almost 7,000 people were killed in attacks in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger during 2020.[45] In Burkina Faso and Mali, more civilians were killed by local militias and national security forces than by attacks by Islamist armed groups.[46] According to MINUSMA, between June-December 2020 the Malian security forces were one of the leading perpetrators of extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions and enforced or involuntary disappearances. MINUSMA also reported that the security forces sometimes conducted “reprisal operations against civilian populations” accused of supporting Islamist groups.[45]

On their part, humanitarian organizations struggle to effectively provide for those in need. Six countries – Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Mali, Niger, Nigeria – have developed Response Plans for 2021, requiring a total US$ 3.7 billion.[47] Aid efforts are hindered by underfunding and the complex security environment.

The security situation in Mali has been deteriorating since 2012.[48] Nearly nine years after the onset of the crisis, the international community remains heavily focused on stabilization and counterterrorism, at times to the detriment of the worsening humanitarian situation.[49] In 2015, Islamist militants have regrouped and expanded into the central part of the country;[50] the violence has spilled into neighboring Burkina Faso and Niger, armed militias multiplied, including bandits, jihadists and self-defense groups.[51] Long-standing grievances between Dogon farmers and Fulani herders over land and resources have also increased considerably.[52] The Africa Center for Strategic Studies recorded an almost sevenfold increase in violent incidents connected to these groups in the Central Sahel since 2017, with a 44 percent increase in attacks in 2020.[53] In 2019, Burkina Faso suffered more jihadist attacks than any other Sahelian country.[54] Near-daily attacks by jihadist groups and local militias have forced hundreds of thousands more out of their homes and has caused the closure of hundreds of health centers around the country.[55] In 2020, the numbers of newly displaced people continue to increase, and hopes for an improved situation are bleak.

In 2019 across the three countries around 854,000 new internal displacements were recorded.[56][57] Burkina Faso revealed as the world’s fastest growing humanitarian crisis in 2019: between 2018 and 2020 the number of IDPs in Burkina Faso increased more than ten-fold to just over a million.[56] Such an increase is unprecedented and indicates a shift in the level of violence in the region, which is intensifying as a result of a multifaceted rural crisis. The displacement crisis in Burkina Faso has its roots in a complex set of factors including poverty, inequality and the increasing presence of violent extremist groups that have emerged partly as a result of the growing marginalization of certain population groups. Environmental degradation and climate variability are also drivers of vulnerability and displacement risk.[58] A similar trend continues in 2021. According to the UN, in July 2021, the displacement crisis in Burkina Faso shows no sign of slowing as attacks on civilians and security forces continue unabated.[59]

Armed groups attack not only civilian infrastructure such as health centers, education facilities but also IDPs. Armed groups have targeted IDPs in October 2020 when 25 were killed in an attack near the town of Pissila in the Centre-Nord region of Burkina Faso.[60] They have also attacked schools, disrupting children’s education, and triggered onward displacement among Malian refugees living in the north of Burkina Faso, where several thousands fled their camp in Goudoubo in the Sahel region in March 2020.[61] Access to health services and education has deteriorated, and IDPs are in urgent need of protection. There are more than twice as many displaced women as men, and many have been subjected to abuse and sexual violence. There are particular concerns about the protection of women in hard-to-reach areas where violence goes unchecked.[62] As a result, with the increase of insecurity, the humanitarian space shrinks, leaving less and less access possibilities for humanitarian actors to assist those in need.

Another source of crisis in the Sahel are natural disasters impacting livelihoods and displacement. In 2017 the government of Niger issued a decree that prohibits construction works in flood-prone areas, but construction in such areas continues and neighborhoods are repeatedly inundated during the rainy season, as it happened as well in 2020.[63]Flooding triggered more than 276,000 new displacements in 2020, many of them involving people who had already fled previous events in the same areas of the Tahoua, Tillabéri, Diffa and Maradi regions. The capital, Niamey, was also heavily affected when the Niger river broke its banks.[64] In Burkina Faso as well above-average seasonal rains in 2020 also caused widespread flooding across the country that destroyed more than 3,300 houses and triggered more than 20,000 displacements.[65]

Production of the Sahel as a space of migration crisis

Besides natural disasters and the multidimensional crisis, the region is also part of a more global construction of the so-called migration crisis. This image is constructed on a discursive level by mass media and political bodies. Since the 2015 European ‘refugee crisis’, the Sahel became the center of both the construction of a space of crisis, as well as the space of crisis response (this aspect will be discussed more in detail in the section dedicated to the externalization of the EU borders). In this specific case, the idea of a crisis was due to the increasing number of migrants arriving to European shores, through the Central Mediterranean Route (CMR) and the Eastern Mediterranean Route. A central part of the EU’s response to the increased arrivals through the EMR was the conclusion of the infamous EU-Turkey Deal. In an effort to externalize migration control along the CMR through cooperation with third states, European actors had to shift their cooperation further southward, from collaborating with the so-called Libyan Coast Guard to strengthening cooperation with the Nigerien government.

Discursively, through the creation of the EUTF and implementation of its projects as well as justification of the ongoing projects, the Sahel has been constructed as a space of crisis, specifically in the domain of migration. In policy documents the Sahel was often characterized as an ungoverned space with porous borders, lack of border control, presence of armed groups recruiting migrants (and radicalizing them).[66] While these statements are partially true, the constructed migration crisis deviates from the socio-political mobility realities within the region. Migration has been blurred with other transnational threats present in the Sahel, such as criminal networks and violent extremism. Such links and connections created an idea of the Sahel as a source of migration crisis, although the majority of migrants arriving to the EU do not originate from the Sahelian countries but just cross it, being most often from Senegal, Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea etc.[67]

In the following years, migration dynamics in West and Central Africa have been deeply affected by European migration management and security arrangements with the so-called Libyan coastguard. The European policy on migration in third countries - the so-called externalization of the European borders - aims to stop those traveling or intending to travel to the EU while they are still in countries defined as ‘transit’. This policy impacts all those involved in the migration economy, specifically those who do not intend to travel to the EU, that is the majority of those on the move.

Externalization of the EU borders: The Sahel as a space of intervention

The 2015 Valletta Summit was the response of the European political establishment to the ‘mass arrivals’ of irregular migrants on European shores. During the summit, the shared responsibility of countries of origin, transit and destination was stated. Since the Valletta summit, the implementation of anti-smuggling legislation in Niger, and other measures introduced (e.g. detention camps in Libya, EU Turkey deal, cutting down on and criminalizing SAR etc), migratory movements and arrivals to Europe by sea have been significantly reduced. One of the key outputs of EU’s migration policy on migration is the implementation of the law against human smuggling in Niger (law 2015/36). The impact of this law on migration in the region is significant.

The Valletta summit also led to the creation of the European Union Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF). It integrated the notion of ‘emergency’ into the migration vocabulary. This has blurred the lines between ‘humanitarian’, ‘development’ and political issues and reoriented as well the activities of IOs, INGOs, and other actors involved in migration management. As a consequence, several ad-hoc humanitarian protection programs for people on the move, articulated along the major migration routes have been initiated. In this context, foreign donors urge Sahelian states to adopt stricter monitoring measures and meet specific standards in border and migration management,[68] that is to adopt measures which are not consistent with national political agendas.

This approach to migration was denominated as the ‘externalization of European borders’.[69] It includes relocation of border controls to third countries, as well as the transfer of responsibility in the area of asylum, through which the EU aims at shifting to so-called “origin” or “transit” countries the responsibilities that Member States have internationally contracted since the 1951 Geneva Convention.[70] Besides increased border controls and management, the return of migrants from the countries of transit[71] prior to the arrival to the EU has become a significant part of migration management. From the creation of the EUTF, the EU’s capacity to “address root causes of irregular migration” was directly linked to its ‘capacity’ to control migration, i.e. more checkpoints, more controls and surveillance over migration resulted in more abuses and more protection incidents for migrants.[72]

Being an important migration transit area lacking allegedly ‘appropriate’ border management procedures that prevent transnational crime and ‘irregular’ migration, the Sahel became an area of massive intervention on migration. The structuring logic of this intervention is in line with the pre-existing idea that 'fixing' people in their countries of origin would create development perspectives and would improve overall conditions. In order to do so, the number of those migrating should be reduced and those in transit returned to the countries of origin. In the literature such an approach to development was criticized as having a ‘sedentary bias’[73], sharing and applying a model of development which aims to achieve a better quality of life at ‘home’ rather than through migration. Such an approach to migration and development is a reflection of the colonial ‘development project’ that is still reflected in many of the new initiatives on migration and development.[74] In fact, the approach to migration that the EU operationalizes through EUTF is the construction of the ‘migration paradigm’,[75] in which long-standing mobility patterns are increasingly labeled as problematic, irregular, and linked to security objectives. Particular attention is given to the borders and borderlands as examples of ‘ungoverned’ territories that need both security and border management intervention in order to stop ‘flows’ of illicit goods and of people that endanger the security of the EU. The lack of border controls is directly linked to the increase of ‘irregular’ migration and criminal networks.[76] This representation of the situation in the region reflects the political narrative on the need of the fight against terrorism, traffickers, smugglers.[77]

The following section considers some specific projects implemented in the region. First of all, it looks at the way the 2015/36 Nigerien law has impacted mobility in the region. The following section draws attention to the migration data collection as a source of knowledge that supports migration management programs. Then, it analyzes border management in the Liptako-Gourma as a way to reinforce control over the borders and stop illicit movements. Finally, it discusses ‘voluntary’ returns as humanitarian assistance. Most measures aiming at keeping migrants and refugees out of Europe have been presented as necessary to save human lives from the hands of smugglers and traffickers (alike).[78]

Effects of the 2015/36 Nigerien law

Starting from the political crisis in Libya, growing insecurity and destabilization, Niger emerged as the main transit country for those traveling from West and Central Africa to North Africa and also those attempting to reach the EU via Libya. The constellation of internal and external events increased pressure on the Nigerian government to commit to a clampdown on migratory movement in its territory. This pressure was then translated into the law 2015-36, implemented in late 2016[79] (loi N° 2015-36 relative au trafic illicite de migrants).[80] Niger received the biggest proportion of EUTF funds (€229.9 million) in West Africa.[81]EUTF projects in Niger focused on Nigerien communities, migrants and refugees and had a variety of objectives ranging from economic development and job creation for local communities, to support for migrants and refugees, border reinforcement, and increasing judicial and policing capacities.[82] The funding received is also an indicator of interventions taking place in Niger.

While data on arrivals of refugees and migrants in Italy indicates that many passed through Niger, the numbers and migratory movements significantly changed over time.[83] In 2013, as many as 3,000 people per week were passing through Agadez and using travel facilitators to move toward Libya.[84]The International Organization for Migration (IOM) registered a total of 111,000 people incoming to Niger and 333,000 people outgoing in 2016, with as many as 170,000 migrants, mostly from West Africa, passing through Agadez.[85]As such, migratory movements to and from Libya from 2017 onwards consist mostly of established circular migration patterns, consisting overwhelmingly (around 90% in 2017–2019) of people from Niger going to and coming from Libya, with the highest number of north-bound movements consistently observed at the end of the rainy season, around September and October each year.[86]

Studies on the implementation of the law suggest that anti-smuggling measures have led to changes in migration routes in order to escape military controls; to their fragmentation;[87] to their fragmentation;[86] departing at night and transporting fewer migrants;[88] the merging of drug smuggling and human smuggling routes;[89] the professionalization of the migration business; former migrant smugglers entering the business of trafficking the drug Tramadol between Nigeria and Libya; and an overall negative impact on stability.[90] Other reported effects of the law include an upsurge of banditry linked to the loss of income-generating activities by many people previously involved legitimately in the migration business. Repressive measures against smuggling have also been linked to an increase in prices and bribes that migrants and refugees have to pay.[91] In 2017, the IOM also recorded a “marked increase” in the number of migrants abandoned in the desert and related deaths.[92]

Data collection

The[93] shared responsibility of countries of origin, transit and destination established during the Valletta summit means blurring the lines between traditional ‘humanitarian’, ‘development’ and political issues,” reorienting as well the activities of IOs, INGOs, and other actors involved in migration management. Among numerous projects, it seems appropriate to highlight the establishment of several data collection systems in West Africa to monitor migration, previously nonexistent practices of knowledge production. This attention to migration data illustrates the will to justify action in migration governance through seemingly neutral numbers. Although all interventions are technically aimed at reducing the number of people reaching European shores, this so-called evidence-based approach justifies and seemingly depoliticizes these actions.

The case of data on migration: data collection, migration monitoring and contrasting priorities

European efforts to tackle irregular migration in a systematic way from the onset were linked to the capacity to “address root causes of irregular migration” and as well to the ‘capacity’ to obtain an in-depth understanding of the migratory phenomenon. Therefore, international organizations and donors needed a more evidence-based comprehension of migration, rooted in empirical knowledge of the situation ‘on the ground’. Who were the people traveling? Why were they traveling? What were their destination countries? What were they looking for? To answer such questions, the organizations themselves had to establish data-gathering facilities because the countries did not possess this information, or it was unreliable.[94] The interest was sharpened by the security concerns related to the identity of irregular migrants and asylum seekers arriving in Europe.

In this context the International Organization for Migration (IOM) has launched a system called the Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM).[95] It provides primary data and information at the national and international levels. DTM focuses on four main components: mobility tracking; flow monitoring; registration and surveys. At the moment of writing, IOM has more than 30 Flow Monitoring Points (FMPs) in West and Central Africa. Another data collection system with a significant database and knowledge accumulated is owned by the Mixed Migration Center, affiliated to the Danish Refugee Council’s 4Mi.[96]

In West Africa, 4Mi collects data in three countries: Mali (Mopti, Gao, Timbuktu and Kayes), Niger (Niamey, Tillabéry, Diffa and Agadez) and Burkina Faso (Bobo Dioulasso, Dori and Kantchari) collecting in-depth data on the motivation, the demographic profiles, protection incidents and humanitarian needs of the refugees and migrants interviewed. These two data collection systems can be considered complementary and not mutually exclusive.

While neither DTM nor 4Mi can capture all the migrants on the move, DTM is more focused on “flow” monitoring and capturing quantitative variations of migrants passing through a specific monitoring point. 4Mi instead can capture a picture on the ground in a non-representative manner. Also, a substantial difference between the two is in the number of persons interviewed. 4Mi monitors interview a fixed number of migrants each month, independently of the increasing or decreasing migratory movement, while DTM attempts to capture the number of people passing through each monitoring point.

Diverging interests

During the pre-EUTF era, West African countries’ capacity to monitor migration was weak. This is not surprising and can be explained by two distinct reasons. First, the nature of mobility in the region does not allow observers to quantify all the movements that take place, much of them being informal. If not openly supported, this type of mobility is tolerated by officials also because it is enshrined in the idea of the ECOWAS as a free movement area. A complex interplay between ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ domains co-exist in West African societies and cannot be ignored while policies are formulated. If all migratory movements are taken into consideration, then all the countries can be considered countries of origin, of transit and of destination at the same time,[97]contrary to the schematic opposition between ‘transit’ and ‘origin’ countries done by many external actors. Therefore, mobility is not seen as an extraordinary fact that needs ‘management’ or ‘monitoring’. It is not considered to be a security threat but much more so a source of development, at the societal and institutional level.[98]

Second, in the pre-EUTF era the border infrastructure did not correspond to the EU or international standards. The borders in the Sahel were and still are very porous. Until recently, long stretches of borders in the Sahel were neither delimitated nor demarcated.[99] As a consequence, border controls are partial and cannot ‘embrace’ the entire border. The statistics on border crossings are done on paper and not in electronic format; they can be lost, damaged and not transmitted to the capital where centralized national statistics are produced. Lax border control could also be explained by the insufficient number of active border posts that could not be established because of security concerns and overall adverse conditions. Those that were active and working often lacked proper infrastructure. The EU established a causal relationship between lack of border enforcement, lack of quality data on migration and irregular migration. Thus, the response was focused on increased border management that would impact the capacity of people to move with no obstacles. EU money and technical assistance resulted in the construction of new border posts, the enhancement of some existing ones and the supply of necessary equipment.[100] The data management was supposed to be improved by the introduction of the electronic system of Migration Information and Data Analysis System (MIDAS) installed by IOM. In addition, until recently, many travelers were not in possession of identity documents but crossed borders by paying bribes to the police. While in some countries the lack of documents constitutes a reason for a push-back, it is still possible to travel paperless in West Africa. Thus, in order to intervene on migration, the EU perceived the need for evidence-based knowledge on the profile of people traveling.

Diverging interests mean diverging priorities and approaches to migration. The case of migration monitoring and data collection systems is an example of diverging interpretations of the situation and of divergent agendas of external actors and West African governments. While data collection on migration is of crucial importance for the Western donors in order to profile migrants and ‘address the root causes of irregular migration’, it is a priority to a very limited extent for West African governments. So, when reading statements on ‘insufficient data on migration’ or ‘lack of data on migration’ as a limitation to the successful outcome of many projects, we need to situate this claim within the framework of contrasting interpretations of the context and diverging interests of external and national actors.[101]

In fact, in West Africa migration is more often looked at from a development perspective, as one of the sources of income for the governments and for the populations. Indeed, remittances sent by Africans living abroad provide an important source of income for those remaining in Africa. In 2020, personal remittances constituted 10,5% of GDP for Senegal, 5,6% for Mali, 2,8% for Burkina Faso and 2,2% for Niger.[102] In fact, the predominant association of migration in West African countries is that of wellbeing, prosperity and survival coming from migrants who support their communities and families. The involvement of the diaspora has a significant impact on the development of the country. Moreover, in countries like Senegal and Mali, where diasporas have a growing role and implication in the internal affairs of the country, the National Assembly has deputies from the diaspora. This aspect is illustrative of the diverging perceptions of migration in West Africa and in the EU (for the change of priorities within the EU from the Cotonou to the Valletta summits[103]). As a matter of fact, an illustrative example of the influence of the European political agenda on West Africa can be considered the drastic change occurred in Niger.

Border management and state sovereignty in the Sahel

A[104] repressive way to respond to the porosity of borders, to the lack of controls and ‘uncontrolled’ migration has been financed by donors including the EU, which has enforced borders, built and refurbished border posts. A set of interventions intended to improve the capacities of border officials and physical infrastructures, and enhancing communication between different levels of actors is denominated ‘border management’. It includes activities ranging from the purchasing and sharing of material support to the maintenance and monitoring of physical and technological infrastructures of the border as well as engagement and joint project implementation among a variety of border professionals, including security forces, migration specialists, humanitarian workers, and officers from international organizations.[105]

IOM defines its Integrated Border Management (IBM) program as a practice that assesses and enhances border management mechanisms: strengthening operational and strategic capacities to foster stronger connections between migration control and law enforcement systems among Sahelian states.[106] In the domain of infrastructural support, the IOM’s programs led among others, to the re-establishment of five border posts in Mali[107] that would expectedly improve monitoring of cross-border mobility as well as the state’s presence at the borders, as a symbol of the state’s capacity to exercise control over the territory. Moreover, the posts are equipped with IOM’s MIDAS data gathering, collection, and sharing system.[108] Therefore, border control becomes a set of existing practices applied to the control and management of borders by a growing number of personnel working in this area, as well as an area of expertise.[109]

In international development discourse, border management is often seen as a set of technical norms, standards and regulations, where implementing actors have more of a managerial expertise than a political role. In fact, as reflected in the various projects currently implemented by the IOM in the Sahel,[110] a focus on infrastructure, techniques, training and efficiency of personnel take precedence over discourse that would highlight the political and civic dimensions of the border.[111] This approach crucially depoliticizes questions of national security and the capacity of the state to control and protect its own borders. Thus, discursive separation between the political and the technical displaces border control to a conceptually-hybrid area of technical expertise on a political and sovereign domain. In fact, as reflected by the various projects currently implemented in Niger, aspects of infrastructure, techniques, training and efficiency of personnel take precedence over a discourse that would highlight the political and civic dimensions of the border.[112] Finally, borders require managers and managerial expertise, hence, there is an on-going shift in the nature of authority that defines the way borders are governed.

In the Sahel, state and border authorities are often regarded as not meeting international standards in terms of adequate training, equipment and remuneration. For this reason, external actors such as the European Union emphasize the need to increase the capacity of border officials, including training focusing on the knowledge, skills, resources, structures, and processes of relevant government authorities.[113]

Through these cooperation initiatives, a plethora of actors provide remedial intervention to (indirectly) ensure the capacity of states to perform their sovereign duties. This technical approach to border management downplays important power dynamics between external actors and the state. On the one hand, it silences the question of the nature of the state and how the state should be organized, how it should operate, depriving governments of their own agency and ability to question existing norms. On the other hand, it raises the question of the roles that external actors play in “increasing the capacities” of beneficiary states. The aim of capacity building, in other words, clashes with the means that are used: donors and partner states help beneficiary states reinforce their sovereignty through technical support and skills training, but at the same time, they impose their own agendas, values, and norms (often assumed to be universal or shared) and thus undermining the principle of sovereignty.

This inconsistency can be explained by the nature of capacity-building, or development interventions more broadly, as assuming a temporal or developmental gap between interveners and assisted states, meaning that each state, after undertaking the necessary steps, can/should be able to “catch up”, and reach the internationally prevailing model of statehood. The perceived temporal and developmental distance between donors and recipient states thereby justifies Western donor guidance of their African partners. But considering the control that these interventions exert upon sovereign states, it is not a neutral relationship but rather an exploitative one; what Mark Duffield has called a ‘relationship of government’.[114] In the current political context, furthermore, the European states are not as much imposing a coherent set of governance principles, but rather experimenting with them.[115]

Border surveillance committees

Border populations in the Sahel have first-hand knowledge of border areas and local conflicts at the micro-level. Due to growing insecurity, limited access, and capacities of security forces to control the borders, border populations are frequently included in border management portfolios; this results in establishing dialogue with security forces and participating in border surveillance and information sharing with security forces. Local communities are expected to organize security watches and report any suspicious movements to the security forces. These projects, often carried out by non-governmental organizations, see border communities not exclusively as beneficiaries but also as actors involved in border surveillance activities. In order to do so, members of border monitoring committees are provided with mobile phones to warn the authorities of suspicious movements.[111] This involvement shifts the burden of border protection from those entrusted to do so (but apparently incapable) onto those who should be protected. The problematic implementation of these activities is exacerbated by a well-founded reluctance of border communities to collaborate with security forces and authorities, both out of mistrust but also out of fear of revenge by non-state armed actors. Very often, the cell phones distributed to inform security forces remain silent.[116] Building trust between communities and the state turns out to be a much more complicated task than just the provision of goods or development assistance.[117]

What arises from this process is a hybrid security order where the state delegates its duties to civilians and non-state actors while still trying to demonstrate its symbolic presence at the borders. In many ways, the state is left out of an ever-changing construction of power relations where non-state actors interact directly with the populations, trying to bridge the gap with the state. Border monitoring committees seen from this perspective represent the blurring of boundaries between security forces, state authorities and the general population. Such mechanisms illustrate the way different actors, operating from below (civil society organizations and NGOs) and from above (IOs), play a central role in border management in the Sahelian context.

Border management’s effects on statehood

In order to look more closely at how border management practices affect state sovereignty, Ferguson and Gupta’s reflections on state verticality and encompassment are useful as an analytical tool.[118] In this understanding of how the state is related to society, ‘verticality’ refers to a state’s central and pervasive position as an institution ‘above’ civil society, community and family; ‘encompassment’ refers to the idea of the state as located within an ever-widening series of circles that begins with family and local community and ends with the system of nation-states. From this perspective, capacity building is a governmentality technique that alters state verticality. As discussed above, capacity building imposes contradictory governance agendas.[119] Through such intervention, the state – which should occupy the highest position in the verticality – is superseded by international or regional organizations (EU or IOM for instance) who ‘build’ the capacity of the state to perform its duties. These actions blur the boundaries between international agendas and sovereign agendas.

The involvement of local populations in border management, from the same conceptual perspective, is an example of addressing failing state encompassment. Border surveillance committees address a state’s lack of encompassment caused by the state’s inability to assert its presence over the territory and police state borders, fueled by the emergence of new forms of authority and overt contestation of state presence in the areas most affected by violence.

The types of interventions used in border management cast doubt over what is the ultimate goal behind such programs. The means used seem to be at odds with the stated policy objective of reinforcing state capacity. While those physically protecting the borders are exclusively national border officials, everything around them is a product of postcolonial hybridity where relations and interactions between multiple actors extend in capillary ways, undercutting the foundations of state sovereignty in the process.

Voluntary returns and protection of migrants

Protection of migrants in the Sahel

In[120] humanitarian action, protection is understood as advocating for, supporting or undertaking activities that aim to obtain full respect, protect and fulfill the rights of all individuals in accordance with the letter and spirit of relevant bodies of law.[121] Protection to all affected and at-risk persons has to inform humanitarian decision making and response, and be central to preparedness efforts, as part of immediate and life-saving activities, and throughout the duration of humanitarian response and beyond.[122] Thus, humanitarian responses must be driven by the needs and perspectives of affected persons, with protection at its core.

Increasing levels of violence in the central Sahel create greater difficulty or even impossibility of access for aid organizations. In such circumstances identification of vulnerable migrants, those in need of psychosocial assistance or victims of trafficking become more and more complicated to carry out. It is also extremely difficult to identify migrants in need because of the actual travel conditions. In the transit hubs migrants are often housed by smugglers and do not exercise full freedom of movement. The difficulties are exacerbated by the repressive climate around migration and the fear of migrants to be stopped. To tackle the needs of migrants in transit, tailor-suited solutions were created based on assistance along the migration routes. This approach allows aid organizations to deliver services in the transit hubs, at the checkpoints, in the bus stations and other key locations for migrants.

Assistance as return

In the current humanitarian landscape in the Sahel, assistance besides delivering specific services to persons in need is very often conditional to returns. While return operations are escape routes from the situations, they do not offer solutions to the root causes that generated these situations. At the same time, migrants should have unconditional access and agency in their ability to choose desired solutions.[123]

Framed this way within a highly politicized agenda, the humanitarian component becomes on the one hand a salvation, but on the other hand a means to effectuate so-called voluntary return, disincentivizing and deterring northbound mobility. Such programs make people on the move choose between their basic needs and their will to continue their journey, having (very often) to exclude the possibility to ask for help. This strong perception by migrants of the political ‘backstage’ of the events, deprives humanitarian programs of their neutrality, impartiality and independence because they are guided by the political agenda of migration control.

The first such program to be launched in 2016 was the EU-IOM Joint Initiative for Migrant Protection and Reintegration with funding from the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF). Officially, the program is intended to save lives, protect and assist migrants along key migration routes in Africa. As it can be seen from the title, protection and reintegration are associated here. By combining return with reintegration, IOM intends to operate ‘for the benefit of all’: for receiving states (that want to keep migrants away), for sending states (in need of development) and for migrants themselves (who would allegedly benefit from a better situation in their home country). The major focus of the program is the assistance to returning migrants to help them restart their lives in their countries of origin through an integrated approach to reintegration that supports both migrants and their communities.[124]From the point of view of protection, the program aims at improving protection, providing direct assistance and enable the assisted voluntary return of migrants stranded along the migration routes.

Returns from Libya and Niger to West Africa emerged as a humanitarian intervention on mobility in North and West Africa after official support for search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean Sea decreased and almost came to a halt at the end of 2016.[125]

The assistance provided, as listed in the report is: nutrition assistance, job creation, information campaigns, food security related services, etc. For example, according to the EUTF annual report, in Mali 2.191.800 people have improved access to basic services and in Nigeria 560.800 basic social services have been delivered.[126]While there is a significant difference between needs of the populations in general and specific needs of people on the move, the programs seem to mix them up, trying to tackle assistance to migrants through development assistance. Besides that, following the ‘sedentary bias’, the idea of returning people to their homes is considered by those programmes as a start of development trajectory.

Another humanitarian program based on assistance to migrants along the route is Red Cross’s Action for Migrants: Route Based Assistance (AMiRA) program with a specific feedback system.[127]It was funded under DFID’s 2018-2020 Safety, Support and Solutions Phase II (SSS II) program focusing on the Central Mediterranean Route (CMR) which aimed to make migration safer and provide critical humanitarian support, resulting in fewer deaths and less suffering along the CMR. The AMiRA program aimed to facilitate the access to basic services and the respect of migrants’ rights along the migratory routes, through the provision of humanitarian assistance, psychosocial support, information-sharing as well as support to reintegration upon return. The specific feature of the program was establishment of Humanitarian Service Points along migratory trails in Senegal, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali.[128] With a much more specific humanitarian focus and also a different donor – DFID – the program still had the return of migrants as one of its major focuses.

While all humanitarian organizations frame their actions as not deterring or favoring migration, but as explicitly neutral, the question arises whether it is possible to perform neutral actions under such conditions? In the cases of the EU-IOM Joint Initiative and AMiRA programs, return is framed as one of the ‘basic services’ or needs that is requested by migrants, in accordance with the above-mentioned definition of protection oriented towards needs of affected populations.

Framing returns as needs of migrants is probably related to the inaccurate interpretation of migration journey as not voluntary as well as migration containment interests of donors. Besides, such interpretation may also be based on erroneous understanding of the role of smugglers and the so-called ‘business model of smugglers’ as one of the major reasons for departures.[26]

From May 2017 until the end of October 2020, the EU-IOM Joint Initiative supported the voluntary return of 61.632 migrants from Libya (30.658), Niger (27.294) and other countries of transit and destination, including Mali (2.501). In countries of origin in the region, the Joint Initiative provided assistance to 87.858 migrants upon arrival whose return was supported by the EUTF or other donors.[129] Three countries that received more than AVRR and VHR to West and Central Africa in 2017-2019 were Nigeria 17.800, Guinea 17.200 and Mali 16.000. In total, all 23 country offices covered by the IOM Regional Office for West and Central Africa assisted migrants to return.[130]

'Voluntary return' programs usually have a "reintegration component" for returnees. Indeed, the successful reintegration of these citizens into their local communities and labor markets is of interest to West African governments. However, the process has remained contested: how much reintegration support is needed? Who should be responsible for this process? Given that the EU channels support through IOM, national actors would like to become responsible for externally funded reintegration support. Civil society actors argue that reintegration of returnees can only happen with the help of local communities.

In her seminal article “Security, development, protection. The triptych of externalization migration policies in Niger”,[131] Florence Boyer describes migration governance as an attempt to stabilize populations through such techniques as securitization, development aid and humanitarian protection. Boyer defines these as ‘construction of a protection space’ that are all aimed at containing northbound migration. Boyer focuses on the example of the protection space in Niger for asylum seekers and refugees,[132] underlining that this approach is functional to the refugee settlement and providing them with permanent housing and access to vocational training[133], i.e. activities that may give hopes for long-term perspectives.

The years of implementation of programs of protection and assistance to migrants, have demonstrated that they influence the perception of humanitarian actors by migrants. It becomes clear that many migrants see humanitarian actors as directly interested in their returns. Migrants in fact might ‘exploit’ assistance for their sake, for instance use transit centers to recover from hard journeys before setting out again. “Our group arrived here shortly before the confinement and it's a good thing because the IOM is taking care of us completely. We are provided with accommodation, food, clothing and even pocket money.” In other cases, migrants may try to avoid contact with humanitarian actors, exactly because of the fear of conditionality of assistance provided. “We can also count on some NGOs such as the Red Cross who often treat us when we are injured but the problem is that they will want to send you back to your country afterwards”.

These specific aspects need to be critically evaluated by humanitarian actors who participate in migration programs in the Sahel because the framing of assistance as return undermines principles of humanitarian action. Humanitarian assistance can thus materialize as a disincentive for those who do not want to be sent back to their countries. Assistance conditional to return and strong perception by migrants of the political ‘backstage’ of the events, deprives humanitarian programs of their neutrality, impartiality and independence because they are guided by a political agenda. Furthermore, in general migration and development programs on the African continent often have a sedentary bias. Thus, the implicit objective of reducing the flow of international migration, especially to the industrialized world is indicated.[134] Taking part in such projects also means that humanitarian actors actively participate in mobility restrictions desired by Western donors in the region.

Conclusion

This report provides an overview of different imageries on the Sahel, considering specifically the lens of mobility and migration. In order to do so, the first section, dedicated to the different possible and existing conceptualizations of the Sahelian space, demonstrated different ideas about what the Sahel is. It goes from the colonial bioclimatic definition based on the separation of nomadic and sedentary communities, to the rigid idea of the Sahel as a collection of nation states with inherited colonial borders. Finally, it suggests to see the Sahel and Sahara as interconnected spaces organized as a network where connectivity is more important than domination over territory. This understanding of the Sahelian space is crucial also for the analysis of possible interventions and also the critique of existing interventions based on the sedentary way of life as a given. The way space is conceptualized is actually a crucial way to approach the region and to intervene in the region. As it was demonstrated, the idea of the Sahel as a mobile space, as a network would avoid programs with sedentary bias, as well as an understanding of borders as lines in the sand.

The following section made a short overview of policies and policies imaginaries of the Sahel as a space of crisis. This is the dominant current representation of the area based on the insecurity, emergency of non-state armed groups and high levels of criminality. Insecurity causes high levels of internal displacement, especially in Burkina Faso. On the discursive level, the current situation fuels the idea and representation of the Sahel as a space of migration crisis, conflating actually the security and displacement emergency and the ‘European migration crisis’. The creation of the EUTF and with it the linking of a migration to an ‘emergency’ has a significant impact on the programs that are carried out in the region, as it is described in the final section. This section makes a short overview of donor driven migration control initiatives with a specific focus on some selected activities such as data collection on migration, reinforced border management and voluntary returns of migrants from transit countries to their countries of origin.

Furthermore, this report illustrates the claim that contrasting perceptions of migration can produce contrasting political agendas. West African governments often have to accept policies and projects that do not necessarily respect their priorities. The discrepancy between what West African countries prioritize and the EU’s political agenda deprives governments of agency and decision-making on their own political agendas. The policy mismatch may also cause long-term negative effects. The examples are not lacking: the building of new border posts in Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso with poor effective output; numerous capacity-building projects that do not cease human rights abuses by the security forces; widespread corruption on the checkpoints and border crossings that impacts the real capacity of the states to monitor migration and to guarantee safety to their citizens. Moreover, it endangers the project of regional integration promoted by the ECOWAS.

Several years after the creation of EUTF and the Valletta Summit, it became increasingly clear that the external and internal political agendas on migration do not match one with each other. The EU needs to take into consideration what the real interests of their partners are and accept that imposing its own political agenda cannot be productive in the long-term. The style of collaboration with African countries should undergo substantial changes and leave room to real negotiation where the African countries would have their own independent voice and political agency.

Sources

acaps (Ed.) (2019): Conflict and displacement in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. Available online at https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/20190322_acaps_regional_briefing_note_mali_-_niger_-_burkina_faso.pdf, last checked 23 April 2022.

Adal, Laura; Shaw, Mark; Reitano, Tuesday (2014): Smuggled Futures: The dangerous path of the migrant from Africa to Europe. Ed. The Globe Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. Available online at https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/2014-crime-1.pdf, last checked 27 April 2022.

Alpes, Jill (2020): Emergency returns by IOM from Libya and Niger. A protection response or a source of protection concerns? Ed. Brot für die Welt und medico international. Available online at https://www.medico.de/fileadmin/user_upload/media/rueckkehr-studie-en.pdf, last checked 27 April 2022.

Altai Consulting; IOM (Ed.) (2015): Migration Trends Across the Mediterranean: Connecting the Dots. Available online at https://publications.iom.int/es/books/migration-trends-across-mediterranean-connecting-dots, last checked 25 April 2022.

Altai Consulting; UNHCR (Ed.) (2013): Mixed Migration: Libya at the Crossroads, UNHCR Report. Available online at http://www.refworld.org/pdfid/52b43f594.pdf, last checked 18 April 2022.

André, Clémentine (2020): Why more Data is needed to Unveil the True Scale of the Displacement Crises in Burkina Faso and Cameroon. Ed. Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. Available online at https://www.internal-displacement.org/expert-opinion/why-more-data-is-needed-to-unveil-the-true-scale-of-the-displacement-crises-in, last checked 23 April 2022.

Andrijasevic, Rutvica; Walters, William (2010): The International Organization for Migration and the International Government of Borders. In: Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (6), pp. 977–999. Available online at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1068/d1509, last checked 27 April 2022.

Aniche, Ernest Toochi; Moyo, Inocent; Nshimbi, Chris Changwe (2021): Borderlands in West Africa are ungoverned: why this is bad for security. In: The Conversation, 01.07.2021. Available online at https://theconversation.com/borderlands-in-west-africa-are-ungoverned-why-this-is-bad-for-security-161453, last checked 23 April 2022.

Bakewell, Oliver (2007): Keeping Them in Their Place: the ambivalent relationship between development and migration in Africa. Ed. International Migration Institute (8). Available online at https://www.migrationinstitute.org/publications/wp-08-07, last checked 17 April 2022.

Bakewell, Oliver (2008): 'Keeping Them in Their Place': The Ambivalent Relationship between Development and Migration in Africa. In: Third World Quaterly 29 (7), pp. 1341–1358. Available online at https://www.jstor.org/stable/20455113?seq=1, last checked 23 April 2022.

Bensaâd, Ali (2003): Agadez, carrefour migratoire sahélo-maghrébin. In: Revue européenne des migrations internationales 19 (1), pp. 7–28.